The

artistic expression of Arpana Caur is the distillate of a long period of struggle.

It is not only the struggle of a determined and talented literary mother and her

two daughters, one of whom met with a tragic end in Paris, but of the Indian people

to free themselves from colonial rule. This history of ding-dong battles, beginning

as peasant and tribal revolts almost as soon as the East India Company spread

its tentacles over the country in the late eighteenth century, carried on relentlessly

till India became independent in 1947. And naturally, it left an indelible stamp

on our culture and expression.

The history of peasant revolts made the folk

artist the natural ally of the national movement and of the post-colonial artist,

re-establishing contacts with a continuity of culture even colonial brutality

could not suppress, nor postmodernism obscure. But while it seemed a natural enough

alliance in hindsight, it was not an easy one to forge at the time. The British

and the Indian colonial elite encouraged both an imitative Victorian imagery married

to Indian epic literature, as well as the revival of imperial miniatures, and

stylised Ajanta figuration after failing to attract the Indian aesthetic elite

to follow the colonial programme.

Even after Independence, Nehru tried

to revive Gupta art, which has had a lasting influence on a number of our leading

contemporary artists. Recently, the revival of Ravi Varma's art and bazaar kitsch

by the neo-colonial elite in a globalising India gives us evidence of new threats.

That contemporary artists, including Arpana, have been able to avoid these diversions

is to their credit.

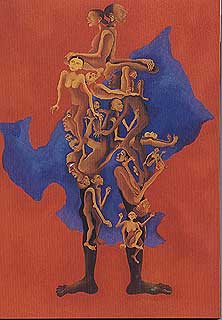

Arpana Caur went through this entire journey herself,

unlike other artists who were given readymade solutions at art school. Having

made a practical survey as it were, she chose definite options in her work from

1974 onwards. Her early figures remind one of the stocky, rounded treatment of

Gupta aesthetics, which she later blended with influences from Chola bronzes and

provincial Mughal styles of the Deccan and the Himalayan foothills. She then went

the whole hog into collaborative works with folk artists and ended up evolving

a visual expression that draws on folk motifs but expresses concrete present-day

concerns as a sort of 'magical reality'.

At every stage, she had to

make her own choice of visual language in relation to her own experiences, which

differ from the ordinary in many ways. She was born into a Sikh family of medical

practitioners who left Lahore during Partition and settled in Delhi in 1947. She

was brought up in a family of strong women, as her mother left a stifling middle-class

marriage to earn her living as a creative writer, with all the hardships it involved.

And finally, she faced the trauma of the Delhi riots in 1984, when Sikhs, who

regarded themselves as the sword-arm of India, and played a major role in its

struggle for independence, were slaughtered by politically motivated rabble after

the assassination of Indira Gandhi. All these events affected her life and art

profoundly.

The unconventional nature of the life she has led has helped Aparna

keep away from the conventional in art and strike out on a path of her own. That

is why she remained firmly figurative while most of Delhi' artists were steeped

in abstraction to one degree or another.

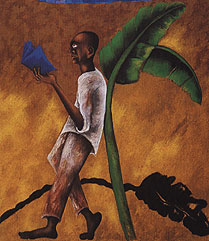

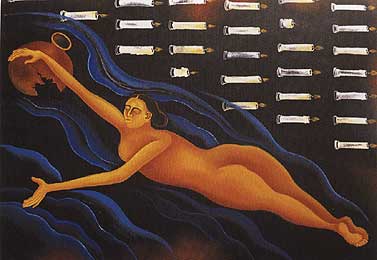

From

- Song of Water, 2000

The

incorporation of abstract and textured spaces in her compositions was a much later

development in keeping with her slow and steady progress based on her own perception

and experience. This is the basis of the authenticity of her art and its continuity.

Her

earliest works are those of an outsider looking at the colourful world of galleries

behind plate glass, but then there are works of the mid-' 70s that envisage the

breaking up of that window to 'let the outside in'. In fact, the inside-outside

theme predominates in her work of this period. She contrasts the drabness of one

sphere with the brightness of the other. What is interesting is that the duality

does not hold her down. Sometimes the inside is drab, sometimes the outside. She

is her own master.

This comes out much more forcefully in the first of her

original images: The Child Goddess. Here she portrays a nude girl lecturing

to several nude figures who are immersed in their own concerns and not listening

to her. They could well be statues. These images appear to contain the germ of

a future series in them: the one of a performer without an audience. They recur

again and again in different contexts in her works, growing in subtlety and sensitivity

over the years.

The blatantly disinterested crowd the child-goddess is addressing

becomes the audience whose absence is indicated in The Missing Audience series

of 1981, through empty chairs: and finally, people are pictured as visibly immersed

in petty day-to-day concerns, ignoring riot victims floating past or dead bodies

lying on the ground, in her series - World Goes On. This series, painted from

1984 onwards, reflects a growing sensitivity in her portrayal of reality.

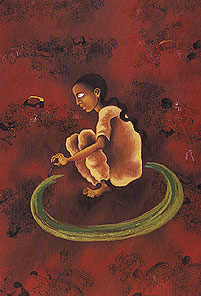

From

World Goes On series, 1984

The

audience in The Child-Goddess series, is stone deaf, but present. In The Performance

series, it is absent. Both these, however, do not capture indifference in all

its complexity as do the images of people living their daily lives, doing mundane

things, while riot victims float past them unobserved. This demands considerable

artistic depiction and reflects the real flowering of this image. The fact that

we are able to trace this image of the mid-'70s, evolving in different conditions

and emerging as a hard reality in the '80s, not only of present-day India, but

of a world being continually desensitised by a flood of information and making

a spectacle of everything, including appalling human tragedies, reflects how her

art is genuinely a product of the progress of her life and times and not borrowed

stuff.

The continuity of this image over decades, drawing different elements

into it and enriching it visually, reveals her to be very much an artist with

her own agenda. She is neither influenced easily nor given to chopping and

Working

on the Time

mural in Hamburg,

with Sonke Nissen,

2000

changing

her expression with what is fashionable at the time or to please the market forces.

She always has a message to give: this dictates the large size of her works, such

as a massive mural done in collaboration with a German artist, covering four storeys

of a five-storeyed building in Hamburg.

This monumentality, both of her themes

and their visual representations, gives her work the historicity of classical

artists, like the muralists of Ajanta. This is why a number of museums, like the

Victoria and Albert and the Bradford Museums in Britain, the Kunstmuseum in Dusseldorf,

Germany, the Hiroshima Museum of Modern Art and the Glenbarra Museum in Japan,

the Ethnographic Museum in Stockholm(Sweden), the Singapore Museum, the National

Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) and other museums in India, have chosen to acquire

her works. However this history is personalised with the artist as the centre

of her world which has the stampof comtemporaneity on it.

And yet, there is

nothing narrow about the way she visualises these themes, using time-tested images

in a new context. This helps her art to convey its freshness without sacrificing

its mainstream quality.

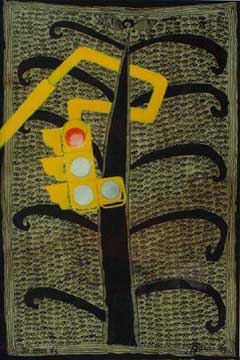

The tree, a prominent

feature of the Time Image series, 1990

Take,

for example, her use of the umbrella as a visual. In her earliest work it is a

protective device. Starting out as a distinguishing feature in images of women

who are protected and those who are not, in The Sheltered Women series, it takes

the form of a human being, in her mother and daughter images; of a banana leaf

in her Time Image series and in some of the images in her Resilient Green series,

or even a Guru Granth Sahib protecting her grandfather carrying his belongings

in a sack from Pakistan in her Partition series. There is a universality of discourse

in the images she uses but the context is personal.

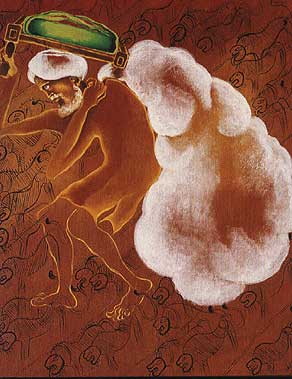

It is drawn from many different

sources. There are images from ritual, like the umbrella; from legends, like the

woman with scissors, reminiscent of the classical Greek myth of the Fates; the

upturned Kalpavriksha of Hindu mythology; or from the poetry of Nanak and

Kabir, as in The Body is Just a Garment series. Then there are physical images

of the Tirthankaras, the Buddha, Ghalib, Bhagat Singh, Udham Singh, and even the

popular image of Raj Kapoor and Nargis under an umbrella from the film Shri 420.

There is also the global image of a bombed-out public building of Hiroshima that

the nuclear threat posed by imperialism has given worldwide significance to, in

a work commissoned by the Hiroshima Museum for the fiftieth anniversary of the

holocoust. Lately, she has added images from the folk-art of the Warlis and of

tattoo artists of the Godna tradition to her repertoire.

But then she shifts

the focus of these to her personal contemporary view of things. There is nothing

reverential about it, as we can see from the figures of saints plugging in to

the Tree of Enlightenment, or of Khushwant Singh's Train to Pakistan cutting

across the dialogue of Bhagat Singh and Gandhi on violence and non-vio\ence. These

are personal statements, like her letters to Ghalib, that we fine tune into, after

the initial contact with existing and known images is made, giving them universal

relevance beyond mere authenticity.

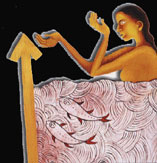

What really makes them stand out, however,

is her unselfconscious way of expressing these realities as she does in her goddesses

of the past and present, contrasting the devi figure with that of a female building-labourer

carrying bricks. Her art is remarkable in the simplicity with which she presents

a radical view of the realities of our lives, using images that we are used to,

in a new context. She confronts us with images of policemen firing at angels in

the sky; of trees as providing both shade and a butt for a gun;

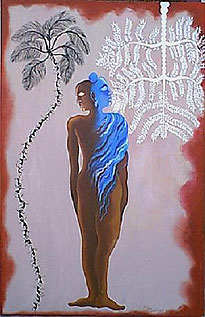

Night

and Day, 6' x 4', oil on canvas, 1998

of

neatly-lined kitchen knives; of houses burning; of widows with shaved heads drowning

in the Ganges; of forms that remind us of Renaissance art with cherubs in the

sky; of miniatures of satis; of popular ritual images of gods and goddesses; so

we are repelled, but not so much that we refuse to think of these things.

Structurally

she achieves this by confronting us with dualities: figurative and abstract, monochromatic

and polychromatic, the single image and its multiple reproductions, men and women,

day and night, land and water ... She is always alive to the fact that everything

has two sides to it. She could have left it at that. But she does not want to

sit on the fence safely. She takes sides, and with a very clear perspective of

a future where humanity confronts oppression; peace confronts war; and the environment,

pollution. Hers is an art of hope and of a sense of liberation on a grand scale.

And a world becoming smaller every day takes to it naturally.

(Article taken with thanks from 'The art of Arpana Caur, by Suneet Chopra with photos of paintings by Brig.D.J.Singh) We present more of her art below:-