|

The Illustrious Women

of Punjab

Punjab is the home of Mata Kaushalia and Mata Sita who begot her twin

sons, Luv and Kush. Luv founded the great historical city, Lavpur,

now called Lahore. Kush founded an equally famous town, Kasur. The

role of Punjabi women as commandos in the battle-fields is no less glorious.Sada

Kaur is remembered as one of the greatest generals of her time even in

the Afghan records.

Mata Sita with Lav & Kush

-------Lav & Kush

being trained by Sage Valmiki

Whenever a male (and if he is not a chauvinist, then in the eyes of Punjabi

women, he is not man enough) begins to write about women, his first natural

impulse, is to unearth the

'Crooked rib'. He looks for a saucy Delilah who tricks Samson and robs

him of his power. A bewa faa (the promiscuous English have no synonym

for this sentimental word which can only be translated into 'faithless'

at best) wife like that of King Bhartrihari who would secretly pass on

as precious a gift as that of the 'fruit of eternal life' amarphal graciously

given by her husband, to her paramour, a mere keeper of her husband's

stables; or a Kaikai who would not stop short of creating storms in the

life of a prophet. But the Punjabi woman falls to oblige this chauvinist

in the search or re-search.

As opposed to Kaikai, Punjab is also the home of Mata Kaushalia, the selfeffacing

wife who would not thwart a commitment made by her husband to a rival,

even when that would make her own life an unmitigated agony. Mata Kaushalia

is the blessed mother of a prophet who is the soul of the scripture Ramayana

that sustains till today. Her birthplace is at Ghuram, which is situated

on the ancient highway that connected the Shivalik to the Aravali range.

Ghuram is a village in Patiala District, which has become a site of revealing

historical excavations.

At Ram Tirath, not far from the city of the Golden Temple, Amritsar is

the landmark com-memorating Rishi Valmiki's hermitage, where Mata Sita

begot her twin sons, Luv and Kush. Luv founded the great historical city,

Lavpur, now called Lahore. Kush founded an equally famous town, Kasur,

about 40 miles east of Lahore. Both these places are in Pakistan today.

In his autobiographical composition entitled the Vachhitar Natak (The

Marvellous Drama), the tenth Master of the Sikhs traces the origin of

the castes of the Bedis and the Sodhis to the dynasties of Luv and Kush.

Guru Nanak, the prophet of Sikhism was a Bedi, Guru Gobind Singh was a

Sodhi.

Punjabis venerate Mata Sahib Devan as the mother of the 'Khalsa'. She

outlived her husband Guru Gobind Singh. She saved Sikhism from the schism

into which it was about to fall after Banda's death. It was at her bidding

that the martyr-saint, Bhai Mani Singh, was appointed the head-priest

of Harimander, now famous as the Golden Temple. Jassa Singh Ahluwalia,

leader of the Sikh Confederacy before Ranjit Singh, was given the title

bandhi chhor or the severer of the fet-ters by the ladies of the Punjab.

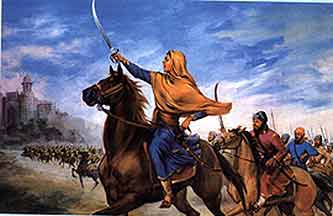

Sada Kaur, the brave mother-in-law

of Maharaja Ranjit Singh

The role of Punjabi women as commandos on the battlefield is no less

glorious. Sada Kaur, the mother-in-law of teenaged Ranjit Singh, shadowed

her son-in-law in all his major engagements against the Mughals especially

after the Afghans had routed the Marathas at Panipat and became so powerful,

that the Moghul throne survived but only under their duress. She is remembered

as one of the greatest generals of her time even in the Afghan records.

Rani Sahib Kaur, sister of the infant ruler Sahib Singh of Patiala, successfully

defended her brother's kingdom against the attacks of the Marathas, Afghans

and European adventurers like George Thompson and chased them away from

the battlefield.

In the Sikh Ardas, God's name is taken thrice at the mention of 40 Muktas.

Mukta is a word derived from mukti or moksh which means' release from

the bondage of maya. These forty souls would have been remembered as black

sheep, but for the intervention and action of a Punjabi lady called Mai

Bhago. Pressed by the Moghuls, Guru Gobind Singh was leading his small

force through guerilla routes towards the desert areas of Punjab around

Khiderana, so that for lack of victuals and water, the large Moghul force

would become inoperative. The hardships caused to the Sikh force in this

inhospitable tract were no less painful. Under the strain of the misery

forty war-riors of the Guru's force led by their commander, Mahan Singh,

wrote a note of desertion to the Guru and fled the field. However as they

reached their houses, their womenfolk, under the influence of Mai Bhago,

refused to let them enter their homes and lamented at them endlessly,

"You wear the bangles and run the kitchen while we join the Guru

on the battle-field." The taunt proved too sharp for the erstwhile

warriors who decided to return to the Guru and to the battlefield. Mai

Bhago took them under her command on their return journey, to ensure

that they would not escape somewhere else.

Mai Bhago

By the time these forty saint soldiers, under their female

commander reached Khiderana , the Guru was already engaged in a battle

with the Moghul forces. Mai Bhago's band surprised the Moghul commander,

who was already being stiffly tried by the Guru's forces. By the time

he decided to run from the field, only wounded Mahan Singh was left alive

gasping for breath. The bodies of others, including that of Mai Bhago

lay dead on the battlefield. Soon the Guru was at Mahan Singh's side;

"Be so gracious as to tear our note of desertion", were the

last words he uttered before his Guru as he breathed his last Because

of Mal Bhago's sacrifice, the dune of Khiderana is the flourishing city

called Muktsar, the giver of redemption.

Punjabi beauties, Heer, Sassi, Sohni; Sahiban, have immortalised a woman's

love for her lover. Anarkali suffered cruel decimation at the hands of

Akbar the great, but did not forsake her love for Shahzada Saleem. Today,

she lies buried in a street in Lahore which bears her name. This bazaar,

Anarkali, is as much the soul of Lahore as Chowringhee is Calcutta's or

Chandni Chowk, old Delhi's.

The poet has been able to epitomise the great beauty of the Punjabi women

only in images. Eyes like a doe's , lotus hands and feet, waist thin as

a spindle and swaying like a whiplash, the gait of a peacock, voice like

a nightingale's, hair like sunlit cascades and complexion glowing like

amber: such are the images through which the Punjabi has cherished the

beauty of his consort throughout the ages. So compulsive is the beauty

of the Punjabi women, that people have noticed it in spite of themselves

and in spite of the context under which they are looking at the Punjab.

To quote a few lines from Mahatma Gandhi's writings:

"God be thanked that the beautiful women of the Punjab have not yet

lost the cunning of their fingers ". vol. XIX p.453). The Mahatma

was admiring the ability of the Punjabi women in spinning but could not

help commenting on their beauty and slender figures.

The women of Punjab had an equal share in the re-building

of India through Kuka, Nirankari, Arya Samaj, Dev Samaj, Congress and

Akali movements and played an equally commendable role in the freedom

struggle against the British.

Noor Jahan, Amrita Shergil and Amrita Pritam hold a place of pride in

music, painting and literature. Social worker and freedom fighter who

was put in jail for her patriotic activities, Raj Kumari Amrit Kaur

gave up the pleasures of a princely home to fight for the independence

of India. This princess of the Kapurthala ruling family, became the first

Health Minister of India. Captain Surinder Kaur, one of the commanders

of the Rani Jhansi Regiment of the Indian National Army, gave her life

while fighting for India's independence in Assam.

Raj Kumari Amrit Kaur

It was a lady from the orthodox Kashmiri Brahman family

of Lahore, Smt. Swarup Devi, whose quiet influence 'was to mould the whole

lifestyle of the Nehru~. She kept the lamp of Indian culture burning in

a home deeply swayed by Western influences, and gave India one of her

most precious jewels Jawaharlal Nehru.

"From the simplicity, freedom and modesty of the women of Punjab,

the Gujarati women have a lot to learn," said Gandhi. (ibid Vol.

XIX p.453).

(Article courtesy Joginder Singh from 'Women of Punjab' by Yash Kohli)

Status of Women

in Sikhism

Guru Nanak rendering Gurbani

Sangeet

With the decline of the Vedic era, and the influx of

foreign marauders all over India, the status of women deteriorated rapidly.

At first, women were secluded for their protection; later, subordination

became the rule of the day. When Guru Nanak

came on the scene, the position of women In India was indeed miserable.

He wanted to build a nation where dignity was accorded equally to men

and women. In'Asa dl Var,' Guru Nanak asks, "Why then revile women,

who giveth birth to great heroes?"

The early civilisation of the Mediterranean and the great river valleys

of the East, differentiated between the roles of man and woman. Aristotle

opined that woman was less complete, less courageous, weaker and more

impulsive than man.

In India, the position of women deteriorated in the post-Vedic era. Ignorance

was widespread, as education was restricted to the upper strata of Hindu

society. Conditions worsened con-siderably alter the invasion of Mohammed

Ghori. Due to lack of security, women were secluded for their own protection

and the purdah system came into vogue. Facilities for education, which

had been restored, to a certain extent by those who conducted Buddhist

monasteries, also vanished. Continuous invasions shattered the political

structure and caused great upheavals in the social conditions of the country.

Women suffered the most. They were by and large, confined to the four

walls of their homes and subjected to the dominance of the male members

of the family. Polygamy was legal and permissible. Child marriage and

infanticide were widespread. Widows were forced to burn themselves on

the funeral pyres of their husbands. History is replete with instances

when women were taken as slaves by the invaders and sold as cattle in

foreign markets.

When Guru Nanak came on the scene, the position of women in India was

indeed miserable. The Guru felt the need to rehabilitate women to a place

of honour. He stressed the need for women to be active and participate

equally in social, cultural, and religious pursuits with men. He asserted

that men and women shared the grace of God equally and were responsible

for their deeds before Him. The Guru repudiated the notion that women

were inherently evil and unclean. He wanted to build a nation where dignity

was accorded equally to men and women. The Guru believed that the social

structure would remain weak and incomplete without the participation of

women in social and religious activities.

Bhai Gurdas sums up beautifully the Sikh attitude towards women: "Woman

is one half of the complete personality of man and is entitled to share

secular and spiritual knowledge equally." Unlike orthodox Hindu belief,

a woman does not have to wait to be reborn as a man to achieve moksh;

she has as much right to attain God in this life. Bhai Gurdas further

regards an ideal woman as the gateway to spiritual liberation for man

himself. Thus, the position bestowed on women in Sikhism by the Gurus

has been unique.

The noblest role assigned to a woman by the Guru was that of a loving

wife and companion. She is exhorted to bring happiness to herself and

to her family by cultivating the qualities of fideli-ty, sweet temper

and loving obedience; these certainly do not amount to subordination,

but form the only possible basis on which true fulfilment can be achieved.

He visualised her as Grihalakshmi-the harbinger of bliss in the home.

This role corresponds with the duty laid upon men to he faithful husbands,

the benevolent and responsible paterfamilias. The state of the householder,

the Grahasth, was given greater im-portance than that of the enforced

celibate, who was held to he the ideal man at that time in India. The

attitude of the sanyasi, who abandons his home, was denounced for its

barrenness and misan-thropy.

The Gurus elevated the concept of conjugal relations between men and women

to a spiritual level. According to Guru Amar Das, the test of a successful

marriage was the complete identifica-tion of the man and the woman with

each other. Those who simply live together are not truly husband and wife,

but those who are united in spirit as well. To ensure marital bliss which

was con-ducive to spiritual progress, the Gurus laid a high moral code

of living for both husband and wife.

Sikh baptism was available to men and women. The Gurus were the greatest

emancipators of women and they condemned those who denigrated them. In

Asa di Var, Guru Nanak asks, "Why then revile woman, who giveth birth

to great heroes?"

The Sikh Gurus were the first to protest against the evil of Sati. Guru

Amar Das said, 'Blessed are those satis, who lead a life of contentment

and chastity."

Equality was conferred on women in the Sikh religion, without them asking

for it. They were, on the other hand, exhorted and made conscious of their

handicaps and rights. Elsewhere, women had to fight to ameliorate their

lot, and still continue to do so.

The ladies in the Gurus' households were the first to demonstrate the

important role that women were destined to play in the development of

the new social order and consciousness that the Gurus were striving to

create. Behe Nanaki, the loving sister of Guru Nanak, and Mata Khivi,

the noble wife of Guru Angad, were pioneers in this respect. They actively

participated in assisting the Gurus in their divine mission.

In the early period of Sikh history, the role of Sikh women was largely

confined to religious and social spheres. But, as circumstances changed,

Sikh women showed their qualities of courage, bravery and sacrifice.

During the governorship of Mir Manu (174&1753), the Sikhs were fiercely

persecuted. Sikh women stood side by side with their husbands and did

not hesitate to hear the brunt Thousands of women, along with their children,

suffered inhuman tortures in the prison cells at Lahore, where the Gurdwara

Shahid Ganj now stands. History does not record a single instance when

any one of them budged an inch from her faith in the Gurus. Sikhs recall

the heroic sacrifices of these brave and noble ladies in their daily Ardas.

Later, during the time of Sikh misals, or independent principalities,

numerous Sikh women distinguished themselves as politicians, diplomats,

administrators and regents. Many Sikh women led forces and fought against

the enemies with great courage. They won laurels not only for themselves

but also for the whole community.

In recent years, during the Gurdwara Reform Movement,

a large number of Sikh women, along with their men, suffered untold atrocities

at the hands of the British. During the partition of the country

in 1947, deeds of valour and self-sacrifice that are too many to he recounted

here. They suffered cruelty and torture but refused to waver from the

path of the Gurus. Their heroic tales ring in our ears and remind us that

our women are in no way behind their men in their sacrifices and courageous

deeds.

Volumes can be written about the glory of women in Sikh history. Today,

many distinguished Sikh women serve the country in various spheres, as

eminent administrators, doctors, educa-tionists, and businesswomen. In

the role of housewives, they are counsellors and the inspiration to create

a happy and spiritual atmosphere in the home for their men and children.

In Sikhism, women have not only been considered equal to men, but they

have played a positive and significant role in Sikh history. They proved

their mettle in whatever sphere they choose to serve. They have stood

shoulder to shoulder with their men in war and in peace, in religious,

social, and political service, and in other walks of life. Every chapter

of Sikh history is full of the adventures and sacrifices of these great

women who have helped to make the Sikh community what it is today.

(article courtesy Harbans Singh from 'Women of Punjab' by Y.Kohli)

Daring Daughters of Punjab

It was during the Freedom Movement that the Indian women proved that

they were made of sterner stuff. They toiled, they fought, they sacrificed.

They believed in what they did. Indian history has recorded the astonishing

vitality and matchless deeds of the daring daughters of India, who continue

to serve the country in fields almost unknown in the past.

The concept of patriotism has always been uppermost in the Indian mind.

The sentiments of love and service for India are to be found in the Vedas

and the epics. In the Manu Smriti, it is said: "Mother and Mother

country are greater than heaven." History has taken note of India's

long and glorious fight in the cause of freedom. Women's participation

in the struggle for independence is well acknowledged. They too were soldiers

of freedom, serving their motherland. Suddenly they were everywhere-nursing

the wounded, picketing courts, legislatures, shops, burning foreign goods,

collecting funds, donating their precious ornaments, even courting arrest

and going to jail.

Mahatma Gandhi expected great things from the Indian women. He once wrote:

"To call women the weaker sex is libel.... If non violence is the

law of our being, the fliture is with the women."

At the age of sixteen, Raksha Saran, daughter of the late Raizada

Hans Raj Sondhi met Mahatma Gandhi. She did not have to leave her comfortable

home or give up her studies. But she did that to follow Gandh Ji into

the villages. Later, she married an eminent political worker of Delhi,

Raghu Nandan Saran. From freedom fighting to social welfare was a natural

step. Her contribution to the field of social work was so impressive,

that she came to be called "a monumental pillar': She chaired the

Delhi Social Welfare Board for fourteen long years.

When rank communalism and destruction were the order of the day innocent

people become helpless witnesses to partition. The years that followed

1947 found the same scenes repeated. At that time, if there was one person

who toiled hard for peace, it was Subhadra Joshi-freedom fighter,

politician, social worker and onetime member of the Lok Sabha. Her Shanti

Sena and anti-communalism committee acted faster than the rioters. Even

to this day, Subhadra has remained a champion of freedom. She has valiantly

fought for the rights of women, boldly questioned the prevailing inheritance

system, and supported slum improvement, the nationalisation of banks and

the abolition of privy purses. Subhadra Joshi also worked to rehabilitate

destitute women, favoured the Rickshaw-pullers' Union and the Coffee House

Workers' Co-operative.

In Raj Kumari Amrit Kaur, we find

yet another vital Punjabi personality. As the princess of Kapurthala,

Raj Kumari Amrit Kaur was educated in England. A staunch disciple of Mahatma

Gandhi, she remained his trusted secretary for many years and was associated

with the All India Women's Conference, of which she became the president

ultimately. Her wise statesmanship and quick wit steered the A.I.W.C.

safely through the difficult period of political unrest. Rai Kumari Amrit

Kaur was jailed in 1942, during the Quit India MovemenL She played a leading

role in the Conference campaign for women's franchise. Her logical evidence

and support of the memorandum for equal rights and status for women in

the new Constitution of India, deeply impressed the committee. She won

similar distinction in England in 1932, by her evidence before the Joint

Parliamentary Committee on behalf of the Women's Association of India,

and she be -came the first Union Health Minister.

The servers of the cause of freedom have been many. Among them Kartar

Devi Puri, a social and political worker, toiled with Shaheed Bhagat

Singh till his death. Shanti Devi Punia, a woman of integrity

has done remarkable social work in Jind. Prem Kaur Chahal belongs

to a well-known family of freedom fighters. Functioning from Sangrur,

her efforts have been directed towards the improvement of moral and social

hygiene. Harcharan Kaur Gill, an M.A., L.T. and member of the Management

Board, Punjab Agricultural University, has fought for freedom and is closely

associated with the Central and State Social Welfare Board and the I.N.A.

Another name associated with freedom movement is that of Jathedarni

Man Mohan Kaur. She is vital and fascinating, and is closely connected

with several women's welfare associations.

Amongst active freedom fighters of a bygone era, several names come to

mind: Ishari Devi Maini, who must now be in her nineties, Rajdani

Dhall, who may be living in Jullundur and was at one time an active

participant in the All India National Congress, Anna R. George Malhotra,

the first Indian woman to be appointed in the I.A.S. in 1950, Sarla

Grewal the first Punjabi woman to hold the position of Deputy Commissioner

and District Magistrate, Simla. She was also the Director, Education in

1960-62. At present Sarla is the Secretary of the Social Welfare Department

in the Government of India.

When Amrita Grover got an appointment in the Indian Audit and Accounts

Service in 1957, a major furore was created. Amrita says: "That was

not my appointment. It was the appointment of the faith and belief that

women can do full justice to the responsibilities handed to them."

Amrita Grover was again the first woman to be appointed Accountant General

in 1975. Today she is a member of the Audit Board and Director of Commercial

Audit. Punjab can well be proud of this distinctive daughter.

Some women are more equal than others. Manorma Bhalla is one such.

Right now, she is busy keeping the Indian Council of Cultural Relations

constanfly in the news. She has won many scholarships, awards and prizes

for her academic performance. At present Manorma is the Ambassador-designate

to Denmark. Dynamic Kapila Vatsayan projects the depth and beauty

of Indian culture. Educated in Michigan, she is a Fellow of the Sangeet

Natak Akademi, a recipient of the Nehru Fellowship and the author of several

books on Indian dance and art, monographs and papers. Kapila is the disciple

of Achhan Maharaj for Kathak, and Guru Amobi Singh for Manipuri dance.

She is also the chief head of Cultural Affairs in the Ministry of Education

and Youth and Youth Services.

There are many more women who have and are still receiving recognition

in their respective fields: Deepak Sandhu, Prem Lal, Veena Sikrl, Nirmala

Prakash and Santosh Chowdhary are some of them. Santosh Chowdhary

is the youngest and the only lady member of the Punjab Public Service

Commission. Arti Khosla, a writer of poetry and fiction, is the

Finance Officer, Indian Railways Accounts Service. Sarla Khosla

has served as Deputy Director, Libraries, Research and Museums, in Jammu

and Kashmir. Ravneet Kaur went on to become Director, Tourism, Cultural

Affairs, Archaeology and Museums, in the Punjab Government. The list is

unending. In our times, there are many fields thrown open to women-fields,

which were almost unknown in the fifties.

(Article courtesy Saroj Vasishth from 'Women of Punjab' by Y.Kohli.)

The

Rich Heritage

of Folk Arts

The main expressions of the Punjab folk arts are theatre, music and

dance. The folk theatre forms are the naqal (dance dramas) and the swang.

The main schools or gharanas of music are Patiala, Talwandi, Sham Chaurasi

and Malerkotla and the dance forms are the vigorous folk dances like the

jhoomer, giddha and the classical kathak.

There are three performing arts in Punjab - theatre, music and dance.

FOLK THEATRE~: The folk theatre forms of Punjab are

the naqal and the Swang. These forms have much in common with other forms

of folk theatre in India, particularly in the North, and are descendants

of the desi form of Sanskrit theatre. The swang is generally personified

by amateurs in Punjab, and by hereditary actors in the State of Haryana.

Naqal is accepted as the main folk form, and is performed by the tribe

of naqals. The word naqal is of Arabic origin, and the content of the

plays is considerably influenced by stories from the Middle East. The

form, however, is classical, at least 150 years old. There is a storyteller

character in all the plays. The former relates the story, making interesting

and caustic comments, particularly on current topics. Most of the dialogue

is traditional, but there is a lot of slick improvisation. The bhand or

jester is a perfect foil who converts all the serious comments of the

storyteller into something stupid yet extremely funny. The humour is lusty

and bawdy, and seldom appeals to an urban audience.

The play starts with a Puravaranga or invocation to the goddess Bhavani.

Puravaranga is not strictly a prologue. The stage is a circular theatre

and the plays are generally performed in the open. There are very few

people and the costumes are changed on the stage itself, one player performing

many parts. The musicians occupy the centre of the stage, often getting

up to sing and dance. Music and dancing is an intrinsic part of any performance.

All parts are played by male actors only. The eunuch or hijra is another

essential character and has been in all margi (classical) and desi (folk

sanskrit) plays. Naqal can be used extensively for communication, because

of the ease with which improvisations on current and popular topics are

woven into the play.

Naqals are hereditary artistes. Though they originally belonged to the

tribe of bhands, they later became a part of the Mirasi tribe. From the

Mirasis, they learnt to sing and dance. The subject matter of their plays

also changed, and they began to perform popular kisse and waran (epic,

romantic and heroic poems). They also began to entertain royalty, and

most Princes had a bhand or naqal at court to entertain them. Merchants

and rich landlords also patronised them. Now that this patronage has disappeared,

naqals have a hard time surviving. Most of them have become agricultural

labourers and only perform occasionally. Ramlila and Raslila can also

be considered forms of folk theatre. The Ramlila is the performance of

the great epic, Ramayana at the time of the Dassera festival in October

or November. It is a massive performance lasting ten days. RamIila is

common to the whole of Northern India.

Raslila deals with the life of Lord Krishna, who is said to have danced

with the nymphs (gopis -below).

MUSIC: The classical form of music here is in Hindustani as opposed

to Carnatic music. It is a much later development, and has only been in

existence for about 100 years. The main schools or gharanas in the Indian

Punjab are Patiala, Talwandi, Sham Chaurasi and Malerkotla. These classical

gharanas are almost dead with the exception of the Patiala gharana the

main exponent of which lives in Delhi. The Malerkotla gharana is still

popular because it is semi-classical and, therefore, appeals to a larger

audience. Nevertheless, Punjabis are very musical and will sit through

all-night performances. At Jullunder, the Haribhallabh festival has been

performed for the last 100 years before a large audience.

Folk music is part of the everyday life of the people. There is no festival

or event in the life of a human being without music and dance. Professional

folk singers include the Dhad sarangia, mirasis, rubabis, gulelna, bhajan

singers and kirtan jathas. Folk music can also be divided into categories

like tappas, bambe geet, dholki-wale geet, and many more varieties.

Religious music is popular. It is not choral singing. The music is based

on classical ragas but it differs only in that the lyrics (which are taken

from the holy books) are as important as the ragas.

Also popular is the singing of love epics and heroic poems. These are

known as kisse and waran. The formers are epic and love poems, while the

latter deal with war and heroism. These are sung, acted and recited, because

in Indian art one cannot separate the arts and music, dance, sculpture,

painting, literature, architecture; these are all co-related and one influences

the other. Heroic epic poems about gods and gurus are very popular.

There are a vast variety of musical instruments: percussion, string recorders,

varieties of flutes, and a host of folk instruments including earthenware

pots and brass trap. Some of the instruments like the tanpura, tabla and

harmonium are used as accompaniments; but the vast majority stands on

their own. The Patiala gharana was once famous because it was played on

the Vichitra Veena. The folk instruments exclusive to Punjab are the algoza

(a double flute) and the dhad sarangi. In short, music can be divided

into four sectors: classical, semi-classical, religious, secular and folk

music.

DANCE: The classical art form native to Punjab is Kathak. Formerly,

the main gharana of kathak was Lahore. Indian Punjab, therefore, has no

practising gharana of kathak dance. Another impediment to the popularity

of kathak is its association with courtesans in this part of India, whereas

in the South arid the East, young girls must learn one of the forms of

classical dancing, in middle and Northern India, respectable women do

not dance.

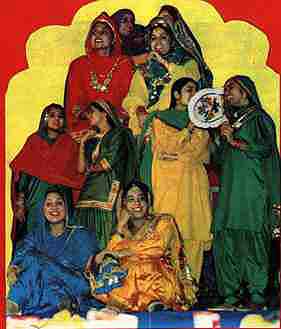

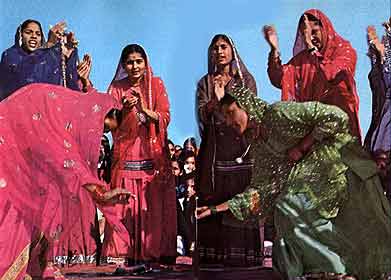

Folk dancing is very popular, and all joyous occasions are celebrated

with music and dance. Women perform a dance called the giddha. It is not

a group dance and is performed by two women at a time. They first recite

a boli and then the whole group sings and claps in rhythm as they dance.

Next follows another pair, and so on. A dholki or (kettle drum) provides

the beat. Dances performed by the men are the bhangra, jhoomer, sialkotia,

pathania and jaisa. With the exception of the jhoomer, the other dances

are very vigorous. The beat is provided by a dholak (or large drum), which

is much louder and booming than a dholki.

The costumes of the male and female dancers are gay and colourful and

are liberally trimmed with gold and silver braids. The giddha,

bhangra and jhoomer are still very popular, but the other dances have

died down. Most of the performers sing, dance and act. They mostly belong

to hereditary families specialising in the art of pure entertainment.

There are also hereditary families of acrobats, mimics etc., like the

Nats, Bhands, Bazigara. etc. The Nats perform tricks and magic besides

dancing. The Bhands are professional storytellers and jesters. Bazigars

are acrobats; and then there are families who display sword fencing, tent-pegging

and mock fights with tall staffs. This is known as gatka and is a very

dangerous and exciting feat. Real weapons are used and tricks like sword

fighting and cutting fruit and vegetables on another's chest are highlighted.

(article courtesy Ravneet Kaur from 'Women of Punjab')

Traditional Folk Dances

Nothing reflects the character of the people more than their songs

and dances. Blessed by the bounty of nature and their own inner strength,

the sons and daughters of Punjab express their joy and gratitude through

their colourful folk-dances and lilting folk songs.

Music, song and dances captivate people everywhere. Their appeal is strong.

Folk dances are an excellent blending of these three arts, and are yet

free from the rigid rules. These

dances begin with the accompaniment of bols (words) and taal (rhythm)

and start in slow

motion like the soft waves of wind, quickening the tempo gradually, ending

like a whirlwind, holding the spectators spellbound throughout.

In most parts of India, folk dances are influenced by religion. Lord Krishna's

Bal-lila (childish pranks) and Premlila (romantic episodes) have been

immortalised through many dance forms. The Rasa-lila in U.P., Keligopal

in Assam, Maharaj in Manipur Dahihandi in Maharashtra and Garba-Rass in

Gujarat, glorify the life of Lord Krishna through dances. Punjab is the

only region where folk dances diverge from religious themes. Except for

the Karthi dance in the Kullu area (now in Pakistan) none of the dances

have religious themes as their basis.

Folk-dances are always performed collectively and without the barriers

of sect or religion. They tend to hypnotise the spectators who involuntarily

clap and sway, if not actually participate in the dancing. The Punjabi

folk dances are a spontaneous expression of the mirth and joy of the toiling

farmers. Therefore no equipment, decor, costumes, stage, light effects,

etc. are required. Any time of the day or night, be it under the sun,

moon or stars, people assemble under the spreading banyan tree in the

village, and in gay spirits perform the bhangra, gidha or jhoomar, with

beats, claps and a few words of a simple song. The sturdy dancers care

little about make-up or costumes. They are blessed with radiant health

and vigour. The jawan gabaroo (strong, hand-some young man) is well built,

broad-chest and tall. The women are bewitching, fair and beautiful. Their

clear complexion needs no artificial colouring. These folk dances do not

relate any story or theme. Therefore the hero's or heroine's role is not

essential.

In many regions of Punjab, the group dances do not have the men and women

participating together. The women have been confined to the four walls

of their homes and they observe the purdah system by covering their faces

with jhund, the dupatta or veil. They are allowed to witness the men-folk

dancing the bhangra, chhaj, jhoomar etc, but their men are forbidden to

watch women dance the giddha, luddi, kutan, jago, sammi etc. Nevertheless,

the ballo and giddha dances can be witnessed by the sons and sons-in-law

of the village on the Teej festival.

The folk dances have boliyan as their composition. It is these boliyan

that enlivens the mood of the dancers.

Essential part of the giddha

is Boliyan

They are traditional but time has made changes in them

too. The boliyan are not composed by a professional person only. Even

a farmer contributes to them. They have a uniform rhythm, and often their

appeal is enhanced by a meaningless rhyme added to them. Almost all folk

dances are performed in circles.

Whilst dancing the giddha, the women sing in sonorous voices, to

the accompaniment of the dholak (drum), ghadda (pots) or to the beat of

clapping. The leader (woman) of the chorus sings the boli, which the chorus

repeats. The ghadda is played by gently striking a ring or a small stone

on it in keeping with the rhythm. It helps to build an atmosphere of gaiety.

The popular folk-dance giddha is performed only by women,

especially on joyous occasions like marriage, mundan (shav-ing of the

hair of a child), the Teej festival or at the time of reaping the harvest

Through the bolis, the women publicly express their innermost feelings.

On such occasions, one has glimpses of their anger, jealousy, love

etc. There is one kind of giddha, in which women cover their faces with

dupattas, chant bhun-bhun and dance to clap-beats. But now, this is not

much in vogue. In the Sangrur district of Punjab, boys also dance the

giddha, but at night to welcome a new bride to the village. Here musical

instruments like dhol (drum), ektara, chimta are used.

Sammi is yet another folk dance of the Punjab performed by women only.

The legend says that this dance was originally performed by Princess Sammi

of Marwad to emote her separation from her lover, Rajkumar Suchkumar of

Rajasthan. It is also said that the lovers belonged to West Punjab. In

this dance, the women make a circle and hold hands to form a chain. They

dance in a circle, making various patterns with their feet. As the dancers

pick up the movements, they break the chain and free their hands, then

they lift up their hands and start snapping their fingers and clapping,

keeping to the rhythm. It is this clapping and snapping which constitutes

a sammi dance. Another form of this dance is called roomal sammi a dance

performed with handkerchiefs.

Ballo is a form of giddha. It is performed mainly in the Malva District,

including Ludhiana and Moga in Punjab. The festival of teej is in full

swing during the month of sawan (July-August). From the third day of the

moon to the full moon day, Teej is celebrated throughout the state. In

this season, married women return to the parental home, where brothers

await them with sindara (sweet pakoras) and malthariya. To celebrate the

reunion with their childhood friends, they dance the giddha every night

under the open sky. On the concluding day of Toeyan (teej), ballo is performed,

after which the young brides return to the homes of their inlaws. In ballo,

the girls form two rows facing each other. In one row, the girls tie their

dupattas on their heads, to represent men wearing the pagris. This dance

also starts with bolis.

Kikli

Kikli is another folk dance very popular with young girls. It is linked

to a folk-song called Kikli. In this dance, two girls stand facing each

other. They cross their arms, holding right hand with left and left hand

with right. They are now prepared to try their vigour, moving round and

round in a fast tempo. This is known as kikli, and is accompanied by folk

songs.

Jago is danced at weddings and is very popular with the women who, during

marriages remain in the house when almost all male members of the village

go away with the baraat This dance keeps them awake, and they perform

it with great zest in spite of the fear of dacoity. The words of the songs

that accompany this dance are fiery.

Bhangra is the liveliest and the most popular folk dance of the Punjab.

It projects the strength of both the body and the spirit of a sturdy race.

This dance belongs to West Punjab (now in Pakistan). On Baisakhi day,

the old and the young join to dance the bhangra, which has become famous

throughout the country. In the month of April, on a full moon night, the

jawan gabaroo looks at his golden field brimming with a rich harvest.

His heart is overjoyed and he cannot resist dancing the bhangra to the

joyous beat of the dhol (drum). Women and children gather to enjoy the

colourful spectacle on the open ground, where the dancers surround the

dholee (the drummer) and with gay shouts of balle-balle or oy, oy dance

with sticks to which colourful ker-chiefs are tied.

The jhoomar dance is performed by the Jangli Seef of Western Punjab.

It is more popular in the region between the Ravi and Chenab rivers. This

dance projects the movements of animals, which the dancers are familiar

with. In olden days, the Janglis danced alongside their animals. The jhoomar

dance is accompanied by the dholak and its rhythm varies from slow to

fast. Men , women and children of the village gather round the dholi as

the air is filled with the joyous rhythm and the sound of dancing feet.

Some of the lesser-known folk dances of the Punjab are ludi, tipri, khara

and kadva. All folk-dances performed solo or in groups, represent the

life pattern, tradition and the folk-art of Punjab. Even in our modern

era, these folk-dances thrive and draw Indians as well as foreigners,

with their graceful lilting movements, music and magic.

(Article courtesy Pramila Mehra from 'Women of Punjab' by Y Kohli)

The Lost Heritage

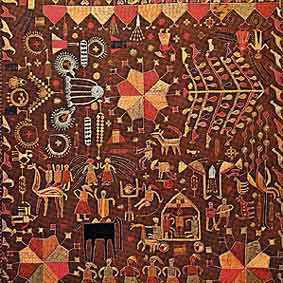

A reference to phulkari in literature comes from Guru Nanak Devji

who wrote: "Kadd kasidha paihren choli, tan tu jane nari" (only

when you can embroider your own choli with the embroidery stitch, will

you be accepted as a woman).

The word phulkari (below) conjures up happy memories of the old

Punjab, which stretched from Peshawar to Delhi and Ladakh to Multan.

It brings to mind several visions of the life of a Punjabi woman of

yesteryears: embroidering her phulkari for her wedding and spinning cotton

on a painted charkha; the elaborate ceremonies of her marriage with the

wedding phulkari draped over her; going out to the fields with a pot of

butter-milk and corn-flakes on her head, dressed in a full yellow skirt

with a black kurta and richly embroidered phulkari covering her from head

to knee; the birth of her sons and daughters and the beginning of embroidering

phulkari for the distant but happy occasions of their marriages; and on

her death, when she is lifted on a bier by her sons, covered with a red

phulkari, the symbol of a happy end, of prosperity, of fulfilment

The word phulkari literally means "flowered work". Its exact

origin is not known. Sir Denzil Ibbetson in his Punjabi Ethnography, published

in 1883, remarks that the tract where the best phulkari work was found

was originally inhabited by Hindu Jats, who were afterwards conquered

by Mohammedan tribes. Another conjecture is that the art was brought by

Gujar nomads from Central Asia. It may also have some association with

the gulkari of Iran which was practised there till very recently.

Though it may have had its origin elsewhere, this form of embroidery

has become expressive of the spirit of Punjab. The warmth and richness

of colours, the bold patterning and the patient hard work which go into

the phulkari make it symbolic of the women of this region.

Perhaps, in some remote period of our history, this form of embroidery

was practised not only in Punjab but in other parts of India as well.

A reference in literature comes from Guru Nanak Devji who wrote: "Kadd

kasidha paihren choli, Tan tujane nari" (only when you can embroider

your own choli with the embroidery stitch, will you be accepted as a woman).

A finished piece of phulkari and particularly the bagh had the dazzling

effect of kin-khab from a distance. The ghungat bagh used to be the most

outstanding form of phulkari popular in the Rawalpindi area. It meant

the "veil shawl" because it had a triangular patch of embroidery

on that part of the shawl, which covered the head---the base of the triangle

covered the selvage and the apex fell on the nape of the wearer's neck.

The suber was a red phulkari with five flowers in the centre. A small

border was also embroidered at the spot where the ghungat covered the

head and face. This was also used in some cases in place of the chope.

The shishadar phulkari had small, circular, slightly convex mirrors sewn

into the pattern, usually forming centre-pieces of flowers in the embroidery

which produced a quaint and fantastic effect. This type of phulkari was

popular in the eastern districts.

According to Samarendranath Gupta, Principal, Mayo School of Art, Lahore,

there was considerable difference between the Hindu and Mohammedan phulkari

art. The difference, which was quite apparent, seemed to be sectarian.

The Hindus, as a rule, had an Indian red and white ground cloth, the Mohammedans

cared more for black cloth. The shades of the floss silk threads also

differed. The Hindus mostly used white, bright orange, gold, deep brown-madder,

deep purple, vermilion and crimson shades. Green was very rarely used,

whereas the Mohammedan generally used green, gulnar, lemon, yellow and

sometimes white. The Hindu work was usually characterised by pattern made

up of regular curves and flowered designs. The Mohammedan work was generally

ftill of regular geometrical figures, which had a Saracenic origin.

Mrs F. A. Steel was a great admirer of phulkari and was the first to write

on this art in 1888.

Accoding to her, the best phulkaris were produced in Hazara district.

In a Punjab exhibition of 1882, Hazara phulkari was awarded the first

place. It was also adjudged the best in the Indian Art Exhibition held

at Delhi in 1903.

Different types of Phulkaris

Phulkari was not exclusively meant for women; it served other purposes

as well. Hindu and sikh scriptures, for instance, were kept wrapped in

phulkaris. When a rare Janam-Sakhi manuscript on the life of Guru Nanak

Devji was lent by the India Office Library, London, to the Government

of Punjab for the inspection of the Lahore Sikhs, coverlets of phulkari

were offered by the Sikh community with a petition that they might be

employed to cover the sacred biography of the Great Guru.

When displayed in exhibitions held in Europe-the Great Exhibition of London

in 1851, of Paris in 1855 and the Amsterdam International Exhibition of

1882-the beautiful phulkaris caught the fancy of Europeans, and demand

for them grew in foreign markets. "Industrial and Mission Schools,"

observed J. L. Kipling, "began to produce Europeanised versions

of phulkaris of quite astonishing hideousness."

A dealer once showed the pattern that had been furnished to him by a European

trader and smilingly observed that it paid him to make such stuff, but

he could not see what the people of the U.S.A. thought beautiful or found

useful in those monstrosities in black, green and red. This is Self-explanatory.

The craft was lost, never to be revived. Maybe the time has come to set

up an exclusive museum of phulkari, the lost craft.

(Article courtesy K.S.Kang from 'Women of Punjab' by Yash Kohli)

The Poets of Punjab

The Punjabi language is a recent one comparatively. There does not

seem to be any tradition of the written word in the language till the

dawn of the present century. Yet in due course, many significant poets

appeared in this, the land of five rivers.

As compared with other languages, Punjabi poetry-as indeed the language

itself-is of comparatively recent origin. Bhai Vir Singh, the beacon light

of Punjabi literature, emerged on the scene as a poet and writer of consequence,

only in the first decade of the present century. So, the time span between

Bhal Vir Singh and Amitoj, Dilip Kaur Tiwana or Manjeet Kaur Tiwana

-still younger contemporaries, is not even a century. From the accounts

available, there does not seem to be any tradition of the written word

in the language before the advent of the present century. It could, therefore,

be safely construed that Bhai Vir Singh is the first writer in the Punjabi

language and literature, as it is understood today.

In due course, a galaxy of significant poets appeared on the skyline of

the land of the five rivers. Notable amongst them being Puran Siugh, Diwan

Singh, 'Kalapani' Mohan Singh, Bawa Balwant, Santokh Singh Dhir, Devendra

Satyarathi, Pritam Singh,'Safeer',Takhat Singh, Amrita Pritam,

Tara Singh, Harbhajan Singh, Prabhjot Kaur, Shiv Kumar Batalvi,

Amitoj, S. S. Mishra, Ravinder Ravi, Sati Kumar, Jagtar and others. From

the land of soil and toil, only a few outstanding women poets emerge and

only Amrita Pritam has made her mark on the international scene, because

of her lyrical sensibility and projected sensitivity.

Manjeet Tiwana......Amrita

Pritam............Prabhjot

Kaur

With the possible exception of Shiv Kumar Batalvi, the best

thing that happened to Punjabi poetry is Amrita Pritam, and the faith

in her is confirmed by the Bhartiya Jnanpith Award bestowed on her. She

is easily the most lyrical of all Punjabi poets. In her poetry is the

oceanic vastness, the hungry haste of rivers, and the slowness of grounded

water. Love in its various manifestations. Love, undefined in the human

behaviour and environment, is her forte. She seems to believe that the

process of poetic creation depends more on the substance and less on images

and metaphors, though these too are abundantly present in her poetry.

Despair and frustration are the other emotions found in her poetry. The

transition from the sentimental and traditional, to realism and bold experimentation

marked a strong new process in her poetry. There is an alarming feeling,

intensity and passion underneath whatever she puts in verse. In a supreme,

highly evocative, autobiographical poem Safarnama Pyas da (Travelogue

of Thirst) she achieves a certain harmony.

Unlike most others whose brilliance withers away with time, Amrita Pritam

seems not to have aged. Though the passing of years has brought about

a transformation in outlook, it is positively reflected in her verse -

a better command over the medium. The subtlety, the poetic afterbirth,

the tone of helplessness and the intensity of experiences are her strong

points. Her verse is emotional in sound but immensely rhythmic and mature,

and the intensity of content covers a wide range of expression not commonly

found in Punjabi poetry. Her recent verse reflects a surprising growth

and change, a breakthrough, so to say. They bear her unique mark-the taut

precision, the sparse subtlety of the Punjabi colloquial idiom and, above

all, the intensity of personal vision, the depth, the diction.

Prabhjot Kaur, who at one time showed considerable promise, is, unfortunately,

lost to rhetoric, in an attempt to consciously emulate, at times even

imitate Amrita Pritam.

To sum up, so long as there are poets' like Amrita Pritam active in the

creative process, there is hope and hope for Punjabi poetry.

(Article courtesy Suresh Kohli from 'Women of Punjab' by Yash Kohli)

LOVERS of PUNJAB

For centuries the saga of the folk lovers, which immortalises the

memory of Heer, Sohni, Sahiban, Sassi and others, has been handed down

from generation to generation. These women who loved did not treasure

their body or soul, they sacrificed everything for love.

Indrani, Sandramata, Roma, Shorvashi, Lopamudra, Natyam Yami, Nari, Saraswati,

Sarir, Lakshmi, Sarparajni, Vaksardha, Ghosha, Medha, Dakishna, Ratri,

Surya, Savitri, Sikta, Nivavari, Brahmvadym Tripta etc. -27 women of ethereal

beauty who were such lovers of knowledge and power, that their creation

became a part of the Rig Veda, on e of the four vedas that was written

on the threshold of the land of five rivers. The others are the Atharv

Veda, Sam Veda, and Yajur Veda.

This was the historical perspective of Punjab which became the heritage

of the legendary

lovers. This is why perhaps, the vision that emanated from the heart of

a woman in the form of folksongs, or the images of women that the poets

collated in their verses are those of Heers and Sassis drawing water from

the wells and streams; working at the spinning wheel; swinging on the

peepal trees; rubbing the unripe soft bark of a walnut tree on their lips;

applying it to their eyes; eating vermicelli pudding and drinking fresh

milk But the poetry and the folk songs of Punab do not depict the woman

as either a legendary figure or a divine beauty, neither a moll nor a

common whore. Her modesty is a part of her conduct. There is a saying

about these fair ladies:

Channa tan ohna de patta vekke sakda

Par Suraj noon vekhan lai tap karna painda.

"The Moon can have a glimpse of their thighs

But the sun has to perform penance to steal a look."

Punjab has always combated invaders. Therefore the truth of life became

a reality like blood in one's veins. All this inculcated in the lovers

of Punjab not only an appreciation and periscopic sense of beauty, but

also the courage to gift life. The action became two-dimensional while

on the one hand mortal love gained the stature of worship of God; on the

other hand, it lent courage to defy religious constraints.

Sufism drew sustenance from the banks of the five rivers-converted the

religious places into abodes of atheists, and rendered holy mosques into

dwelling places for the sinners. They made their hearts and the courtyards

of their homes the abodes of the gods This is the reason why there is

the fragrance of the earth in the poetry of Punjab as well as a smell

of liquor. If in their courtyards the incense is seen burning, the smoke

of separation is also seen rising from the same place.

As long as there is a relationship between life and reality the poetry

of Punjab will never forget the reality of life, even while paying homage

to beauty. For instance the beauty of a woman emerging from a pond after

a bath has been compared to the tantalising flame emerging from an intoxicating

tobacco pipe. She has not been sketched as a heavenly beauty stepping

out from the Mansarovar Lake. She is pictured as an earthy rural beauty.

The beautiful truth is that for centuries the saga of the folk lovers

which immortalises the memory of Heer, Sohni, Sahiban, Sassi and others

has been handed down from generation to generation. Their memories are

still alive, as they had died for love and not because their lovers had

died for them at the altar of love. They rebelled against the conventional

norms of society. These women who loved did not treasure their body or

soul; they sacrificed everything for love.

It seems that the roots of this philosophy are embedded in the poetry

of Waris shah, who believed that the world existed on love. He says:

Avval hamad khuda da virad keeje

Ishq keeta a juga da mool miyan

Pah;e aap Allah ne ishq keeta

Te mashooq hai rabbi rasool miyan

"Be thankful to God

For making Love the root of the world

First He himself loved

Then He. made the prophets

His beloved ones."

It is this belief which endowed the woman of Punjab with a romantic soul

and filled it with the conviction of truth and gave her the courage to

speak. Therefore we do not come across any love story which portrays a

woman pining to death or quietly nursing her love within her bosom. In

all the love tales the women are volatile and have dynamic characters.

It is therefore not at all surprising that one of the folksongs describes

the women proceeding to a religious place Jaito, in the following manner:-

"Today the Sohnis and Sassis are going to the Jaito Fair."

The poet on seeing the women pilgrims thinks of the courageous Sohnis

and Sassis who have been immortalised for their worldly love. The onlookers

bestow the women pilgrims with the same respect and reverence that they

give the lovers, Sohni and Sassi.

Heer Heer

Heer was the daughter of a feudal landlord Chuchak sial from Jhang. Before

her sacrifice for Ranjha, she proved herself to be a very courageous and

daring young girl. It is said that Sardar(chief) Noora from the Sambal

Community, had a really beautiful boat made and appointed a boatman called

Iuddan. Noora was very ruthless with his employees. Due to the ill treatment

one day Luddan ran away with the boat and begged Heer for refuge. Heer

gave him moral support as well as shelter.

Sardar Noora was enraged by this incident He summoned his friends and

set off to catch

Luddan. Heer collected an army of her friends and confronted Sardar Noora

and defeated him.

When Heer's brothers learnt of this incident they told her. "If a

mishap had befallen you why

didn't you send for us?" To which Heer replied, "What was the

need to send for all of you-Emperor Akbar had not attacked us."

It is the same Heer who, when she is In love with Ranjha, sacrifices

her life for him and says,

Ranjha Ranjha kar di ni main aape Ranjha hoi aakho ni mainoon dheedho

Ranjha Heer na aakho koi

"Saying Ranjha, Ranjha all the time I have also become Ranjha. No

one should call me Heer, call me dheedho Ranjha."

When Heer's parents arranged her marriage much against her wishes with

a member of the house of Kaidon, it is Heer who plucks up courage during

the wedding ceremony and reprimands the Kazi (priest) -"Kazi I was

married in the presence of Nabi (Prophet) on the first day. When did God

give you the authority to perform my marriage ceremony again and annul

my first marriage? The tragedy is, people like you are easily bribed to

sell their faith and religion. But I will keep my promise till I go to

the grave."

Heer is forcibly married to Kaidon but she cannot forget Ranjha. She

sends a message to him. He comes in the garb of a jogi

(ascetic) and takes her away. When Heer's parents hear about -the

elopement they repent and send for both of them promising to get Heer

married to Ranjha. But Heer's Uncle Khaidon betrays them and poisons Heer.

Ranjha as a yogi at the door

of Heer

In this love tale, Heer and Ranjha do not have the good

fortune of making a home. But in the folksongs sung by the ladies, Heer

and Ranjha have always enjoyed a happy domestic married life. Whenever

anyone has to forsake society and face such combats, they picturised in

the folksongs;

Chal sakhiye ral vekhan chaliye Ranjhan da chubara,

Heer bechari Intta dhoye Ranjha dhoye gara.

"Dear friend, let us go and see Ranjha's terrace Poor Heer is carting

the bricks and Ranjha is carrying the sand and mud..."

It was Heer's strong conviction, which has placed this tragic

romantic tale on a prestigious pedestal along with Punjab's religious

poetry.

Even the great spiritual poet Bhai Gurdas has compared Heer and Ranjha's

love to the devotion and love of a prophet and disciple for God.

The great poet Waris Shah who made Heer most popular and immemorable,

referred to Ranjha as the body and Heer as his soul.

Heer was a Muslim, but whenever the Punjabi Hindu girls share something

in common with Heer and talk about their life with reference to Heer's

they say -"Pandit Ji please organise and perform Heer's marriage

ceremony today.,, Forgetting at that moment that it is not a pandit nor

a Brahmin who is required for Heer's marriage, but a Kazi (Muslim priest).

This is the strength and force generated by the romantic lovers who place

love at such a zenith that all the religions of the world bow down before

it

Sassi

Sassi was another romantic soul, the daughter of king Adamkhan of Bhambhor.

At her birth the astrologers predicted that she was a curse for the royal

family's prestige so the king ordered that the child be put in a wooden

chest and thrown into a river. The chest was found floating by Atta the

washerman, who was washing clothes on the bank of the river. The dhobi

believed the child was a blessing from God and took her home and adopted

her as his child. Many, many years passed by and the king did not have

another child, so he decided to get married again. When he heard that

the daughter of Atta, the washerman, was as beautiful as the angels, the

king summoned her to the palace. Sassi was still wearing the tabiz (amulet),

which the queen mother had put around her neck when she was taken away

to be drowned. The king recognised his daughter immediately on seeing

the tabiz. The pent-up sufferings of the parents flowed into tears. They

wanted their lost child to return to the palace and bring joy and brightness

into their lives, but Sassi reftised and preferred to live in the hQuse

where she had grown up. She refried to leave the man who had adopted her.

Sassi did not go to the palace but the king presented her with abundant

gifts, land and gardens where she could grow and blossom like a flower.

As all the rare things of the world were within her reach she wanted to

acquire knowledge and sent for learned teachers and scholars. She made

sincere efforts to increase her knowledge. During this time she heard

about the trader from Gaini, who had a garden made with a monument, the

inner portion of which was enriched with exquisite paintings. When Sassi

visited the place to offer her tributes and admire the rich art, she instantly

fell in love with a painting, which was a masterpiece of heavenly creation.

She soon discovered this was the portrait of Prince Punnu, son of King

Ali Hoot, the ruler of Kicham.

Sassi became desperate to meet Punnu, so she issued an order that every

businessman coming from Kicham town should be presented before her. Within

her heart she literally started offering her salutation to Kicham town.

There was a flutter within the business community as this news spread

and someone informed Punnu about Sassi's love for him. He assumed the

garb of a businessman and carrying a bagful of different perfumes came

to meet Sassi. The moment Sassi saw him, she could not help saying, "Praise

be to God!"

Punnu's Baluchi brothers developed an enmity for Sassi. They followed

him and on reaching the town, when they saw the marriage celebrations

of Sassi and Punnu in full swing, they could not bear the rejoicing. That

night the brothers pretended to enjoy and participate in the marriage

celebrations and forced Punnu to drink different types of liquor. When

he was dead drunk the brothers carried him off on a camel's back and returned

to their hometown Kicham.

The next morning when Sassi realised she was cheated she became mad with

the grief of separation from her lover. Crying her lover's name, she ran

barefoot towards the city of Kicham. To reach this city she had to cross

miles of desert land, the journey through which was full of dangerous

hazards, leading to the end of the world.

Her end was similar to the end of the Kaknoos bird. It is said that when

this bird sings, fire leaps out from its wings and it is reduced to ashes

in its own flames. Similarly Punnu's name was the death song for Sassi

who repeated it like a song and flames of fire leapt up and she was also

reduced to ashes.

Sohni

Sohni was the daughter of a potter named Tula; who lived in the Gujarat

district (of Punjab) near the banks of the Chenab river. As soon as the

Suraies (water pitchers) and mugs came off the wheel, she would draw floral

designs on them and transform them into masterpieces of art.

Izzat Baig.the rich trader from Balakh Bukhara,came to Hindustan on business

but when he saw the beautiful Sohni he was completely enchanted. Instead

of keeping mohars (gold coins) in his pockets, he roamed around with his

pockets full of love. Just to get a glimpse of Sohni, he would end up

buying the water pitchers and mugs every day.

Sohni lost her heart to Izzat Baig. Instead of making floral designs on

earthenware she started building castles of love in her dreams. Izzat

Baig sent off his companions to Balakh Bukhara. He took up a job as a

servant in the house of Tula the potter. He would even take their buffaloes

for grazing. Soon he was known as Mahiwal (potter).

When the people started spreading rumours about the love of Sohni and

Mahiwal, without her consent her parents quietly arranged her marriage

with another potter. Suddenly, one day her barat (marriage patty) arrived

at the threshold of her house. Sohni was helpless and in a poignant state.

Her parents bundled her off in the doli (palanquin), but they could not

pack off her love in any doli (box).

Izzat Baig renounced the world and started living like a fakir (hermit)

in a small hut across the river. The earth of Sohni's land was a dargah

(shrine) for him. He had forgotten his own land, his own people and his

world. Taking refuge in the darkness of the night when the world was fast

asleep, Sohni would come by the river side and Izzat Baig would swim across

the river to meet her. He would regularly roast a fish and bring it for

Sohni. It is said that once due to the high tide he could not catch a

fish, so he cut a piece of flesh from his thigh and roasted it. Seeing

the bandage on his thigh, Sohni opened it, saw the wound and wept.

From the next day Sohni started swimming across the river with the help

of an earthen pitcher as Izzat Baig was so badly wounded, he could not

swim across the river.

Soon the breezes had spread the rumours of their romantic rendezvous.

One day, Sohni's sister-in-law followed her

and saw the hiding place where Sohni used to keep her earthen pitcher

amongst the bushes. The next day her sister-in-law removed the hard baked

pitcher and replaced it with an unbaked one. At night when Sohni tried

to cross the river with the help of the pitcher, it dissolved in the water

and Sohni was drowned. From the other side of the river, Mahiwal

saw Sohni drowning and jumped into the river.

This was Sohni's courage, which every woman of

Punjab has recognised, applauded in songs and written about: "Sohni

was drowned, but her soul still swims in the river...

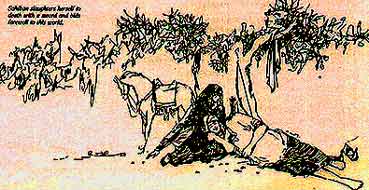

Sahiban

Sahiban was another love-lorn soul. Shayer Piloo raves about her beauty

and says,"As Sahiban stepped out with a lungi tied around her waist,

the nine angels died on seeing her beauty and God started counting his

last breath…"

When this beauty is about to be wedded forcibly to someone else by her

parents, without any hesitation she sends a taunting message to Mirza

whom she loves, to his village Danabad, through a Brahmin called Kammu.

Chal Sahiban de viah di mehndi

Toon apni hathin la de"

You must come and decorate Sahiban's hand with the marriage henna."

"This is the time you have to protect your self-respect and love,

keep your promises, and sacrifice your life for truth." Mirza was

also a young full-blooded man who had self-esteem. He makes Sahiban sit

on his horse and rides away with her. But on the way, as he lies down

under the shade of a tree to rest for a few moments, the people who were

following them on horseback with swords in their hands catch up with them.

Sahiban was a virtuous and a beautiful soul who did not desire any bloodshed

to mar the one she loved. She did not want her hands drenched with blood

instead of henna. She thinks Mirza cannot miss his target, and if he strikes,

her brothers would surely die. Before waking up Mirza, Sahiban puts away

his quiver on a zand tree. She presumes on seeing her, her brothers would

feel sorry and forgive Mirza and take him in their arms. But the brothers

attack Mirza and kill him. Sahiban takes a sword and slaughters herself

and thus bids farewell to this world.

Innumerable folk songs of Punjab narrate the love tale of Sassi and Punnu.

The women sing these songs with great emotion and feeling, as though they

are paying homage to Sassi with lighted diyas at her tomb. It is not the

tragedy of the lovers. It is the conviction of the heart of the lovers.

It is firmly believed that the soil of the Punjab has been blessed-God

has blessed these lovers. Though their love may have ended in death, death

was a blessi~ig in disguise, for this blessing is immortalised.

Waris Shah who sings the tale of Heer elevates mortal love to the same

pedestal as spiritual love for God saying, "When you start the subject

of love, first offer your invocation to God" and this has always

been the custom in Punjab, where mortal love has been immortalised and

enshrined as spiritual love.

Just as every society has dual moral values, so does the Punjabi community.

Everything is viewed from two angles, one is a close up of morality and

the other is a distant perspective. The social, moral convictions on one

hand give poison to Heer and on the other make offerings with spiritual

convictions at her tomb, where vows are made and blessings sought for

redemption from all sufferings and unftilfilled desires.

But the Sassis, Heers, Sohnis and others born on this soil have revolted

against these dual moral standards. The folk songs of Punjab till today

glorify this rebelliousness.

Chadar phatey tan see lavan

Ambar phatey tan kiddan seewan

Khamid mare hor labhlavan

Ashiq mare tan kidda jeewan

"When the sheet tears, it can be mended with a patch; how can you

darn the torn sky? If the husband dies, another can be found, but how

can one live if the lover dies?"

And perhaps it is this courage of the rebellious Punjabi woman, which

has also given her a stupendous sense of perspective. Whenever she asks

her lover for a gift she says -Mainnoo ambar da lahenga siwa de ve

Ohnoon dharti di kinari lawa de ve

"Get a skirt made for me of the sky, And have it trimmed with the

earth."

(Article courtesy Amrita Pritam from 'Women of Punjab' by Yash Kohli)

Stars of the Silver Screen

Punjabis play a dominant role in most spheres of the Indian film industry

as producers, directors, editors, writers, musicians and artistes. Though

Punjabis have contributed a great deal to the success and growth of Hindi

films they have tended to neglect Punjabi films. Financial viability has

been the reason why stalwarts like Raj Kapoor, B.R. Chopra and others

have not directed their talents towards Punjabi films. Hopefully the Punjabi

film industry will make rapid progress and establish itself like other

regional films, which have won international acclaim.

Most Punjabi film actresses quit the industry after marriage. Nargis,

Geeta Bali and Bina Rai left films at the very peak of their careers.

There are many Punjabi male stars who do not allow their wives, sisters

or daughters to make films a career yet the sons are encouraged to make

spectacular debuts-a film career has become hereditary only for the Punjabi

male, apparently.

Sohni-Mahiwal, Dulla-Bhatti, Sassi-Punnu, Heer-Raniha, Mirza-Sahiban-immortal

legendary lovers whose tragic lives are spun into lyrics even now. The

Punjab has echoed with these

exotic tales for many years. Eminent poets, from Bulle Shah to Amrita

Pritam, have rendered these legends in poetry.

With the advent of cinema, these divine love poems have been preserved

for posterity on the screen. Those who played the roles of the lovers

have also gained immortality with their moving portrayals. Innumerable

variations of the theme-immortality of the lover and beloved achieved

after death continues to influence Indian cinema.

Punjabi women have pioneered romantic musical extravaganzas. Since the

thirties, these actresses have captured the hearts of audiences everywhere

with their stunning looks and proven talent.

The first and only, Indian "talkie" that had thirty songs was

Laila Majnu (1932). The girl who played Laila was Kajian, a young beauty

born and bred in the Punjab. Noor Jehan, the great singer from the Punjab,

came, saw and conquered the Indian film world with a single appearance

on the screen. Playing the role of Dilip Kumar's beloved in Jugnu, she

set a trend in the filming of musicals, and became a singing star overnight.

After thirty years, her songs still ring in our ears. Noor Jehan was born

and grew up in Lahore. She fell in love with, and married director Shoukat

Hussein before the completion of Jugnu and migrated to Pakistan after

the movie's silver jubilee in 1948.

Bombay Talkies' Kismet ran for three years in a single theatre at Calcutta.

Mumtaz Shanti, famed for her hypnotic eyes, starred in the leading role.

An alert producer spotted her on the streets of Lahore, and launched her

to fame. Tansen, produced by Sardar Chandulal Shah, bagged all the awards

available at the time it was made. Considered one of the classic films

made in India, the memorable role of Tani was enacted by Khurshid, another

singing star from Lahore. Her pairing with the immortal K. L. Saigal created

a sensation throughout the world of music.

Sardar Akhtar elevated the status of women in Aurat, made by her famous

husband the late

Mehboob. Her ethereal beauty captured the heart of Mehboob, who eventually

married her.

Mehboob later admitted that it was Sardar Akhtar who inspired him to make

such landmarks as Aan, Andaz, and that all time great movie, Mother India.

Sardar Akhtar's performance as a

dhoban (washerwoman) in Pukar, also displayed her skilled histrionics.

Nasreen, the Roohi of director A. R. Kardar's Shah Jehan, was also coached

in Lahore. The legend lives on as her daughter Salma Agha, a bewitching

beauty, now features as a leading lady

Munnawar Sultana was yet another damsel from Punjab who shared equal honours

with Nargis for her performance in director S. U. Sunny's Babul

Bina Rai captured the imagination of millions when she first appeared

on the screen in 1950. Her Venus-like face became the cynosure of the

eyes of all those who saw her. Kishore Sahu featured her in Kalighata,

along with two other heroines, Asha Mathur and Indira Panchal. With the

release of this movie, Bina Rai was acclaimed as a beauty par excellence.

Later, her portrayal as Anarkali in the movie of the same name, established

her as the highest ranked film star in the Indian film world.

Undoubtedly, the greatest screen beauty who defied description and achieved

wide fame was the one and only Madhubala. Her mother came from Lahore

and her father from Peshawar. Her first picture as a heroine to go on

the sets was Daulat, opposite Janki Dass, author of this article, in 1948.

Produced and directed by Sohrab Modi, it was released in April 1949, though

Kidar Sharma's Neel Kamal starring Madhubala and Raj Kapoor was released

three months earlier. Then came Mahal, opposite Ashok Kumar. The movie

proved to be not only a landmark in Indian cinema, but also a cinegoer's

dream, and Madhubala was hailed as a dream-fairy.

Kamini Kaushal, a highly educated girl from the Punjab, swayed Indian

cinema with her talent, and she still plays interesting roles on the screen.

Bina Rai...........................................................Geeta

Bali

Geeta Bali (real name Harikirtan Kaur), introduced by the late

director Mazhar Khan, also created a new trend in the field of acting.

She belonged to a highly religious Sikh family. Her role in Bawre Nayan,

directed by Kidar Sharma, ensured her immortality in the annals of cinema.

Many other Sikh girls have subsequently dominated the Indian film world-Kuldeep

Kaur, the great 'vamp', and scintillating heroines like Neetu Singh,

Shoma Anand, Ranjeeta, Poonam Dhillon, Anita Raj, and Yogeeta

Bali, who is Geeta Bali's niece. Komila Wirk, Padmini Kapila, and

Rati Agnihotri are also working alongside other Punjabi actresses

like Indira Billi, Rama Vij and Rajni Sharma.

Kuldeep Kaur.......................Neetu

Singh............................................Yogita

Bali

Rati Agnihotri

In the world of music, there have been many nightingales

from Punjab. Shamshad Begum, Johra Ambalewali, Tamancha Jaan and Akhtari

Bai dominated the singing world of Indian cinema for many decades.

Then there was the great Suraiya, who not only reigned supreme as a leading