William Osborne was A.D.C. to the Governor-Genera], Lord Auckland. During his stay in India he could spend some time in Maharaja Ranjit Singh's court and wrote an interesting record about the time he spent with him, shortly before he died. In his book, 'The Court and Camp of Runjeet Singh', he gives insights into Ranjit Singh's exceptional character Osborne first saw him "Crosslegged in a golden chair, dressed in simple white, wearing no ornaments but a single string of enormous pearls round the waist, and the celebrated Koh-i-nur, or mountain of light, on has arm - the jewel rivalled; if not surpassed, in brilliancy by the glance of fire which every now and then shot from his single eye as it wandered restlessly round the circle - sat the Lion of Lahore The more I see of Runjeet Singh, the more he strikes me as an extraordinary man. Cunning and distrustful himself, he has succeeded in inspiring his followers with a strong and devoted attachment to his person; with a quick talent at reading men's minds, he is equally adept at concealing his own; and it is curious to see the sort of quiet indifference with which he listens to the absurd reports of his own motives and actions which are daily poured into his ears at the Durbar, without giving any opinion of his own, and without rendering it possible to guess what his final decision on any subject will be, till the moment for action has arrived. Though he is by profession a Sikh, in religion he is in reality a sceptic, and it is difficult to say whether his superstition is real, or only a mask assumed to gratify and conciliate his people. He is mild and merciful as a ruler, but faithless and deceitful; perfectly uneducated, unable even to read or write, he has by his own natural and unassisted intellect raised himself from the situation of a private individual to that of a despotic monarch over a turbulent and powerful nation. By sheer force of mind, personal energy and courage (though at the commencement of his career he was feared and detested rather than loved), he has established his throne on a firmer foundation than that of any other eastern sovereign, and but for other watchful jealously of the British government, would long ere have added Scinde, if not Afghanistan, to his present kingdom. Ill-looking as he undoubtedly is, the countenance of Runjeet Sing cannot fail to strike everyone as that of a very extraordinary man; and though at first his appearance gives rise to a disagreeable feeling almost amounting to disgust, a second look shows so much intelligence, and the restless wandering of his single fiery eye excites so much interest, that you get accustomed to his plainness, and are forced to confess that there is no common degree of intellect and acuteness developed in his countenance."

Osborne also had the opportunity to record about Maharaja Ranjit Singh's lively banquets. "On my return home, I met the Maharajah taking his usual ride. He was very inquisitive as to where I had been, and I never saw him in so good a humour or such high spirits. After a good deal of gossip upon various subjects, he said, "You have never been at one of my drinking parties; it is bad work drinking now as the weather is so hot; but as soon as we have a good rainy day, we will have one." I sincerely hope it will not rain rat all during our stay, for, from all accounts, nothing can be such a nuisance as one of these parties. His wine is extracted from raisins, with a quantity of pearls ground to powder, and mixed with it, for no other reason (that I can hear) than to add to the expense of it. It is made for him alone, and though he sometimes gives a few bottles to some of his favourite chiefs, it is very difficult to be procured, even at the enormous price of one gold mohur for a small bottle. If is as strong as aquafortis, and as at his parties he always helps you himself, it is no easy matter to avoid excess. He generally, on these occasions, has two or three Hebes in the shape of the prettiest of his Cachemirian girls to attend upon himself and guests, and gives way to every species of licentious debauchery. He fell violently in love with one of these fair cup-bearers about two years ago, and actually married her, after parading her on a pillion before himself on horseback, through the camp and city, for two or three days, to the great disgust of all his people. The only food allowed to you at these drinking bouts are fat quails stuffed with all sorts of spices, and the only thing to allay your thirst, naturally consequent upon eating such heating food, is this abominable liquid fire. Runjeet himself laughs at our wines, and says that he drinks for excitement, and that the sooner that object is attained the better Of all the wines we brought with us as a present to him from the Governor-General, consisting of port, claret, hock, champagne, etc., the whiskey was the only thing he liked. During these potation" he generally orders the attendance of all his dancing girls, whom he forces to drink his wine, and when he thinks them sufficiently excited, uses all his power to set them by the ears, the result of which is a general action, in the course of which they tear one another almost to pieces. They pull one another's nose and earrings by main force, and sometimes even more serious accidents occur; Runjeet sitting by encouraging them with the greatest delight, and exclaiming to his guests, "Burra tomacha, burra tomacha" (great fun)."

Osborne was greatly impressed with Pratap Singh, the young son of Sher Singh, who even at a tender age once escorted him. "Pertaub Singh was handsomely dressed, armed with a small ornamented shield, sword, and matchlock, all in miniature, covered with jewels, and escorted by a small party of Sikh cavalry and some guns. His horse was naturally of a white colour, but dyed with henna to a deep scarlet. He is one of the most intelligent boys I ever met with, very good looking, with singularly large and expressive eyes. His manners are in the highest degree attractive, polished, and gentleman-like and totally free from all the mauvaise bonte and awkwardness generally found in European children of that age. He is young and a very interesting friend. He expressed his thanks in graceful terms on receiving my present of a gold watch and a chain, and on parting said "You may tell Lord Auckland that the British Government will always find a friend in the son of Sher Sing." Then, mounting his horse covered with plumes and jewels, he gracefully raised his hand to his forehead and galloped off with his escort, curvetting and caracoling round him in circles till he was out of sight." At that time he was only eight years of age! In Emily Eden's lithograph he indeed looks like a bright child. (see painting of Kunwar Partap Singh in part 1)

Two years later, introducing his journal which was published after Maharaja Ranjit Singh's death, he critically wrote about Maharaja Ranjit Singh: "Brought up but not educated in the idleness and debauchery of a zenana, by the pernicious influence of which it is marvellous that the stoutest mind should not be emasculated, he appears from the moment he assumed the reins of government to have evinced a vigour of understanding on which his habitual excesses, prematurely fatal as they proved to his bodily powers, produced no sensible effect. His was one of that order of minds which is destined by nature to win their way to distinction and achieve greatness. His courage was of that cool and calculating sort, which courted no unnecessary danger, and shunned none, which his purposes made it expedient to encounter; and he always observed a just proportion between his efforts and his objects. Gifted with an intuitive perception of character. and a comprehensive knowledge of human nature, it was by the overruling influence of a superior rnind, that he contrived gradually, almost insensibly, and with little resistance, not only to reduce the proud and high-spirited chiefs of his nation to the condition of subjects, but to render them the devoted adherents of his person, and the firm supporters of his throne. With an accurate and retentive memory, and with great fertility both of invention and resources, he was an excellent man of business without being able to write or even to read. As insensible to remorse and pity as indisposed to cruelty and the shedding of blood, he cared neither for the happiness or lives of others, except as far as either might be concerned in the obstruction or advancement of his projects, from the steady pursuit of which no consideration ever diverted him. His success, and especially the consolidation of his power, are in great measure attributable to the soundness of his views, and the practicable nature of his plans. He never exhausted his strength in wild and hazardous enterprises, but restraining his ambition within the limits of a reasonable probability they were not only so well timed and slulIfully arranged as generally to ensure success, but failure (in the rare instances when they did fail) never seriously shook his stability, or impaired his resources. He seems to have had a lively, fanciful, and ingenuous mind, but the ceremonious forrus of Indian etiquette and the figurative and hyperbolical style of Oriental intercourse, are not favourable to the development of social qualities. Runjeet, however, had a natural shrewdness, sprightliness and vivacity, worthy of a more civilized and intellectual state. He was a devout believer in the doctrines, and a punctual observer of the ceremonies of his religion. The Grunth, the sacred book of the Sikhs, was constantly read to him, and he must have been familiar with the moral precepts it inculcated. But nothing could be more different than the precepts of Nanak and the practices of Runjeet. By the former were enjoined devotion to God and peace towards men. The life of Runjeet was an incessant career of war and strife and he indulged without remorse or shame in sensualities of the most revolting description. Nor did the excesses over which he was at no pains to throw a decent veil either detract from his dignity or diminish the respect of his subjects; so depraved was the taste and so low the state of moral sentiment in the Punjab. It is no impeachment of the sagacity of Runjeet that he was a believer in omens and charms, in witchcraft and in spells. Such superstitions only prove that early impressions were not eradicated and that his mind did not make a miraculous spring beyond the bounds of his country and his age."

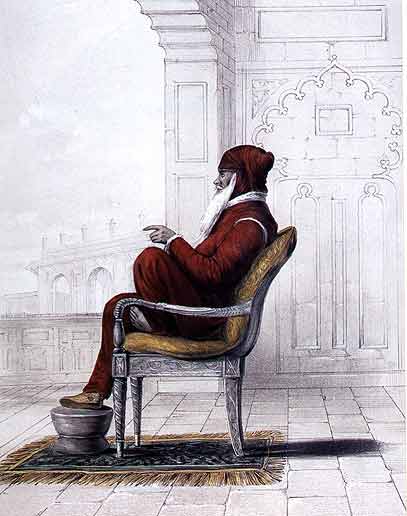

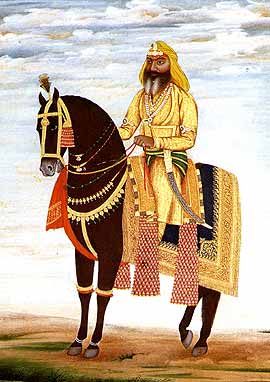

Baron HugeL an Austrian traveller, also visited Ranjit Singh's court during his later years, when he was partially paralysed. "I must call him the most ugly and unprepossessing man I saw throughout the Punjab. His left eye, which is quite closed, disfigures him less than the other, which is always rolling about, wide open, and is much distorted by disease. The scars of the smallpox on his face do not run into one another, but form so many dark pits in his greyish-brown skin, his short straight nose is swollen at the tip and his head, which is sunk every much on his broad shoulders, is too large for his height and does not seem to move easily. He has a thick muscular neck, thin arms and legs, the left foot and the left arm dropping, and small well-formed hands. He will sometimes hold a stranger's hand fast within his own for half an hour, and the nervous irritation of his mind is shown by the continued pressure on one's fingers. His Costume always contributes to increase his ugliness, being in winter the colour of gamboge. When he seats himself in a common English armchair, with his feet drawn under him, the position is one particularly unfavourable to him; but as soon as he mounts his horse, and with his black shield at his back, puts him on his mettle, his whole form seems animated by the spirit within, and assumes a certain grace, of which nobody could believe it Susceptible. In spite of the paralysis affecting one side, he manages his horse with the greatest ease. If nature has been niggardly to him in respect of personal appearance, she has recompensed him very richly by the power which he exercises over everyone who approaches him. He can in a moment take up a subject of conversation, follow it up closely by questions and answers, which convey other questions in themselves, and these are always so exactly to the purpose, that they put the understanding of his respondent to the teat. With a voice naturally rough and unpleasant, he can assume a tone of much fascination whenever he wishes to flatter; and his influence over the people of northern India amounts to something like enchantment."

Seeing them again when calling on Ranjit Singh some days later she bristled with irritation at their behaviour and that of their bibulous guardian: 'Those two little brats, in new dresses, were crawling about the floor, and he poured some of this fire down their throats'. Schoefft believed that they received half their fathers' income until they reached the age of fifteen, and if still alive after Ranjit Singh's questionable supervision beyond that age, they were entitled to the whole revenue. (Aijazuddin)."

With the collapse of Maharaja Ranjit Singh's kingdom, the art of traditional painting disappeared from Lahore and Amritsar but continued in the other British protected Sikh States like Patiala, Kapurthala, Nabha, Jind, Faridkot and smaller places like Una. In fact, with the peaceful conditions encountered by these states under the patronage of the British, indulgence in the arts and court leisure activities increased considerably. The Lahore court artists soon migrated there and evidence exists of artists reaching there directly from Delhi and even Rajasthan (the Hindu mythological paintings at Sheesh Mahal, Patiala, give it the air of a Hindu palace)

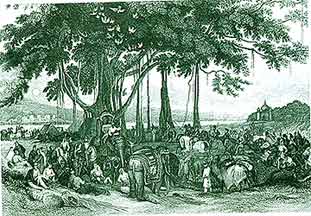

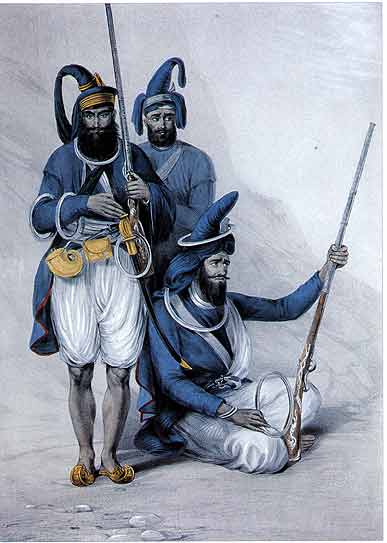

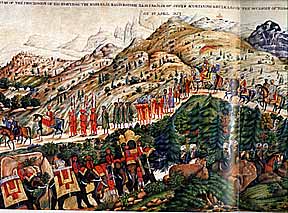

Stimulus for wall painting and frescoes had been provided by religious establishments like Gurudwaras and the various dharamsalas and akharas like those of the Udasi and Vaishnava sects all over Punjab, and the large establishments at Pindori and Damthal. Since Sikhism was a very open religion the Hindu pantheon and legends provided for some images, and common celebrations of Hindu festivals deepened the bond. The themes from Hindu myths and epics included those of the Bhagwat Puran, Ramayna and Mahabharatha. Also painted were incarnations of the various avatars of Vishnu like Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Vamana (fish, tortoise, boar, dwarf), Shiv and Parvati, Lord Ganesh with Riddhi and Siddhi. Popular themes were the churning of the ocean and the lifting of mount Govardhan by Krishna and his hoIi lila, chira harna and daan lila were vividly painted. Also shown are Dharmaraj and heaven and hell themes. There were ragini, baramasa and nayita themes, as well as the love stories of the Mirza Sahiban, Heer Ranjha, Sohini Mahiwal, Sassi Punnu and Laila Majnu. A favourite subject of the muralists were the janamsakhi series of Guru Nanak, or depicting him with the other Sikh Gurus. Guru Gobind Singh, mounted on his horse and with his falcon, was prominently painted. Martyred sons of Guru Gobind Singh and other heroes were also painted. Some of the best murals in Amritsar are in the akhara of Balanand which was founded in 1775 AD. There is also a janamsakhi series in the Baba Atal Gurudwara, in the vicinity of the Golden Temple. This Gurudwara was built in honour of Guru Hargobind Singh in the late eighteenth century and the janamsakhi paintings appeared to have been done in the late nineteenth century. Apart from the religious themes and images of the Sikh Gurus, portraits of rajas and maharajas, courtiers, nobles, generals, jagirdars, sardars and martyrs were profusely painted. Ranjit Singh and his sons were profusely painted on walls in Lahore and Amritsar, and so were the respective rulers in the other Sikh states. The Nihangs made colorful subjects, including the Akali Phula Singh. According to the accounts of travellers even the European generals in Ranjit Singh's court patronized muralists and had done in their residences murals on a wide range of themes, including those from their home countries. Specific occasions were also painted for posterity, one of the famous ones being the meeting of Raja Ranjit Singh with the Governor General Lord William Bentinck, at Ropar in October 1831. After the collapse of the Lahore court the Anglo-Sikh wars were often painted by muralists, who were often the masons who built the structures. Many other akharas, temples and samadlus (tombs) also had wall paintings, all over Punjab, but are now in disrepair, some having been pulled down already.

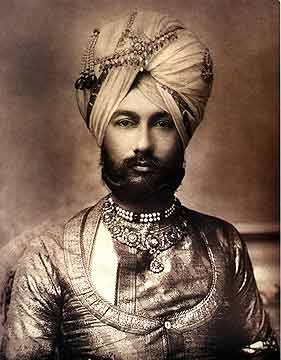

When the first wave of European artists left Punjab in the middle of the

nineteenth century, they were soon replaced by a new group of artists, all

over India, working in the new medium of photography. Photographic processes

were discovered in Europe in 1839 and it took a decade for them to become

commercial. In 1848, this medium came to India and soon commercial photographers

were established in Bombay and Calcutta, though they were not many. The first

Indian photographic society was founded in Bombay on October 3, 1854, followed

by those in Bengal and Madras the next year. Competing with professional establishments

for attention were amateur photographers, who were often employees with the

East India Company and army officers. The various census reports were soon

embellished with the portraits of 'natives'. Lord Canning, the Viceroy at

that time, and Lady Canning were great patrons of photography and encouraged

civilian officers to photograph native lifestyles and submit them. Before

long, by 1865, the India Office in London was deluged with over 100,000 photographs

of Indian subjects. Between 1868 and 1875 the treatise 'The People of India'

was published in London, in eight volumes. Anthropologists delighted themselves

with this new medium to illustrate visual proofs of their research and theories,

like Risley's famous conclusion that, "In India the status of a man is

indirectly proportional to the width of his nose", since proto-australoid

tribals had short and flat noses! The folks back home got to see the 'tough'

lives of their compatriots in the colonies, with the incredible mix of tribes

and castes, trying to improve their lot. The Mutiny also gave rise to the

spirit of photo-journalism in the photographers.

Samuel Bourne was amongst the leading British photographers and, like many artists, had switched over from painting to photography, and continued to indulge in both. He came to India in 1862 and became associated with the firm of Bourne and Shepherd, and photographed people, princes and places. Bourne and Shepherd also brought out a book in 1874 titled the 'Photographs of Architecture and Scenery in Gujarat and Rajputana'. Others like Maurice Portman reached out to the Andaman islands. The Archeological Survey of India was established in 1870 and the British took great pleasure in documenting photographically the immovable assets of the Raj. Amongst the leading Indian photographers was the great Lala Din Dayal, who established shop around 1862 and was the official photographer of the Nizam of Hyderabad. The maharajas continued to be the greatest patrons of this new art and some, like the Maharaja of Benaras, employed permanent court photographers. All of a sudden the art of portraiture had been liberated from the confines of royal courts and made accessible to any one who was interested, could understand the new processes and afford to set them up. For the benefit of women in purdah there were even zenana studios. Punjab and the Sikhs too had their share of photographic documentation. Perhaps the first British photographer to leave photographic impressions of Punjab was John McCosh in 1848. The other photographic firms operating in Punjab, besides Bourne and Shepherd, were Sachs and W. Baker, founded in 1862. Some great photographs of Punjab were taken by Felice Beato in 1857-58, on his going there in search of post-Mutiny images. The convenient realism of the photographic print, which could also be tinted, was the final blow to the art of traditional miniature painting.