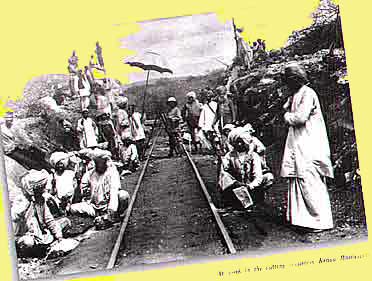

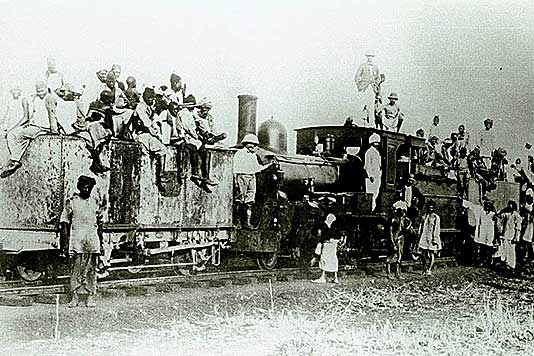

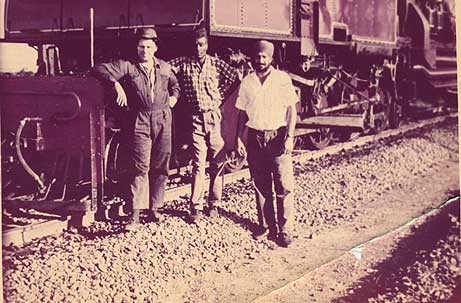

Workers on the Uganda Railways

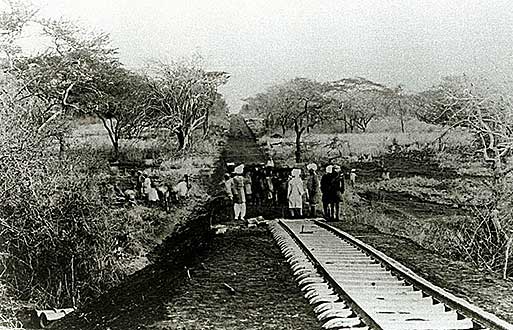

Workers on the Uganda railway line

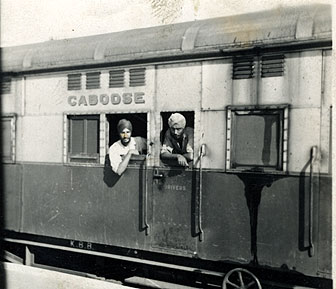

Train with railway employees & administrators. (top & bottom)

Train with railway employees & administrators. (top & bottom)

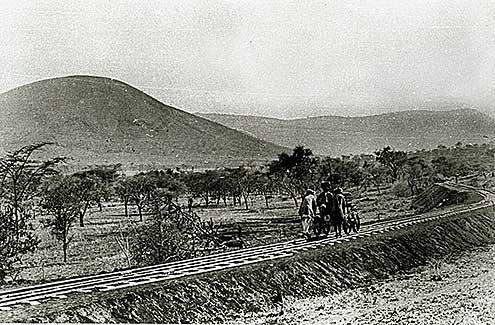

Railway track near Sultan Hamud

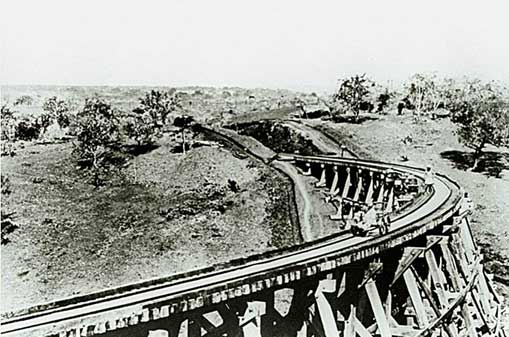

Railway bridge near Mazeras

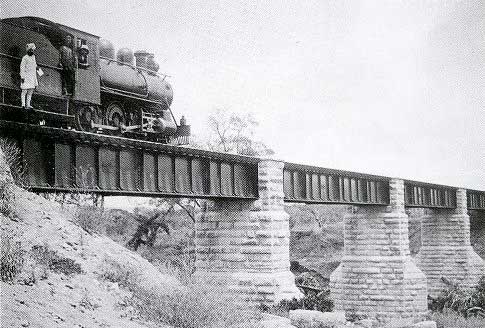

Crossing the Tsavo Bridge

Train near Mombasa about 1899 CE

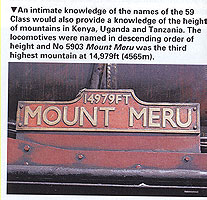

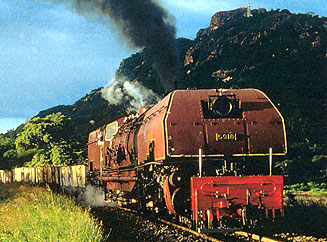

59 Class Garratt

EAST AFRICAN RAILWAYS

The 59 Class Beyer-Garratts were the largest

and most powerful locomotives ever built to operate on a

metre gauge railway. Designed to haul 1200 ton freight trains

over the steep east African mountains, they proved to be

as tough as the terrain they conquered.

The 59 Class Beyer-Garratt was the culmination of half a century of experience with articulated locomotives. They were designed and built to answer a desperate need: to haul heavy loads on the tight curves and steep gradients on some of the most difficult terrains in the world - the railways of east Africa.

Railways in east, west and southern Africa are mainly of metre and 3ft 6in gauge, though there are scattered lines of narrower gauge. Many of them were built at the end of the last century, during the grab for colonies, to exploit the natural resources of the continent by carrying them overland to the sea for export.

Building a railway

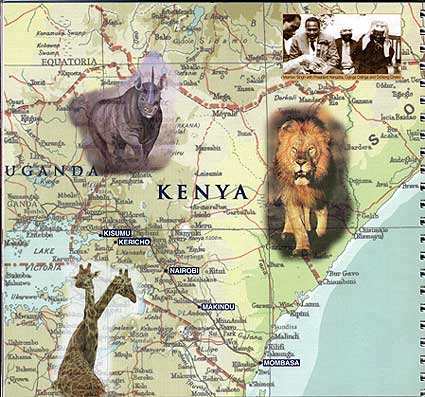

Kenya and Uganda, British protectorates since 1894/5, were dependent for their external trade on the port of Mombasa. To link the port with the hinterland a metre gauge railway was started in 1896, pushing north-west to reach the site of Nairobi in 1899. Nairobi was then a swampy plain devoid of habitation but destined to become Kenya's capital. The line was extended through mountainous country, to reach Lake Victoria -source of the White Nile - at Kisumu in 1901.

Various branches were built to open up the country and later to link with the system in Tanganyika (now Tanzania), previously a German colony. An extension to Kampala, the capital of Uganda, was not completed until 1931.

Nairobi is reached after a climb of 5750ft (1750m). Beyond, the line climbs a further 7700ft (2347m) to Uplands before descending 6000ft (1830m) to the floor of the Great Rift Valley. A final climb takes the line to its summit at Timbora, 9136ft (2784km) above sea level.

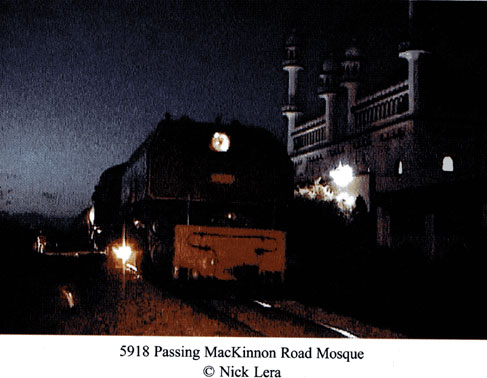

In Dec 1977 No.5918 Mount Gelai hauls the A38 goods eastwards from Samburu over steep gradient towards Mackinnon Road. The 59 class was well suited to hauling heavy loads. They had double the tractive effort of any locomotive employed on passenger service in the UK, where they were built in 1955.

In Dec 1977 No.5918 Mount Gelai hauls the A38 goods eastwards from Samburu over steep gradient towards Mackinnon Road. The 59 class was well suited to hauling heavy loads. They had double the tractive effort of any locomotive employed on passenger service in the UK, where they were built in 1955.

The terrain through which these lines were built called for heavy, sustained gradients and many curves. Consequently the railways' capacities were generally very limited. Much of the line was originally laid with 501b/yd rail, but by the late 1920s the Mombasa - Nairobi section had been relaid with new, heavier 801b/yd rail and this was subsequently extended to Kampala. This sort of railway and the Beyer-Garratt articulated locomotive became synonymous.

During the 329 miles journey between Mombasa & Nairobi there would usually be two stops for oil and six to eight stops for water. In the early 1960's No. 5901 'Mount Kenya' replenishes its water supply at Tsavo station.

Enter the Garratt

The Garratt's use of two engine units carrying fuel and water (water in the front, fuel and water in the rear) gave good flexibility on curves, while the boiler cradle was carried on pivots between them. This allowed a very large boiler to be mounted, its firebox completely unobstructed by wheels below it. The spread of weight over many axles - 14 or 16 in the case of the east African machines - kept individual axleloads down while providing ample adhesion and therefore power.

The first Beyer-Garratt, a small locomotive produced for work in Tasmania, Australasia, was built in 1909 and is now in the National Railway Museum, York. The articulated locomotive concept grew steadily into the South African giant built in 1930 which is now preserved in the Museum of Science and Industry, Manchester.

In 1926 the Kenya & Uganda Railway placed its first Garratt order, for four EC Class 4-8-2+2-8-4 wood-burning engines, which were used west of Nairobi and permitted to haul 457 tons on the 1 in 50 gradient. After a satisfactory two year trial the railway decided that its future lay with Garratts for main line work. Successive orders culminated in the majestic EC class 4-8-4+4-8-4 (later Class 57). These locomotives instituted through running between Nairobi and Kampala.

Different types of Garratt locomotives handled the given loads successfully until the early 1950s when, thanks to continuous traffic growth, the Mombasa - Nairobi section became a bottleneck with exports and imports being seriously delayed. By now the track here had been relaid with 951b/yd rail and was already supporting the 17'/2 ton axleload of the EA class 2-8-2s. Careful study of locomotive forces acting on the track showed that axleload up to 21 tons could be borne, provided that the weight tapered off at each end of the locomotive.

Production of the 59s

In 1954 the UK locomotive builder, Beyer-Peacock, was asked to produce a new and much bigger 4-8-2+2-8-4 Garratt, capable of hauling 1200 ton trains on the 1 in 66 gradients and with the enormous tractive effort of 83,3501b. The 34 engines of the 59 Class were delivered in 1955 in an attractive livery of dark red lined out in yellow. Most were given names of mountains in east Africa.

Everything possible was built into the engines to give sustained power and high mileage between overhauls. They had bar frames machined from 4V2in thick slabs and roller bearings on all axles and big ends. The boiler was enormous, with a barrel diameter of 7ft 6in - 6in larger than the LNER's solitary 2-8-0+0-8-2 Garratt - and was oil fired. If they had burned coal (and provision was made to fit a mechanical stoker if a change to coal was ever necessary), the grate would have had an area of 72sq ft - half as much again as a Bulleid Merchant Navy Pacific. The front and rear tanks were of Beyer-Peacock's later streamlined form and a power reverser was provided. Air braking for engine and train was standard.

The main work of the 59 class was hauling trains of imports & exports between the port of Mombasa and the towns of Nairobi ans Kampala. While the eastbound trains contained exports of tea, coffee and agricultural produce, the westbound trains included imports of farm machinery, fuel and consumer imports. On 21 December 1977, No. 5912 'Mount Oldeani' toils uphill with a westbound train of imports to Nairobi.

An interesting feature built into the 59s, like all engines for east Africa since pre-war days, was ease of conversion to 3ft 6in gauge if there was a link with the systems in Rhodesia (now Zambiaand Zimbabwe) and South Africa. All wheel rims were just over one inch wider than normal, so that new tyres could be shrunk on to suit the wider gauge.

On test the specified 1200 ton load was handled comfortably and even exceeded. Such was the impact of these remarkable locomotives and their heavier trains (1400 tons permitted between the coast and Nairobi) that within 12 months the main line operation was back to normal and congestion at Mombasa was at an end.

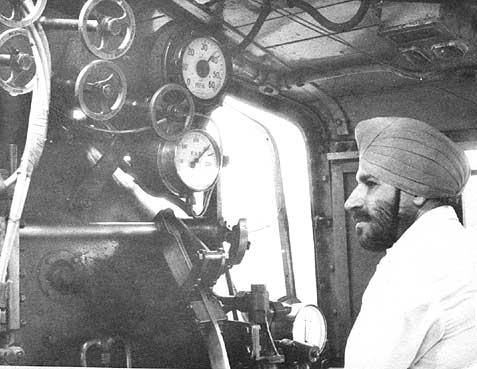

Working days

During normal service the 59s were manned by two regular crews on a caboose basis, one working and one resting in a van with sleeping accommodation, changing over at eight hour intervals. The engines were kept very clean and the cabs were polished and immaculate.

The performance of the locomotives, if not their appearance, was further enhanced between 1959 and 1967 by the fitting of Giesl ejectors in place of the original single chimneys. This led to separate timings for single chimney and Giesl Garratts, enabling, for instance, several hours to be saved in running between Kampala and the summit at Timboroa.

No. 5918 'Mount Gelai' shows off its lines in the evening sun on 19/12/1977. An advantage of the Garrats was the absence of wheels under the centre section.

But, as elsewhere, the diesel locomotive was in the ascendant, even though two were required to do the work of one Garratt. Withdrawal started in 1973 and the fires were doused on the last 59 Class in 1980. Two were saved from the torch and restored to working order.

It was also the end for the locomotive building firm of Beyer-Peacock. In the late 1950s the demand for steam engines collapsed worldwide and the firm's entry into diesel and electric traction came too late. The works closed in 1966. (Article courtesy 'The World of Trains' )

Following Excerpt taken from 'Steam Safari' written by Colin Garratt....

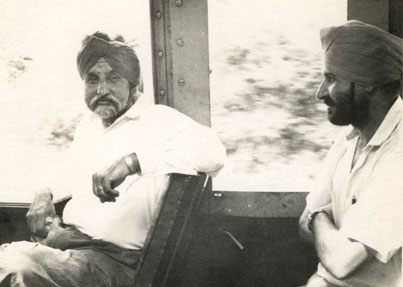

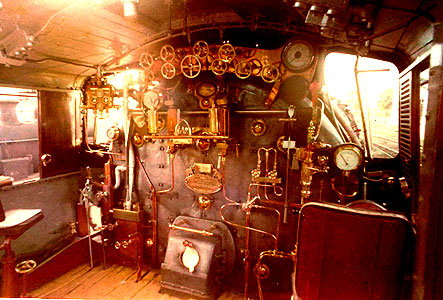

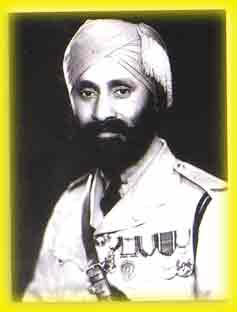

Many 59s have Sikh drivers, the most famous example being 5918, Mount Gelai- a brass plate from this engine's cab is sketched below. The overall condition of Mount Gelaiis possibly unrivalled anywhere in the world today. Her cab interior is more akin to a Sikh Temple than a locomotive footplate for its boiler face abounds in polished brasswork, embellished with mirrors, clocks, silver buckets and a linoleum floor. The crews are known throughout East Africa as the 'Magnificent Foursome' and so well do they care for their steed, that a failure is almost unknown and no breakdown in traffic has ever been recorded against this engine since they took over ten years ago. She has the highest mileage record between shoppings and on several occasions 5918 has been taken to Nairobi Works for overhaul as a matter of policy, rather than for any recognisable necessity!

Twenty 'Mountains' are allocated to Nairobi, whilst the remaining fourteen belong to Mombasa. The Mombasa engines can be easily picked out by their black backed number and name plates, compared with Nairobi's red ones. How these engines are revered by crews and engineers alike; little inducement being needed to evoke an enthusiastic discussion. The following fragment from my conversation with a locomotive fitter at Mombasa will convey the spirit - such were his phrases. . . . 'Yes, 5931 is the cleanest, but then she's only been out of shops a month — and with the official maroon livery too. 5913 is chocolate brown - she belongs to Nairobi. They say that 5912 is the best - that's the one with wing plates on the smokebox, I've heard tales that she will go up Miritini bank with a full load at fifteen per cent cut off- but I doubt it. 5906 has a cracked frame and one of her drivers is acting day foreman here whilst his engine is in Nairobi shops. The one that always gets the limelight is 5918, but you know about her. I agree, the names are impressive, personally I like 01 'Donya Sabuk -she's one of ours, we have her in the sick bay at present, you've possibly seen her. Did you hear about 5917 hitting a herd of elephants last week?' I hope such lyrical phrases as these convey something of the spirit; to me they almost constitute a style of free form poetry. Here is the 59 Class:

- 5901Mount Kenya 5918 Mount Gelai

- 5902Ruwenzori Mountains 5919 Mount Lengai

- 5903Mount Mem 5920 Mount Mbeya

- 5904Mount Elgon 5921 Mount Nyiru

- 5905Mount Muhavma 5922 Mount Blac.kett

- 5906Mount Sattima 5923 Mount Longonot

- 5907Mount Kinangop 5924 Mount Eburu

- 5908Mount Loolmalasin 5925 Mount Monduli

- 5909Mount Mgahinga 5926 Mount Kimhandu

- 5910Mount Hanang 5927 Mount Tinderet

- 5911Mount Sekerri 5928 Mount Kilimanjaro

- 5912Mount Oldeani 5929 Mount Longido

- 5913Mount Debasien 5930 Mount Shengena

- 5914Mount Londiani 5931 Uluguru Mountains

- 5915Mount Mtorwi 5932 01 'Donya Sabuk

- 5916Mount Rungwe 5933 Mount Suswa 5917Mount Kitumbeine 5934 Menengai Crater

......................................

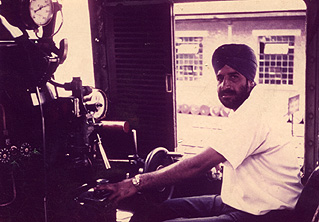

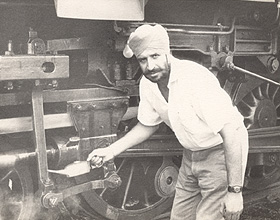

Old Photographs sent by Locomotive DRIVER -Karnail Singh of Nairobi, who was stationed at Tanga Loco shed.

Mount Kilimanjaro

Mt. Kilimanjaro

Driver Karnail Singh steering the Kilimanjaro

Driver Karnail Singh oiling parts of Mount Kilimanjaro

The inside of the Mt. Kilimanjaro

Karnail & another driver Avtar Singh in their caboose (1967)

At a station

In this instance the Kilimanjaro was just saved from being derailed as the signalman had changed tracks without realising that the train was still on the other track.

Karnail with an English Driver & African Fireman

Karnail with another co-driver Pritam Singh Ahluwalia

Driver Kirpal Singh with his train near Kibwezi

Kirpal's train (photo courtesy Kevin Patience)

Kirpal's train at Changamwe (photo courtesy Kevin Patience)

Inside the above train (photo courtesy Kevin Patience)

Students with teachers at a Railways training School (any recognitions?)

Driver Joginder Singh with his African Fireman (courtesy Railway Archives,Nairobi)

Driver Joginder Singh with his African Fireman (courtesy Railway Archives,Nairobi)

Nakuru Railway Station - a staff party - Bakshish Singh Kalsi addressing 1948 (photo courtesy Dhanwant Mundae)

Locomotive driver Gurdial Singh at Mombasa ready to take train to Nairobi. (photo courtesy Dhanwant Mundae)

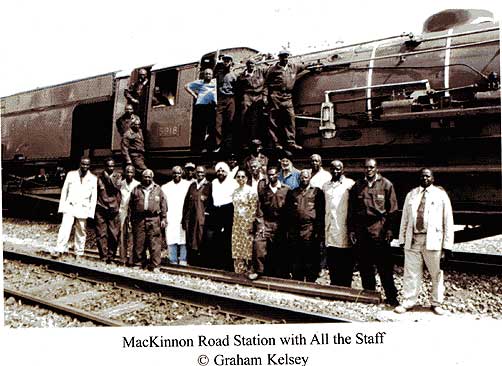

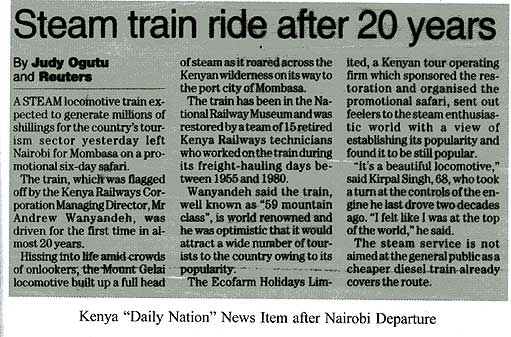

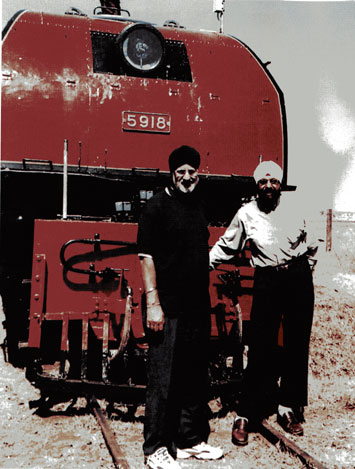

A very historic journey took place in Kenya when the original driver of the Locomotive 5918 Kirpal Singh (in white turban), who was the driver of this steam engine 'Mount Gelai' was reunited with it in November 2001 to embark on this exceptional journey. An account of this journey has been written by Charan Singh Kundi (in black turban)who accompanied Kirpal on this occasion. The book 'Steam Safari with East African Railways' is a first hand narration of this journey.

Charan & Kirpal at the end of their historic journey pose with their partner 5918. Photo courtesy Nick Lera (Steam Safari)

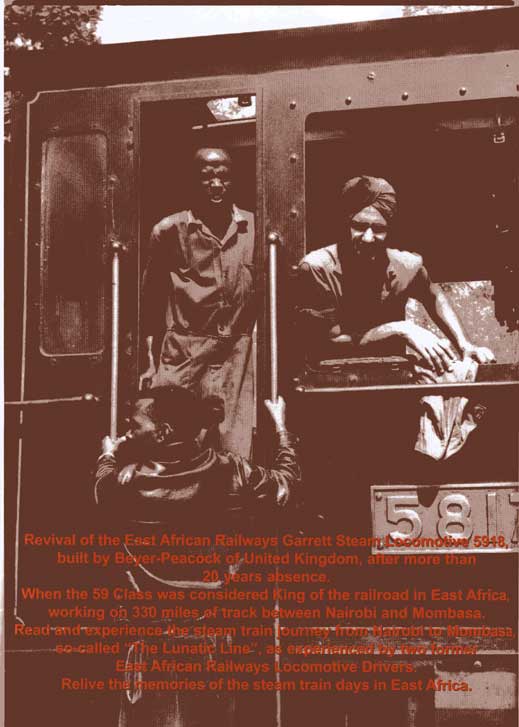

Charan Singh Kundi aboard his train bound for Kampala from Eldoret.

Charan with his firemen on a trip from Eldoret to Kampala with 5817 in 1963

Driver Harjit Singh Mangat (sent by Baljinder Kahlon)

A brief account of the sad demise of Harjit Singh Mangat as sent by driver Charan Singh (3above)

I was based at Nairobi when I joined as a fireman in 1956, most of my trips were to Mombasa until I became a driver in 1960.

I was in contact with another driver Joginder Singh Gill who was at Nakuru andI think he came on transfer from Tabora in 1959 just after Harjit 's accident.

I have spoken to Joginder Singh, he says Harjit Singh Died in an accident, when his train

overshot on the way from Nakuru to Kisumu, at Fort Tiernon station. There is steep down

gradient from Mau Summit station to Mohoroney station.

I have driven on that section as well just before coming to UK.

On those days we had to apply retainers to some wagons so that there was continued

braking on the train, unfortunately it seems his train lost all braking pressure and the train

picked up speed and derailed.

Regards,

Charan

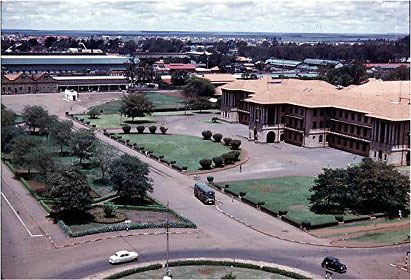

Railway head quarters Nairobi

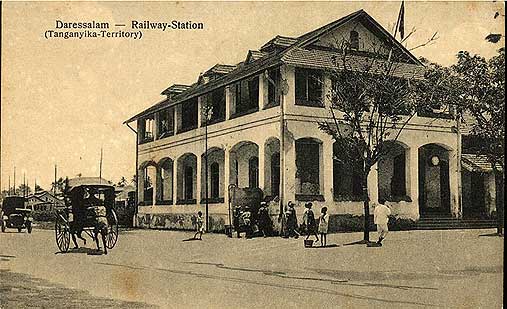

Dar-es-Salaam Railway Station 1930's

Railway Hotel Dar-es Salaam

Nairobi Railway Station

The OLD railway walking bridge from the Nairobi Railway station to the other side near Gurdwara Railway landhies. (see the barber shop on the right!! -want a shave?)

The Uganda Mail crossing the Nile River

Between Nakuru & Kisumu a train trundeles along.

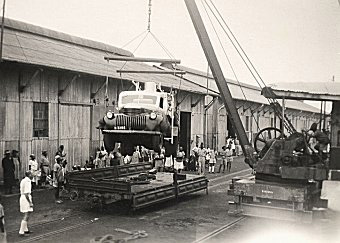

Loading a truck at Mwanza railway station (Tanganyika Railways)

A 29 class train with Mount Longonot in the background.

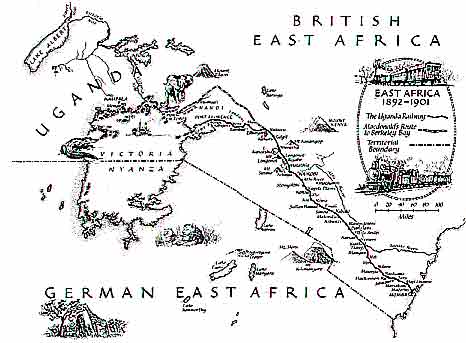

The Uganda Railways

An appeal for construction-workers was made to India in 1896 its response 'was not enthusiastic because of unfortunate experiences with indentured labour in other parts of the Empire', as stated in an official report by Sir John Kirk, one of the founders of the Imperial British East Africa Company, and Vice-Chairman of the Railway Committee in the 1890's. Subsequently, 'the government of India agreed to provide labour only on condition that every emigrant, at the end of three years service, would be afforded the threefold option of renewing his contract, returning to his home village with all expenses paid, or remaining in East Africa as a settler and forfeiting his return passage.'

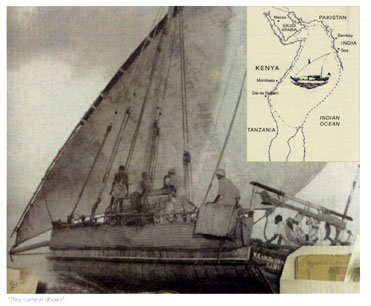

Predominantly Punjabi Muslims, but also many Sikhs and Hindus were recruited for the actual construction. They came mainly through Karachi, and some through Bombay. A few Sindhis as well came via Karachi. As a point of interest, during the same period workers were leaving ports in western India such a Broach, Surat and Kolaba for South and Central Africa.

Very few brought their families to East Africa, but some brought along their servants. A few single men, usually seniors ('headmen') took wives from the Swahili camp followers. They could afford this luxury somewhat better than the labourers, who were paid a minimum wage of only fifteen shillings per month.

The reader may find the following points of interest:

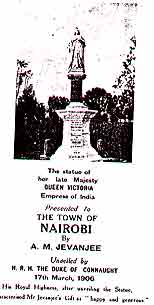

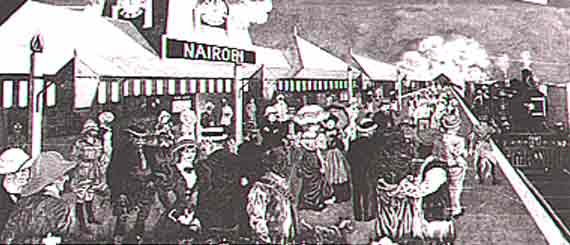

- The laying of the first rail commenced in Mombasa on

August 5, 1896 - On June 5, 1899 the railway reached mile 326, a little

over halfway to Kisumu. It was a swampy area that the

Masai called 'the place of cold waters': NAIROBI.

On December 19, 1901 it reached mile 582 (931 km), at the shores of Lake Victoria—Port Florence then, Kisumu now.

1 A total of 34,400 Asians worked on the construction of the Mombasa—Kisumu segment

By one authoritative estimate 51% of the Asian workers returned home at the end of their contracts, 20% returned during their contracts due to disease or injury, 8% died on the job, and the remaining 21% (around 7000 men) did not take their tickets for the return journey home from the employer, presumably most of them deciding to stay back in Kenya.

"The railway could not have been finished with (local) labour under 20 years" Sir John Kirk is recorded as having said in the Report of the Committee on Emigration. Mervyn E Hill, the official historian of the Railway went even further in his forthright comment: "Without the aid of Indian labour, artisans and subordinate staff, the railway would not have been built"!

With the Asians' help it was built in less than five years. (And yet for over 30 years Asians were not allowed, by law, to travel first class on the railway they had built at such high personal cost, 28 of their colleagues having been devoured by the lions of Tsavo—a total of 2,493 having perished at the rate of 4 dead per mile of track laid).

In 1921, the Uganda stretch of the Railway started at Nakuru, to be linked to Kampala in Uganda. In fact eight years earlier, in 1913, the Busoga Railway, connecting Jinja on the shores of Lake Victoria to Namsagali on Lake Kioga, had already come into existence in Uganda! (Busoga Railway was linked to the Kenya line in 1927, four years before the completion of the Eldoret-Kampala stretch)

In 1924, the Uganda Railway reached Eldoret.

It finally reached Kampala in 1931, delayed somewhat by the need to bridge it over the Nile at Jinja.

(courtesy ‘Real African Phantom by Khalid Malik)

=======================================================

‘The Iron Snake’

by

Ronald Hardy

Publishers

Collins St James Place, London 1965

*

“An iron snake will cross from the lake of salt to the lands of the Great Lake”

Ancient Kikuyu prophecy

*

“The railway is the beginning of all history in Kenya”

Sir Edward Grigg

*

“ The two iron streaks of rail that wind away among the hills and foliage of Mombasa Island do not break their smooth monotony until, after piercing Equatorial forests, stretching across immense prairies, and climbing almost to the level of the European snow-line, they pause upon the edges of the Great Lake”

Winston Churchill ‘My Africa Journey’

*

“The line was 582 miles long. It began on 5 August 1896 on the Mombasa mainland and it reached Port Florence on Lake Victoria on 19 December 1901. The capital cost was £5,502,592. The cost in lives was 2,493 Asians and 5 Whites. 31,983 coolies were imported from India. Of these 6,454 were invalidated back to India and 16,312 were repatriated or dismissed. 6,724 Indians remained in East Africa to become the main progenitors of the present Asian population. 43 stations were built and 22 construction locomotives were worn out. The bridging included the Salisbury Bridge

(joining the island of Mombasa to the mainland) of 21 spans of 60-foot girders, 35 viaducts of the Kikuyu and the Mau Escarpments; and 1,280smaller bridges and culverts.”

*

Cost per mile: £ 9,454

Number of men killed per mile: 4.30 men (Asians and Whites)

Number of men imported per mile: 55 men

Number of men invalidated per mile: 11 men

Number of Indians per mile settled in East Africa: 11.5 men

(Sent by Rohina Grewal)

===============================================

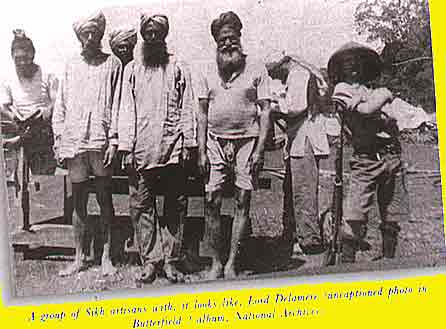

THE SIKHS IN EAST AFRICA

The history of the Sikhs of East Africa begins with the Railway - though detachments of Sikh Regiments had seen service in certain parts of East Africa in previous years.

The Sikhs who were brought over from India to build the old Uganda Railways were skilled workmen - carpenters, blacksmiths and masons. They were quick to adept themselves to the specialised requirements of the Railways and many became fitters and turners and boiler-makers.

The story of the construction of the Uganda Railway is well known in history with many books written about it -'Man Eaters of Tsavo' is one of the books which narrates the genuine fear of the labourers, who gave their lives in the jungles of Kenya while building the Railways. The early settlers had to face these marauding lions that were a constant threat to their lives. It is only necessary to mention that these famous man-eating lions seem to have had a great partiality for Sikhs as their staple diet. Anyway, these stout sons of the Punjab continued to push the twin lines of steel forward, lions and leopards notwithstanding.

These early Sikhs were soon joined by their educated brothers. There was no department of the pioneering Railway without its Sikhs. A number of policemen, ranging from inspectors to constables, were also sent from India to become the vital instrument of maintaining law and order. They remained in the country for several years.

Many, but not all, of the original Sikh arrivals returned to India to be replaced and augmented by others who came of their own volition. Their skills and industry were always in great demand.

The Sikhs penetrated into every nook and corner of East Africa to erect the buildings and to build the roads; to undertake general maintenance work on the farms; to serve in the offices and to assume charge of the hospitals.

The manner in which the Sikhs increased their usefulness to Kenya is a saga of resource and initiative and perseverance.

They undertook with confidence any type of work, which required skill and industry. They became highly successful farmers. They responded magnificently to the growing needs of the country by improving and diversifying their capabilities. They became contractors and furniture makers.

SIKHS IN KENYA

During the latter half of the last century, a large number of migrantsrom the Indian sub-continent flocked to the shores of East Africa in dhows under considerable hardship. It was not until 1895 that

there was an intensive Sikh presence in the country when a

contingent was brought to Mombasa in order to police the

Uganda railway as well as the caravan

routes into the hinterland. After which,

the Sikh military contact and presence

intensified with Sikh soldiers being

brought to deal with the Kabaka's

uprising in 1898 in Uganda and other

similar excursions. However, it was

the building of the Uganda railway,

which witnessed a large influx of Sikhs

into Kenya with most arriving as

indentured workers.

While a number of Sikhs opted to return to their homeland when the railway was completed the majority remained in Kenya, sparking a wave of free immigrants from all walks of life who brought with them particular skills which have since been linked inextricably with Kenya's subsequent development.

As Sikhs began to settle in their adopted country a sense of community was imbued by the building of gurdwaras in all areas of the country where Sikhs settled. As the community prospered it turned its attention to its youth and in turn several Khalsa schools were built to aid the education process of the budding community. The schools have from their inception been an important point of contact and service for the wider community as children from all races are encouraged to attend. The schools have also served as a rallying and unifying point for the entire Sikh community. Sikhs who traditionally worked as farmers, crafts-people and artisans ensured that their children availed themselves of the educational opportunities and within a generation Sikhs came to occupy positions in all walks of life, from skilled crafts-people, independent entrepreneurs to professionals.

For nearly a century Sikhs have lived in this country with a unique mix of cultures and in that time Sikhs have increasingly turned their attention to the needs of the wider community and their role as citizens of the country. To that end, they have heeded Guru

Nanak's call for service and are at the forefront of providing support to community organisations.

Sikhs have been regular contributors to Harambee projects throughout the country. They have established medical facilities including hospitals, clinics and dispensaries to serve the wider community. Hence, it is not surprising that Sikhs are viewed as an integral part of the Kenyan nation.

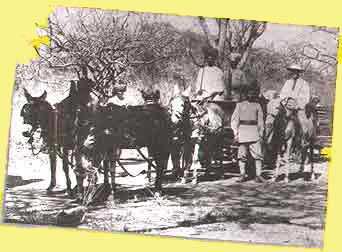

BULLOCK CARTS

Long before the motoring era, they played an invaluable part, along with the other Punjabis in solving the transport problem of the country. They built and operated Indian style bullock carts.

When the motorcar and the motor-truck began to trickle in, the Sikhs converted themselves into mechanics and engineers. They began to own garages and engineering workshops. Anything that was tough and challenging attracted the Sikhs.

With every succeeding year the Sikhs adopted a steadily rising standard of living; they gave the best possible education to their children, and they invested by far the greatest proportion of their earnings within the country.

The Sikhs entered all the professions, nor did they neglect the realm of industry, their speciality being saw milling.

In the Police, the Civil Service, in the commercial establishments, the educational and medical institutions, in the factories and workshops, the Sikhs came to play a very important role indeed.

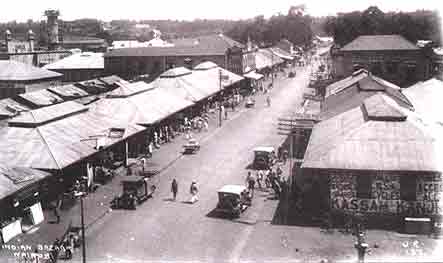

Nairobi, the capitol of Kenya boasted the majority of the Sikhs. Although the turban and the beard was the distinctive emblem of them all, they presented contrasts of every conceivable description, which of course was one of the healthiest sign of an alive and progressive community.

Among them were men of real learning and near-illiterates… though these latter were virtually extinct. They contained men of great refinement and others whose rusticity faithfully reflected their occupations.

There were, however, no acute extremes in the local Sikhs in wealth. Throughout East Africa, the Sikhs of substantial wealth were very few indeed. It was a community of the middle-income group, because instances of extreme poverty were also scarce.

During the initial 60 years or so of the last millennium, the Sikhs built nearly 40 Gurdwaras or temples in various towns of East Africa, a truly remarkable achievement. They managed a dozen 'aided' schools of which one is in Nairobi and was amongst the largest in the whole country.

These schools were open to all races; the Sikh clubs which existed in most of the major towns had throughout been important venues of inter-racial social functions and had always admitted non-Sikhs as members.

From the earliest days, the Sikhs played a very prominent part in many aspects of sport, both as players and as administrators and organisers.

Sikh women's organisations were attached to every Sikh Temple. They held their own separate congregations but they also participated in terms of complete equality with the main congregations as well.

There were several Sikh study circles, libraries, and young men's associations' also A Sikh Missionary Society, which published Sikh literature on many occasions.

The public life of Kenya had been well served by the Sikhs. They had been Members of the Legislative Council and of all the municipal councils. They had taken part in numerous other bodies and commissions and committees.

The Sikh Community of Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania was one of the largest outside India and is proud of its record.

We present some early exploits of the Sikhs in Kenya, who were subjected to lots of hard work and fear of the 'Man-Eating' lions.

A

NARROW ESCAPE

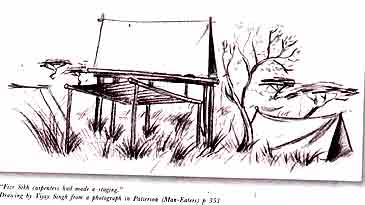

From In the Grip of the Nyika by. H. Patterson

(pp 6-7)

Five Sikh carpenters had made a staging some eight feet high and on this had pitched their tent, where they slept in peace and, as they thought, in safety. Every night they gained access to their airy abode by means of a moveable ladder, and they took the precaution, Robinson Crusoe-like, of pulling it up into their castle imme-diately after nightfall. I had already warned these men that their perch was not nearly high enough, and told them that they would be much safer on the water-tank or in trees, until the iron huts which I was then building for their protection could be got ready. They did not wish to move, however, and Natha Singh, the leader of the party, assured me that they felt quite safe so high up; besides, was not 'Khuda' (God) all-powerful? It seems that 'Khuda' was indeed looking after them. One night, contrary to their usual custom, they carelessly left part of the ladder projecting a little way beyond the end of the staging; a hungry Man-Eater on the prowl observed this, and thinking that he could not find a meal more conveniently elsewhere, determined to try how a carpenter tasted. Calculating his spring, he leaped lightly on to the projecting ladder, which, unfortunately for him, instantly tipped up and toppled over, both falling heavily to the ground. No doubt the ladder gave him a good blow when it struck him, for he fled at once without attempting to touch the men, who, thoroughly terrified by the tearing of their tent caused by the tipping up of the ladder and believing that the lion was upon them, jumped from the staging in all directions and with terror-stricken cries raced for their lives to the nearest trees. Fortunately no one was hurt, but after this the staging was deserted for the more secure fastness of the top of a masonry pier rising out of the riverbed.

From interview with late Indar Singh Gill,Nairobi

I'm 90 now and I can't remember everything now, but I'll tell you what

I can about my background in India and my first years in Africa.

Our family

had a farm in the village of Jun dali, in the Ludhiana District of the Punjab.

We were farmers; Jats - all Gills were traditionally farmers; Gills are what you

could call a clan of Jats. My mother died when I was just five hours old; when

I was a baby I was brought up by her brother and his wife.

I was sent to the best school in the area, a school in Ludhiana run by the Arya Samaj. No, it didn't matter that the Arya Samajists are very staunch Hindus and we Jats are Sikhs; my father had good relations with the Arya Samaj people. He did not care what religion anyone belonged to; he said that the only thing important in religion is to believe in God, to be honest and to be good to people.

I completed Standard 8 in that school and then I returned to my father who had remarried. My little half-brothers were going to a private school in our village. As I had finished my schooling I used to take them to school in the mornings and collect them in the afternoon. One day the headmaster, knowing that I had learned English, asked me what I was doing. I said, "Nothing." So he gave me a job teaching in his school, with a salary of 13 rupees a month. It was a small school, built of bricks with about 100 boys.

We landed at Mombasa and went up to Nairobi by train. My companion took me to my uncle who was very surprised to see me. But he welcomed me and got me into the Railway School as a trainee. I lived with my uncle. As he was here with his wife and their children, three sons and a daughter, he was renting a house so there was room for me.

After finishing my training I was taken on as a telegraphist @ sh 20/- a month.

I was very happy that I had come, for that was much better than being a teacher earning

13 rupees. I worked for the Railway for over forty years, up until 1963.

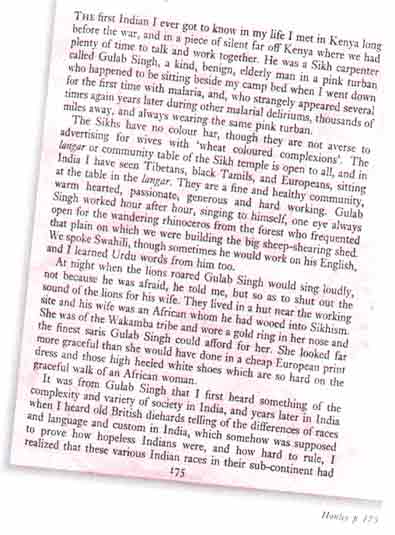

I was sent to different stations along the line in Kenya: Njoro, Molo, Muhoroni, Kibos, Kipikori, Kisumu. There were a lot of European settlers at Njoro and Mob. Lord Delamere was at Njoro. Yes, we knew each other. As I spoke English I got to know the Settlers. They'd come to me for booking wagons for transporting their produce out and bringing supplies in. We got along very well. That was a wonderful job, working with the Settlers. After four or five years I was promoted to Stationmaster grade @ sh 250/- a month. My Punjabi colleagues all called me 'Bauji' - sort of a title of respect for government officials.

I saw that things were good, so when I went home on leave in 1925 I brought my wife Bachan Kaur back with me (we'd been married when we were 12, but had not been allowed to see each other again until we were 19, just before I left home). Then in 1926 I was transferred to Uganda. I began doing other business on the side

I went into saw milling and had cotton ginneries. I settled in Jinja and built a fine house, which I called 'Lakeview'. The rest is well known: I became one of the three multi-millionaires of Jinja, along with Mehta and Madhvani (both of whom made their money in sugar). And then I was one of the thousands of Asians thrown out by Idi Amin in 1972.

Fortunately I had kept ties in Kenya. I'd laid the foundations stones of both the old and the new Singh Sabha temples in Nairobi, and in 1948-50 I had built Gill House, the first 5-storey building in town - a skyscraper in those days, which I rented to the colonial government for offices. So in 1972 I came back to Kenya where I had started my career as Bauji'. It was all because of my Uncle Nahar Singh that I am what I am today. I still keep his portrait in my office. Yes, though I am 90 years old I still go to the office every day.

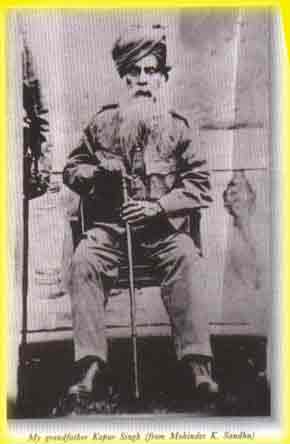

(Mohinder Kaur Sandhu, Nairobi)

My grandfather Kapur Singh was the first Indian Inspector of Police here. He was originally from the village of Gagobuha, near Amritsar in India and he joined the police force there. First he was posted to Baluchistan, and then in 1895 he was seconded from India to work with the Kenya Police.

Kapur Singh became greatly respected, not only because of his high rank in the police force but also in his community. He had the honour of laying the foundation stone of the first Sikh temple in Nairobi. Although the building, the Singh Sabha Gurdwara, has been greatly altered, the original plaque with his name is still there. He also laid the foundation stones of mosques in Nakuru, Kisumu and Mombasa. That shows not only how respected he was but also how good inter-communal relationships were in those days.

From interviews with Mohinder K Sandhu and Bhupinder S. Sandhu, Nairobi

My grandfather Kapur Singh was already

married when he came to Kenya. His wife stayed in Gagobuha, except for one brief

visit here. They had three sons and a daughter. The daughter died, one son stayed

in India, but two sons followed their father to Kenya and also joined the

Police. One was Laxman Singh and the other was my father Satbachan Singh (left)

, who

Was born in 1900.

In his career as a police officer my father

Satbachan Singh moved around lot as he was transferred from place to place. Much

of the time he was in Nairobi. In the early days Nairobi was very wild, covered

with bush. When he went on his rounds he would come hack covered with ticks. Sometimes

he encountered lions. He was posted up to Cherangani, and out at Tigoni too, in

Settler days.

Satbachan Singh was not at all what one thinks of as a typical policeman. He was a very gentle man. He never raised his voice, never got angry.

Previously, sometime in the late 20s I think, he had been posted to Voi to halt the slaughter of elephants for their ivory. My father was very fond of nature (he later became a founder of the Wildlife Society) and was angry about all the poaching. He walked miles and miles in the forests around Voi until he finally got to the source of the poaching and captured the man responsible for the entire killing and smuggling. My father tied the man to a tree and threatened to burn him unless he told where the ivory was hidden. The poacher of course told, and all the ivory was recovered. My father's boss was so pleased that he told my father, 'Pick out the best tusk as your reward for controlling the poaching'.

Perhaps the reason my father was so fond of nature and the outdoors was that his family was farming in India. He bought a farm here, 400 acres of land at the foothills of the Nandi Hills near Miwani. My uncle Laxman Singh retired from the Police to run the farm and my father spent as much time as he could there. I stayed there when I was a little girl, four and five years old, before I had to go to school, the Jndian Primary School in Nairobi.

Because I was the youngest I was my father's pet and I remember him taking my mother and me for walks around the farm. Most of the farm was planted with sugarcane but he also had pedigree cows of which he was very proud, and pigs. He was the first Indian to whom the Colonial Government gave a license to keep and breed pigs. He also had a fine orchard with a lot of fruit trees he imported from South Africa, including seedless oranges. He kept horses there, for he loved riding and was a very good horseman. (But he never taught me to ride.) He had a couple of horses on the farm, brown ones, and he kept one for his own use in Nairobi too. He was also good at shooting.

Even when we were living in town, my father liked to be outdoors. He was very fond of picnics and every Sunday he'd take us all on an outing somewhere. He was a strict parent (it was our mother who was the soft one) and a very serious person (he always dressed very well, in jacket and trousers when not in uniform). But he also had a good sense of humour and liked to relax with his friends. He had close friends in all the communities, Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims, and Europeans too (he was a good friend of Dr. Leakey, the old Leakey who was a naturalist). He was usually very busy with his CID work all day, but in the evenings his friends would come around and visit him. Often he'd have visitors from India, especially people wanting his help in getting settled here.

Once my father resigned from the police force for a day. There had been theft of money at the Norfolk hotel. Fingerprints were taken and suspicion pointed to a European woman. When my father was driving her to the police station she became terribly upset. He assured her she would not go to jail. But when she was searched, the money was found in her panties. My father let her go anyway; as he said, he'd promised her she would not go to jail, and he could not go back on his word. When the Commissioner found out he was furious. My father, knowing that according to regulations he should have charged her, submitted his resignation. The next day the Commissioner came to him and said, 'Forget your resignation. You're on duty.'

My father retired in 1945/46 but then was recalled because of the Emergency. He left the management of the farm in the hands of a nephew; a son of his brother Laxman Singh. (Both his own sons were otherwise occupied: the elder, who worked in the post office, was also a police reservist, and the younger was in a special branch of the police.) Things did not go well and in 1968 he sold out and returned to Gagobuha. (My mother had passed away in 1948.) He came back for a visit in 1976. While he was here he attended the cremation of a very close friend Mistri Mangal Singh and there encountered Mitchell, the Assistant Commissioner of Police. My father asked, Do you remember me?' and Mitchell said, 'Of course. You're the oldest police officer in Kenya.'

HYPNOTIC COP

From

interviews with Bhupinder S Sandhu, Nairobi

In 1954 I married Mohinder

Kaur, the only daughter of Satbachan Singh, and came to live in Kenya. I got to

know my father-in-law very well, and found him a fascinating person for as well

as being a strict police officer, Satbachan Singh was deeply interested in spiritualism.

He had been greatly influenced by a man named Dunichand, one of Satbachan Singh's

teachers in school here in Nairobi. Dunichand was like a guru to Satbachan Singh.

Dunichand was very strict about such things as drinking and although Satbachan

Singh was very fond of good food (his wife was an excellent cook), he never took

a drink of alcohol in his life.

Satbachan Singh developed an ability to hypnotise

people. He didn't learn that from Dunichand. Maybe he had a teacher or perhaps

he learned from books. (He gave me several lessons but we had to give it up because

I drink, and you cannot take alcohol at all if you want to be able to hypnotise.)

Although he gave one or two shows on hypnotism, Satbachan Singh didn't use his

skill for fun, or for getting people to confess things in police cases. He used

it only for healing people. He never advertised it in any way but people came

to know of it and if someone came to him whom he thought he could help he would

do what he could.

I can vouch for some of his cures, for I saw them myself.

I saw him hypnotise and cure an Asian lady who was so crippled she was bedridden.

After his treatment she was able to walk again, with crutches. He cured another

woman I know of migraine headaches. He cured one of his servants who had crippled

hands. It was not easy; he would have to prepare by magnetising himself when he

had a patient to treat. He would then be able to transfer his suggestions from

himself to his patient through passes.

Satbachan Singh could communicate with

spirits. He would sometimes hypnotise a person and use that person as a medium.

He said there were a few of his African sergeants he could hypnotise.

Satbachan

Singh was an active member of the Theosophical Society. He was also a Freemason.

I think this and his hypnotism were like vents from the strain of being a high-ranking

police officer.

A TOWER OF STRENGTH

From 'Cuckoo in Kenya' By WR. Foran (pp 102-6 passim)

On the morning of May

16, 1904, I duly reported for duty at Ewart's office in the small row of shanties

facing the Public Gardens. I expected to be trained in the work under his personal

tutelage, but such hopes were rudely shattered immediately. He posted me to the

charge of the Nairobi police station, with instructions to take over my new duties

at once. I was to relieve Besant Singh, the Sikh Inspector, who would serve under

my command henceforth. Once more I emphasised my complete ig-norance of police

work, the laws of the land, and the Swahili or Hindustani languages. This did

not seem to worry Ewart.

Presently I walked diffidently into Nairobi's police-station,

introduced myself to the stalwart, black-bearded Besant Singh, and acknowledged

the salutes of my new subordinates. The Sikh Inspector accepted being deposed

with a friendly smile, which I thought did him immense credit, and seemed anxious

to prove helpful to the stranger within their midst.

The staff of the police

station consisted entirely of Indian and African police. All the records were

kept in Urdu by the Indian police-writers; and Besant Singh seemed the

only man of'the staff with more than a superficial knowledge of English. The handicap

confronting me made my heart sink into the pit of my stomach.

I felt like

a lamb among wolves.

Still more agitated now than when I entered the police

station, I transferred my interest to a hefty stack of police files and criminal

investigation reports. Besant Singh had quietly placed them on the table, speaking

in rapid and fluent Hindustani far too fluent for me to understand all he said.

I glanced up sheepishly at the smiling, watchful Sikh Inspector, seeking inspiration

from his non-committal face. There glowed no ray of hope for me behind those bright

brown eyes and the carefully trimmed black beard. My heart slumped down into my

boots.

I much question if be then realized how great was the chasm of my ignorance.

If be did grasp this, he was gentleman and sportsman enough to conceal the fact.

I owe Besant Singh much for steering me safely through those trying days of my

noviciate.

The splendid Sikh had served with the Railway Police from the

very beginning of construction work on the railway, and for the past two years

had been in full charge of Nairobi's police station. He was a great 'shikari',

a brave man and worthy of the highest traditions of the gallant Sikh units in

the Indian Army in which he served with honour before transferring to the Indian

Police and then coming to British East Africa. Besant Singh had killed twenty-four

lions during the advance of the railway to Nairobi, making a habit of hunting

them with a .303-rifle, for which he possessed only .256 calibre ammunition. To

make these cartridges fit his rifle, he wrapped them around with paper. This intrepid

Sikh sportsman was a first-class shot, but there are not many who would have dared

tackle lions with ammunition that did not fit the rifle. Certainly I would not.

.

What, at first, seemed like almost insurmountable handicaps now faded into

comparative insignificance. Inspector Besant Singh was a tower of strength, often

saving me from making an abject idiot of myself through over-hasty action or sheer

ignorance.

From interviews with Trilok Singh Nayer, Nairobi

I have been very unfortunate in my life. Why? Because I was not able to

help my father. I was just too young to realise what was happening, or to be of

any use. This is what happened.

I have no idea what precisely prompted my

father - his name was Gurdit Singh Nayer -

to leave home in Lahore. Again, I was too young, too young to even think of asking

things like that. I just know that like other Indians seeking to improve their

economic prospects, he ventured into Africa to explore business opportunities

to see whether he could make a home in this part of the world. He left in 1889.

He wasn't an adventurous youth, he was a grown man of thirty-two, working for

the Bank of India.

Ultimately he reached Nairobi. He saw the business prospects were thriving, so he left the Bank and returned to Lahore to recruit artisans such as carpenters, blacksmiths, and masons. He arrived back in Nairobi with about fifty people and his personal capital. People like Labh Singh Sagoo, Bulaka Siugh, Bhawal Mal, Bhawani Shankar and Nauhria Ram Maini who later became key figures in the Indian community, were in the same gang. Shankar became the first president of the Hindu Punjabis' SSD (Shree Sanatan Dharam), Maini the second -

My father established his own furniture business in Nairobi, and did very

well. He made good quality furniture and was the first person in Kenya to import

teakwood from Burma. He did so well that by 1913 he had enough money to build

one of the most prestigious buildings in Nairobi, the 'Nayer Building'. It was

close to the old Uganda Railway line and during the First World War the Government

wanted to use the building as a warehouse so he leased it to them free of charge

or remuneration, Today, the former Nayer Buliding, now known as Kipande House

and occupied by the Kenya Commercial Bank, is considered as one of the 'Historic'

buildings in Kenya. And of course he owned other notable properties in town.

Before leaving India, my father got married to the only child of a high-up, wealthy

Lahori family. After he got settled in Kenya, he brought his wife, Damyanti, over

and all of us children were born here. (I was born in 1919, number six of eleven)

When I was very young we lived for a couple of years in Mombasa. I remember only

that we stayed in the Liwali's building. Mainly we lived in Nairobi, where the

Odeon cinema is now.

My father was a cultured person, versed in the Persian

language, and he gained respect as a musician, actor and dramatist. He was a very

generous person, and everything he could do to help other people. Helping people

how? Well, for instance he would contribute money for marriages when people couldn't

afford the expense.

He became a leading member in the Sikh community, and

was known by the title of Sardar. For many years he was a member of the main Sikh

temple in Nairobi, he Siri Guru Singh Sabha, but he had some dispute - politics,

not religion - with the management. He walked out. For half or year of so one

of the rooms in his Nayer Building was used as a Sikh Temple while he built

a proper one in the bazaar. It was opened in 1918.

To avoid having any sectarian

name attached to it, he called it simply the (Gurdwara Bazaar

- the essence of Sikhism is that it is for everyone, not just for one particular

group. Having built the Gurdwara, he handed over the keys for other people to

run it.

He was also a prominent person amongst the Indian Community at large. People like Allidina Visram (of Mombasa who had a school named after him), Suleman Virjee (later he had the Suleman Virjee Indian Gymkhana named after him), they were my father's friends - I saw them in our house. At one point he was chosen by the Indian National Congress here to represent the Indian Community to the Governor of those days.

And then - he had a disaster in his business. He lost all his wealth. How he lost it I can't say. I was too young to understand what was going on, so I never thought to ask him. I Just know that he became very worried. What I regret is that I was so young that I didn't realise what was going on, and that I wasn't old enough to help him. But even in those bad times - my mother told me - he would do what he could to help other people.

In 1932,

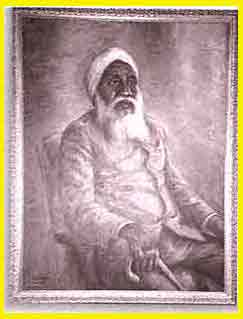

when I was only thirteen, he took us all back to Lahore. This photo of my father

was taken early that year, here in Kenya, shortly before we left. Soon after we

got to India he died. He was 75 years old.

My mother and all of us children

stayed there for five years. Then we returned to Kenya. Although my mother was

from a high up family and always dressed well with matching shoes and purse, she

was a down-to-earth-person. During the war she worked as a volunteer for St. Johns.

She died in 1984, more than half a century after her husband. She used to say

she had lived both like a queen and like a servant.

I know my mother did

what she could. It is only unfortunate that I could not help my father. I was

too young. I always tell young people to do what they can to help their fathers

because I was not able to myself I'm telling you, I have sad feelings about that.

THE

MECHANICAL MINDED GUNGA DIN

From Wheels Over Black Cotton By

]ohn Bate (pp 31-32)

The spare part situation in East Africa was always

generally good in my experience for the run of the mill vehicles. There were occasions

though, when the hole in wall garage or agent was a godsend. I remember one of

those types very well.

Lal Singh was

a motorcycle expert who plied his trade at the Victoria-end of Government Road.

During those early days he had been appointed an agent for one of the world's

most sought after piston rings. They still are!

I think Lal Singh was a little

upset at not being able to hoist the 'By appointment' sign outside his shed. Lal

looked like a wild Afghan tribesman during working and only needed a long rifle

to complete the illusion. A visit there invariably him squatting on his haunches,

gazing with Asiatic reverence, or bloody-minded at the entrails of a motor cycle

bleeding to death on the floor, depending on the and whether he had traced the

trouble.

Over the years, many a set of rings and other knick-knacks were bought

by me from old Lal Singh to be able to complete the engines of the weird (so I

was told) motors I couldn't resist acquiring.

A visit was always illuminating

and amusing. There was just enough room in the shed for one machine, provided

it had no sidecar.

The surrounding walls and rafters were a wonderful sight.

Old frames and wheels hung in garlanded profusion. Engines and gearboxes lurked

in dark corners. Tyres, tubes, etc. draped the rafters keeping company with the

varied chains and exhausts.

However, pride of place was reserved for a Welsh

dresser affair, modified over the years, and housing the new stock proudly for

all to see. Valves, pistons, chains, the odd exhaust pipe, carburettors, and boxes

of his pride and joy.

After the usual polite greetings were exchanged he would

say, "What you wanting sahib?"

"A set of rings for an Austin

7, (for example) ten-thou oversize," I would reply.

Lal would rise from

the floor and twist his trousers tip over a considerable paunch and pause to ponder

awhile. His ruminations were somewhat pedantic at times. He would stand with one

hand scratching his head, resulting in a sideways movement of his turban, sort

of rocking the boat exercise, and at others, a circular motion taking the turban

round in slow circles, whilst the other hand would be reflectively scratching

his -~ well, abdomen, I suppose, or thereabouts. It always reminded me of that

child's game we played donkey's years ago, rubbing the top of the head with one

hand and patting the stomach with the other without g

There would be much

muttering and a very downhearted, "Austin, oh my Gard," now and then,

the expletives usually spelling doom, out of stock. But no, he would open the

dresser affair and peering through the gloom, extract a cardboard box as though

it contained the Ten Commandments or Magna Carta and peer at the printed label.

Then a large smile would split that nuggety countenance revealing a couple of

gold teeth, and the correct parts would he handed to me. This mechanically minded

Gunga Din never failed once, with me anyway, to produce the part asked for. He

actually supplied me with a set of rings for my six cylinder Star. I thought that

I had him well and truly stumped here!

Why "Kalasingha" ?

There is a factual background as to why the whole of the Sikh Community is referred to by this unusual appellation of 'Kalasingha' mostly by the Africans. A sturdy, tough an an adventurous Sikh from the State of Patiala migrated to Kenya in 1896 at the age of 16. His name was Kala Singh. He started a progressive business under the name of Munshiram & Co. and became engaged in a very wide -spread business activities. He travelled through forests, barren lands and mountains, all in the times when there were no means of travel in any form. His exclusive adventures brought him in touch with the indigenous tribal people. S. Kala Singh particularly opened up the Masai reserve and made it accessible for people other than the Masai. This assisted in progress in trade and easy contacts for better understanding for the different peoples of Kenya. The traits and qualities of S. Kala Singh are still persistent in the Sikhs in East Africa so they are referred to as "KALASINGHAS"

Contributed by Hansraj Aggarwal, Nairobi

-A long time ago, it must have been in the 1880s or somewhere then, my grandfather Munshi Ram and his friend Kala Singh came to Kenya. They were both from the same village. Maur Mandi in Patiala State in the Punjab. Munsbi Ram's family was well to do, a family of Aggarwals, a Hindu business community in the Punjab. Kala Singh's peop1e were Jat Sikh farmers. In India Aggarwals were sort of commission agents. People like my great-grandfather Hiramal would buy produce, mainly grain from the farmers and then sell it. There was a big market at Maur (Mandi means market), and the businessmen and the farmers would meet there.

Munshi Ram and Kala Singh got to be friends in India and came over together. You know in those days there was no difference between Hindus and Sikhs. We were all called Hindus even the Sikhs. It was only when the Muslims began attacking the Hindus that some became warriors under the guidance of Guru Nanak Devji (Guru Gobind Singh Ji [Kanwal]). In my grandfather's time even now in India it wasn't only the Sikhs who wore turbans; all the older men wore turbans.

Kala Singh made an indelible mark on the minds of the Africans. He was a pioneer among Sikhs. He was a brave man and he travelled a lot away from the Railway line, in far off places in Masailand where his turban and beard were strange. Later Kala Singh and Munshi Ram brought many Sikhs from our village and most of them settled in Kijabe and in Loliando in Masailand. The most successful of the Sikhs who settled in Kijabe was Kehar Singh Dhillon, and he also had a shop at Loliando.(See part 2 -"Out of Africa")

About the same

time, perhaps even earlier, my grandfather's elder brother Anant Ram came to Kenya.

He also opened a shop on River Road. His son Darbari Lal also came here, and Grandfather

Palimal as well. I always called him grandfather but he must have been a cousin

of my grandfather's. He didn't stay long but later his son Kasturi Lal came and

opened up a business in Nanyuki. We were a prosperous family, working all together.

But we could have become much more prosperous. There was one Governor of Kenya

- I don't remember his name who used to go around to the Asian shops. He knew

my Grandfather well. He said to him, 'Mr. Munshi Ram, I'll give you some land,

about 10 acres, at a very cheap price (I think it was something like 10 shillings

or 50 shillings an acre). If you buy that land your children and your grandchildren

will remember you always because Nairobi is going to develop and it will become

extremely valuable property.' But my father replied we are only here for a few

years, for business purposes. We don't intend to settle we're well off at home.'

So he didn't buy that land. You know where it was?

The middle of it was

in what became the centre of Nairobi, where the statue of Lord Delamere used to

be (near New Stanley Hotel).

Ironically', my grandfather's family did

settle here. He never brought his wife over, but all his sons came. The wives

never came over in those early days. That was the general system of Indians. We

Aggarwals married other Aggarwals but the men here would get their wives in India

and leave them there, to raise the children. Munshi Ram got married to an Aggarwal

girl and they had three sons: W'aliati Ram, Puranchand and Lekraj who was my father.

All three came to Kenya but Waliati Ram only came to look, for being the eldest

he was running the family business back in India. Puranchand lived here until

1954 and then he returned to India with all of his sons.

When my father grew

up he was married in India to a girl named Durgadevi. But by then things were

different and ladies were coming to Kenya. She came and stayed here and had eight

children five sons and three daughters. We Aggarwals, the family of Munshi Rain

did a lot to develop Eldoret and Nanyuki and Timau but it is Kala Singh's name

who is most remembered by the Africans.

Kala Singh parted company with

my grandfather that's when our business name became Munshiram & Co.; and eventually

he went back to India and he died there.

No, it's not true that he had a Masai

wife. He was not that sort: he came from a good family' and had a wife back home

in India. He had one son who returned and lived in Arusha but I think now he too

has left. But Kala Singh is probably the best known name

in all of Kenya. To this day all Sikhs in Kenya are known as Kalasingas.

COPS

AND LIONS

From interviews with Mohinder Singh Chadha, Nairohi

My

family was helping maintain law and order in Kenya from the very beginning of

the century, for it was in 1901 that my eldest uncle, Ladha Singh Chadha, came

here. He had been in the police in India, in the town of Jhelum. Recruiting was

going on there for people to come to Kenya, and extra pay was being offered. So

Ladha Singh volunteered and came here.

He was first posted to Nairobi. He

used to make extra money by shooting lions, for the Government was offering 50

rupees per lion killed. He used to go to the river below where the museum is now

in the evening and wait for them when they came to drink. (I've never shot a lion;

there weren't any around Kericho where I grew up, and anyway I don't like killing.)

Subsequently he was transferred to many places, ending up in Nakuru, his post

when he retired. He came with his wife and infant daughter, and all the rest of

his children were born here.

The middle brother, Lakha Singh, was so very

well educated but his elder brother called him over anyway and got him a job with

the Prisons Department as a warden. He was stationed in Nairobi and several other

places, then finally at Kisumu.

The youngest brother was my father Bishen

Singh. Ladha Siugh called him over as soon as he finished his studies in 1907.

He was posted in Lumbwa (or perhaps it was Londiani), and then in Nairobi where

he was in the Intelligence section until he retired.

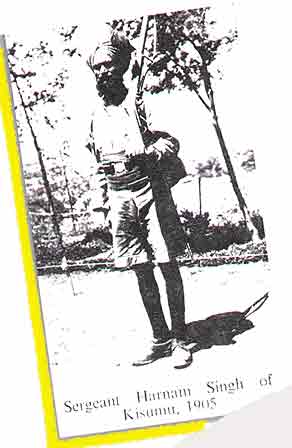

WITH A LEOPARD PERCHED ON HIS SHOULDERS

From Kill or Be Killed by W Robert Foran (pp 53-55 passim)

The hunt was

organised by G. McL. Tew, the Superintendent of the Railway Police; and he told

me the story of what happened. Three other Europeans and a stalwart Sikh policeman

volunteered to accompany Tew, and one afternoon they set out on their little private

war with the leopards. Between Nakuru and the lake is a wide grassy plain, covered

by scattered and stunted bushes . . .

The sportsmen passed through the long

grass in extended formation, shouting at the tops of their voices in the hope

of disturbing a slumbering leopard and getting a shot at it. Harnam Singh, the

Sikh policeman, easily drowned the noise of the others by his lusty shouts. Tew

said that he had every appearance of thoroughly enjoying his share in the hunt.

Finally, he noticed that the Sikh was lagging behind the line of attack, but paid

little attention to this, being far too intent on keeping his eyes watchful for

any movement in the grass to indicate a leopard's presence.

After a time, Tew became conscious that the Sikh was yelling louder than ever;

and now there was a note of extreme terror in his vocal efforts. He turned round

to see what was the matter. The Sikh was running toward them at top speed, with

his turban dragged off his head, and a big leopard perched on his shoulders. The

brute's body clung round the back of the man's neck like a woman's fur, and its

paws clutched at Harnam Singh's khaki uniform.

The others all ran back swiftly

to the man's assistance, while the Sikh rushed to meet them, yelling wildly. He

came bounding along with huge leaps, shouting in abject terror as he came. The

leopard was having a rough ride on his shoulders. No one dared to shoot, for fear

of hitting the Sikh instead of the leopard.

On seeing the other four men,

the beast appeared to take a sudden dislike to so much human company. It slipped

off its perch, flinging Harnam Singh to the ground in doing so, and slunk off

out of sight into the tall grass. Everyone was so much concerned with the Sikh's

plight that not a single shot was fired at the leopard. The injured man was hurried

back to Nakuru, where his slight injuries were treated and dressed. They were

mostly claw scratches, for the beast had not used its teeth at all.

Thereafter

nothing could induce Harnam Singh to go out on a hunting expedition! He served

under me for two years at Kisumu after this incident, but I had only to mention

the word leopard to see his big body shudder violently and his face go ashen-grey.

A

MODEL POLICE SERGEANT

From A Cuckoo in Kenya by W R. Foran (pp

102-106 passim,142~ 175)

At last, however, I held the key to the solution

of the burglaries in the [Kisumu] bazaar. As the Indian police alone patrolled

the bazaar region, I suspected something must be radically wrong with their work.

Without any warning, I moved them to the railway area and substituted African

askaris in the Indian bazaar. As if by magic, the burglaries there ceased immediately.

The natural inference to draw was that the Indian police were themselves the burglars.

I caused enquiries to be made as to the antecedents of these men and, in due course,

received a full report from Nairobi. For the most part they were men with bad

criminal records in India; while some were even wanted for crimes by the Indian

police. They had been engaged for police work in East Africa without any enquiry

as to their suitability. On landing at Mombasa, the entire twenty-five new policemen

were sent direct to Kisumu. . . . Only one, a Sikh, enjoyed a perfectly clean

record. . .

I retained the services of the Sikh, Harnam Singh. He had been

a 'naik' (corporal)

in the 14th Sikhs, serving with them through the Boxer

Rebellion in China, and then going on pension. Harnam Singh swore that he had

no knowledge of what was going on, and had not been in the confidence of the others.

I promoted him to sergeant and placed him in charge of the Indian bazaar area.

Harnam Singh proved a model police sergeant, and continued to serve well and honourably

until taking his discharge some years after I left East Africa. He was a fine

figure of a man, and upheld the best traditions of the Indian Army throughout

his career in Africa.

CATTLEMEN

From interviews with Mohinder Singh Chadha, Nairobi

When my father, Bishen Singli

Chadha, retired from the Police, he didn't want to go hack to India. He worked

for the Railway for a year or so, I think as an ASM (Assistant Station Master)

or perhaps as a Goods Clerk. In the meantime a European suggested to him that

he and his brothers {see 'Cops & Lions"] settle in Kenya. My father checked

around and decided that Kericho would be best for business and so in 1916 all

three brothers settled there.

Kericho is in Kipsigis country, and the Kipsigis

raised very good cattle, so Kericho had become a cattle-trading centre. There

were some Punjabi Muslims settled there, in the cattle business, and that is what

the brothers did too. They would buy cattle from the Kipsigis and then sell them

to the Somali traders who would then walk them to Nairobi and even Mombasa and

resell them. The brothers kept horses and mules and used to ride around to the

local markets, in the radius of about '30 miles, and buy cattle from the Kipsigis.

(When we children were little my father kept a brown pony for us; we all knew

how to ride in those days.)

The Kipsigis women liked heads and wire for ornaments

and it was cheaper to barter with such things than to pay cash for the cattle.

The brothers then started a shop, selling beads and wire, and sugar and such things.

'There were already some shops in Kericho one was belonging to the Anandji family

also were Gujaratis (i.e. Hindus; see To C.I. Sheet Shops in Kericho"]. The

brothers lived in a house behind the shop, all made of corrugated iron sheets.

In time the land around got taken up for planting tea and there were government

restrictions on the Kipsigis living around so the cattle became very few. The

Somalis began leaving Kericho. But my father and uncles stayed, starting a grocery

shop called 'B.S. Chadha and Bros'. They also built a grinding mill down by the

river, powered by the fast-flowing water. This was called a rego-rego' because

of the noise it made. Lakha lived down at the mill. My father stayed in the town

and looked after the grocery shop. Ladha and all his family went back to Jhelum

around then, in 1920, and he started a money-lending business -- we're still in

touch with our cousins on that side, Lakha never married. He kept a Nandi woman

as a wife for a year or so but they didn't have any children.

KERICHO

KIDS

My father got married when he was 25 and had been in

Kenya for several years.

He went back to India where his parents had arranged

for him to marry a girl named

Thakardevi. When my father returned to Kenya

she came too, for in those days

women followed their husbands like lambs.

I was their first child, born in Kericho 1918, on Christmas Day. The first World

War had just ended, in November, there were great celebrations in Kericho with

a big Victory Parade and trees e planted in the Boma to commemorate the occasion;

those trees and I are the same age.

After me another son was born, and then

two daughters; later there were more sons and two more daughters: we were ten

in all. Although money was scarcce we were happy in those days.

There were

only four or five Indian children in Kericho when I was little, not enough for

there to be a proper school. One shopkeeper hired a small maize store as a school.

It was cleared out so the sacks of maize were all piled up on one side and we

students sat on the floor on empty gunny bags. Our teacher was one local Gujaratis,

and I went there for my first two years of schooling. We only studied in Gujarati

(though my family is Punjabi speaking, of course). Later the Government primary

school, called the Kericho Highland Indian School, which went up to standard 6,

where English was taught. I also used to speak Kipsigis, the language of the local

people.

In 1926 my mother took all of us children (I had two brothers and

two sisters it) to India. It was the first time she had seen her parents since

she married here. We stayed two years in Daryajalib near jhelum, and then returned

in January1928. When we returned, my father sent me and my 'younger brother to

schooling, and my two sisters too. My mother came to look after us.

We went

to the Indian Primary School, which was about 200 yards from the KhalsaBoys and

Girls School. This school was made of corrugated iron sheets and it had only kindergarten

and Standard I. In that school we were taught in Urdu and we learnt oral English.

For Standards 2, 3 and 4 there was another school, opposite the Railway headquarters

are now. For the 5th Standard there was the Government Secondary School (now called

Jamhuri School). That had a hostel attached behind the school, so we lived there

and our mother was able to go back to Kericho. The girls went to the Punjabi Girls

School. One of my schoolmates was the son of Mrs. Mascrenhas, a Goan lady who

ran a shop in Kisii. She was a slim woman, very quiet. That is why she could compete

with the Gujaratis.

We used to go back to Kericho for vacations every three

months. The nearest train station was Lumbwa (it is now called Kipkelion); between

Lumbwa and Kericho we travelled by cart. My father had a small Scotch cart, the

kind covered with A tarpaulin, drawn by 7 pairs of oxen. We would leave Kericho

at 7 in the morning and do about 11 miles. Then we would stop and unyoke the oxen

so they could drink water and eat grass. We would spend the night in the jungle,

sleeping in the cart, while the drivers slept underneath. Then we would leave

early next morning and reach Lumbwa in time to each lunch at the dak bungalow.

The train would come in about 1 pm and stop for an hour so all the passengers

could eat at the dak bungalow too. There were waiters employed there, and the

food was very good. There were many different stationmasters and I can't remember

their names, except I recall that in 1938 there was one called Gurbachan Singh.

The train would travel all night and we would arrive in Nairobi about 9 in the

morning, and then we would hire a rickshaw, drawn by two men, to go to our hostel

- the rickshaw journey cost just 4 shillings.

CROSSING

KENYA WITH THE RAILWAY

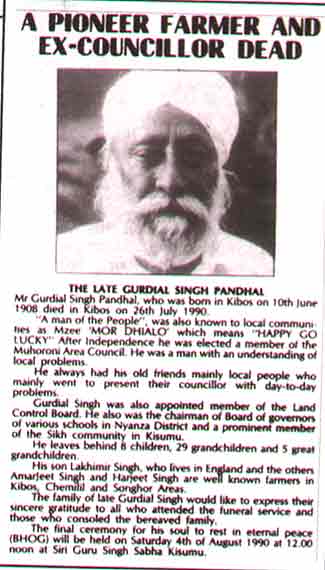

Contributed by late Gurdial Singh Pandhal.

Kibos

Oh yes, we've heen here a long time, a very long time. My father

got to Mombasa in 1894, before the Railway. He had a shamba there, everything.

My father Baba Jagat 'Macho Dogo' and a friend of his Lal Singh left India in

1892/3. They were from Jullunder District. They were very young and very poor.

They had no clothes, no money. They paid their passage on a steamer by firing

the boiler. They got to Mombasa even before the Railwav started. But when it started

my father got a job as a clerk, second division service. He was getting clothes,

food, accommodation and medical attention, plus 17 rupees 50 pice per month.

They worked their way up with the Railway. They left Mombasa and went to Changamwe,

the Railway headquarters. Then they moved with the Railway on to Mile 7. And so

they worked their way up the line. There were many Sikhs working on the Railway,

and Punjabis and Muslims. They got to Mackinnon Road. They and the Railwav continued.

People were being eaten by lions at Tsavo. They, the Indians, made a cave with

boulders to sleep in. But even so they weren't safe. My father saw one Indian

being taken by a lion. The Railway went on across the Rift Valley. Then near Fort

Ternan the Africans, the Nandi, stopped the Railwav for a while.

In 1901 the

Railway arrived at Lake Victoria and so did my father and his friend. The Railway

brought the steamer. My father stayed here a little while, near German Point.

There was sand there, lots of it, but there was no use for the sand; it was lake

sand and dirty. Then my father went to Port Bell.

People continued to settle

in this area, slowly, slowly. In 1914 came the war. Many people died. The British

and the Germans were competing to build a railway into Uganda. The British got

there first.

After the Railwav reached Kisumu, the Government

gave the employees tents and asked them to take up farming. Because the Indians

had worked very hard the

Government gave them 1500 acres divided between 30

people. Some people took

10 acres, some 50 and some 100, depending on what

they thought they could manage.

The land was between Kisumn and Muhoroni,

and the people were a mixed lot,

Gujaratis, Punjabi Muslims, Hindu Punjabis

and Sikhs.

My father was one of the people who got a farm. He got a farm No.

L. R.650/ 4,

105 acres of freehold land near the Kibos River. That was good

because he came of a farming family and knew about the work. He was a small man

but stout and very tough. The Government gave the land for farming but not any

implements, only some pangas.

It was all forest, you couldn't see your neighbours. The settlers cleared

the trees from the land with just pangas. My father and the others had to make

their own implements out of wood, there wasn't even iron for hoes or ploughs.

They'd do the final shaping using sharp stones.

When he was settled he called

my mother Raj Kaur. She came in 1906. I was their first child, born here on the

night of 10 June 1908. Then there was another son and four daughters.

The

Government liked the work my father was doing and they said to him to bring more

farmers like him from India. So my father went back to India in 1908/ 9 and brought

over family members such as his brother and others who wanted to come. They had

better tools but they still had a hard time. There were no roads. The nearest

railway station was at Kibos, two and a half miles from our farm. Other farms

were much farther away from the station, seven or eight miles. People used to

travel in ox-carts with roofs. The carts were made by carpenters from India, some

Sikhs and some others. Some carts had two wheels, others had four. People would

travel right up to Busia and Uganda in those ox-carts. People who didn't have

carts went on foot. It would take two to three hours to walk to Kisumu from our

farm. We didn't have donkeys in those days, although now we have some to pull

the weeding plows. We bought one horse but it died- its legs swelled up.

The

area was very unhealthy when we settled here, with many diseases. There was a