We

present with thanks an essay written by W.H.Mcleod in his book -'Exploring Sikhism'

AHLUWALIAS & RAMGARHIAS;TWO SIKH CASTES

The eighteenth century was a period of considerable turbulence for the Punjab. It began with Mughal authority still to all appearances in full control of the area, and it terminated on the threshold of a return to firm rule under Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Between these two periods, however, there were rebellions, invasions, a fragmenting of authority, political confusion. By the middle of the century, following the final collapse of effective Mughal power, there were emerging the celebrated Sikhs misls autonomous armed bands each under an acknowledged chieftain (sardar or misldar) and each asserting control over an ill-defined portion of central Punjab. During the period of their emergence a sense of unity was sustained, partly by the ties of a common allegiance to the Sikh faith but more effectively by the recurrent attacks of the Afghan invader, Ahmad Shah Abdali. Together with the preceding period of Mughal persecution these years constitute an interval of critical importance in the development of the Khalsa1 and exploits associated with it have secured an enduring popularity in Sikh tradition.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh

The removal of the Afghan threat in 1769 the precarious unity of the invasion years rapidly collapsed and for the remainder of the century political affairs in the Punjab were distinguished by inter-misl rivalry, leading on occasion to open war. Eventually one of Misaldars, Ranjit Singh of the Shukerchakia misl, by means of marital alliance, intimidation, and judicious use of force succeeded in eliminating almost all his rivals. The only major exception was the Phulkian misl which, because its territories lay in the Malwa region (south of the Satluj river), came within the ambit of the advancing British before Ranjit Singh could swallow it, and survived in consequence as a cluster of princely states. North of the Satluj Fateh Singh of Kapurthala managed to retain an empty title by accepting a thoroughly one-sided 'alliance' with Ranjit Singh. The fact that he succeeded in retaining his title was, however, important. We shall have reason to refer to the House of Kapurthala later in this essay.

Sikh misaldars holding a conference

Ranjit Singh belonged to a third generation of misl leadership. The first successful generation was the second (that of his father) and amongst the sardars of this middle generation his father does not stand out as one of the most prominent. Two sardars enjoy a particular prominence within this second generation, both of them bearing the name Jassa Singh. The older of the two first appears as Jassa Singh Kalal but subsequently Kalal was dropped and replaced by Ahluwalia. Similarly, his namesake abandoned his original name Jassa Singh Thoka in favour of Jassa Singh Ramgarhia. In accordance with these changes the groups which they led came to be known as the Ahluwalia and Ramgarhia misls respectively.

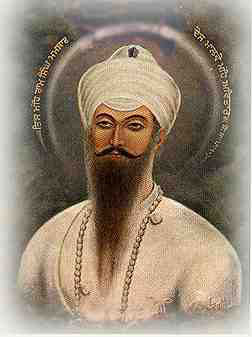

S.Jassa Singh Kalal (Ahluwalia)

For the purposes of

this essay both sets of names are important. In each case the change of name serves

to represent the process which the essay discusses, and all four are names which

must recur frequently during the course of the discussion. The original names

Kalal and Thoka designate castes, both of them artisan and both low in the status

hierarchy of the Punjab. The Kalals as brewers and distillers occupied a conspicuously

low ranking. Thoka means 'carpenter' and indicates a member of the a Tarkhan caste.2

The Tarkhan, or carpenter, caste ranked distinctively higher than that of the

Kalals or indeed of any other Punjabi artisan caste, but artisan it remained and

its actual status was in consequence comparatively low. Both ranked well below

the Jats, who were the dominant caste within the Khalsa and who were, during the

eighteenth century, establishing a much wider dominance over rural Punjab.

There

seems little doubt that the obvious explanation for this abandoning of caste names

must be the correct one. Both leaders sought to relinquish inherited names redolent

of lowly status. This they did by appropriating names more in accord with the

exalted status earned in each case by successful military enterprise. Jassa Singh

Kalal followed the common practice of assuming the name

of his native village.

This was a small place near Lahore named Ahlu or Ahluval and he accordingly came

to be known as Jassa Singh of Ahluval (Jassa Singh Ahluvalia).3 Initially his

namesake followed the same convention and, as a resident of Ichogal village (also

near Lahore), was known as Jassa Singh Ichogalia as well as Jassa Singh Thoka.

In 1749, however, he played a critical role in relieving the besieged fort of

Ram Rauni outside Amritsar.

S. Jassa Singh Ichogilia (Ramgarhia)

The

fort was subsequently entrusted to his charge, rebuilt and renamed Ramgarh, and

it was as governor of the fort that he came to be known as Jassa Singh Ramgarhia.4

Although the old caste appellation Thoka continues to appear in many later references,

Ramgarhia is clearly regarded as a more elevated title and later heroic literature

almost invariably refers to him by this name.

An understanding of the careers

of the two Jassa Singhs is certainly relevant to what follows. Our concern, however,

is not with two distinguished individuals of the eighteenth century, but rather

with the caste groups to which they belonged-with the means whereby sections of

both groups have subsequently endeavoured to enhance their corporate status, and

the degree of success each has achieved. The scanty literature dealing with the

two groups will be consolidated and, where possible, supplemented.5 Particular

attention will be directed to their common Sikh allegiance; the extent to which

status ambitions have encouraged conversion to the Khalsa; and the degree to which

the Sikh affiliation has encouraged and facilitated the continued pursuit of these

ambitions.

From this declaration of intent it is obvious that the discussion

must concern the issue of upward caste mobility. Does this necessarily imply that

it must in consequence concern Srinivas's celebrated theory of 'Sanskritization'?

The answer must be that, although a general correspondence may be discerned, the

'Sanskritization' formulations relating to caste mobility are more likely to confuse

than to enlighten and that the term ought, in consequence, to be eliminated from

the discussion. We are dealing with a comparatively simple process of emulation,

one which in its essential rudiments was recognized and understood by the earliest

of the systematic British observers of Punjabi society. In his treatment of Punjab

castes in the 1881 census Ibbetson includes a section entitled 'Instances of the

mutability of caste'. In this and the following section he gives several examples

of castes which have moved up or down in status by means of adopting or abandoning

particular customs or occupations.6 Although Ibbetson produced nosophisticated

theory to cover the phenomenon there can be no doubt that he and his colleagues

were well acquainted with its more obvious features as they manifested themselves

in Punjabi society of the late nineteenth century.

The case against retaining

the terminology of the Sanskritization debate in this examination of the Ahluwalia

and Ramgarhia communities can be illustrated by reference to the patterns of behaviour

which have provided models for Punjabi Kalal and Tarkhan imitation. These can

scarcely be described as brahmanical. In several respects they are distinctly

anti-Brahman in sympathy and in actual practice. The overt model has been the

Khalsa discipline, a pattern which represents the teachings of Nanak and his successors

transformed and extensively supplemented by the culture of the dominant Jats.

Neither Nanak nor his Jat followers betray a particular affection for Brahmans.

Nanak frequently goes out of his way to denounce brahmanical pretensions and specifically

the notion that real worth or salvation must necessarily relate to degrees of

caste status. Although Jats still showed a residual respect for Brahmans during

the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries,7 it has since dwindled to vanishing

point as they secured an increasing dominance over rural Punjab. Because the principal

Kalal and Tarkhan attempts come within this latter period it would be surprising

to find in them a conscious imitation of brahmanical ideals, apart from such as

have been retained within the Sikh faith or continuing Jat practice. This applies

most strongly in the case of theTarkhans who, as rural artisans dependent on landlord

patronage, have been in particularly close association with Jats.

II

Before

proceeding to discuss the Kalal and Tarkhan castes it is perhaps wise to clarify

the meaning of the term 'caste' when used in a Punjabi context. Within the Punjab

caste consciousness has comparatively little to do with the concept of varna,

except for those at the upper and lower extremities of the classical hierarchy.

For the bulk of the population the status hierarchy which really counts is one

which takes slight account of the traditional fourfold varna distinction. It is

in the Punjab a hierarchy, which exalts the mercantile Khatri and agrarian Jat

while tending to depreciate the Brahman. For the Jat the classical hierarchy has

little relevance except perhaps to increase the condescension which nowadays he

characteristically bestows upon

Brahmans. It has had relevance for the Khatris

as a means of claiming Kshatriya status, but even here its importance has been

only marginal. Khatri status obviously owes much more to commercial, industrial

and administrative success than to a dubious etymological assertion.8 As far as

this essay is concerned the only relevance of the traditional varna theory derives

from intermittent Kalal claims to Khatri status. The link is an exceedingly tenuous

one, as the target has been the actual Khatri mode rather than the vague status

of the warrior Kshatriya.

In Punjabi usage the term most commonly encountered

is zdt, a cognate form and synonym ofjati. The word is, in practice, used very

loosely and one must frequently construe its meaning from the context. It may

refer to the larger endogamous unit of caste organization; to the smaller exogamous

unit, or to the groupings of exogamous units. In some contexts it may even be

used to signify varna.9 A strict definition is, however, possible and it designates

one of the two major units of caste organization in the Punjab. In its strict

sense zdt connotes the larger endogamous unit and is thus properly applied to

such groupings as Khatri and Jat. The smaller exogamous units, which together

constitute the zat or jati, are called got (Hindi gotra).

In Punjabi society

it is the adt hierarchy which is most significant and it is upon his zat s ranking

that an individual's status will normally depend. Within each zat, moreover, one

can expect to find an internal got hierarchy of varying clarity and precision.

Kalal and Tarkhan are both regarded as zats, each containing its own gots. This

much is clear and easily understood, and it retains its clarity as long as the

discussion is confined to the Kalals. In the case of the Tarkhans, however, an

interesting complication is introduced following the assumption of the tide Ramgarhia

by Sikh Tarkhans. Sikh members of other artisan zats, notably the Lohar (blacksmith)

and Raj (mason), have also claimed to be Ramgarhias and on the whole their claim

has been accepted by Punjabi society in general. This has, in effect, created

a new composite Ramgarhia zat by an alliance of the Sikh segments of various artisan

zats. It should be added that the alliance has been an unequal one in most areas.

In practice the Ramgarhia grouping has always been overwhelmingly dominated by

its Tarkhan constituency.

One other term, which will be encountered in any

detailed investigation of caste relationships, is baradari (lit. 'fraternity'),

the group responsible for making decisions which affect the members of any given

got. In theory the baradari embraces the entiremembership of the got. In practice,

however, baradaris are much more restricted in size than the theory would suggest.

The effective biradari is much more likely to comprise the members of a particular

got within a single village or group of contiguous villages. Each got will thus

have many baradaris and the number of baradaris in any given area will approximate

to the number of gots. These baradaris have been important in terms of caste mobility.

Movement in either direction has only partly been the product of fortuitous changes

in external circumstances. Positive decisions by baradaris (as for example in

such areas as education) have commonly produced significant local results, some

of which will have spread by imitation to got members in other geographical areas.

The action taken by many Sikh Tarkhans in returning themselves as Ramgarhias in

the 1921 and 1931 censuses presumably represents baradari decisions in most

instances.

III

Having

thus defined three of the key terms we can return to the Kalal and Tarkhan zats,

and specifically to the question of when they first entered the Sikh community

in substantial numbers. This is a very difficult question to answer satisfactorily,

as there exist neither statistics nor detailed reference for the entire period

preceding the 1881 census. The earliest British observers, writing in the late

eighteenth century, were plainly under the impression that the overwhelming majority

of Khalsa Sikhs were fats.10 The impression is understandable as all the evidence

(both from contemporaneous sources and from the censuses of a century later) confirm

a strong preponderance of Jats. It seems likely, however, that there may have

been some measure of exaggeration in their emphasis. Pre-Khalsa sources (notably

the eleventh var of Bhai Gurdas) point to a significant Khatri constituency, plus

a sprinkling from several other diverse castes. Although the Khatri proportion

failed to carry over in the same strength into the Jat-dominated Khalsa it is

clear that the Khalsa has always included an indeterminate minority of non-Jats

and that particular individuals from amongst this composite minority have achieved

high rank in its counsels. The two Jassa Singhs testify to this general truth

and to the specific presence of both Kalals and Tarkhans.

Beyond this observation

we are, however, reduced to little more than cautious; conjecture, much of its

based upon the appreciably later evidence of the censuses. In the case of the

Kalals we can assume that in terms of influence as well as numbers their pre-census

representation

was small. The same may also be posited with regard to the influence of the Tarkhans

but not with reference to their numbers. The Tarkhans were, after all, tied to

the Jats in an intimate jajmani relationship and if the patron chose to follow

a particular way it would scarcely be surprising if the client should do the same.

This might be unlikely in the case of a lowly menial, but not for the higher ranks

of the artisans. Scattered hints offer some small support for this assumption.

There are, for example, the reference in police files concerning Baba Ram Singh,

leader of the Kuka sect of Sikhs from 1862 until his deportation in 1872. Ram

Singh was himself a Tarkhan Sikh and in a police report of 1867 on the Kukas it

is claimed that 'converts are chiefly made from Juts, Tirkhans, Chumars, and Muzbees'.11

Baba

Ram Singh

Baba

Ram Singh

This is, however, essentially conjecture.

With the appearance of the 1881 census light begins to break. A total of 1,706,909

persons were returned as Sikhs at this census. As everyone had expected the caste

analysis of this figure produced a pronounced absolute majority in favour of the

Jats (more than 66 per cent of the total community). The second-largest figure,

however, produced a surprise. From the Jat total there is a spectacular drop to

the second-largest constituent which, it turns out, is provided by the Tarkhans

with 6.5 per cent.12 Other constituents in excess of 2 per cent were the two outcaste

groups of Chamar (5.6 per cent) and Chuhra (2.6), the Aroras (2.3), and the Khatris

(2.2 per cent). The Kalals with 0.5 per cent emerge as one of the smallest of

the remaining twenty zats appearing in the census table.13 Another table lends

some support to the theory that Tarkhan adherence to the Khalsa will have derived

its impulse from the jo/mam relationship with Jats. Abstract 55, 'Distribution

of Male Sikhs by Caste for Divisions', shows a parallel area concentration of

Jats and Tarkhans.14

Elsewhere in the 1881 Census analyses of religious affiliation

are provided for each caste. Out of a total of 40,149 Kalals 22,254 were returned

as Hindus (55.4 per cent), 8,931 as Sikhs (22.2 per cent), and 8,964 as Muslims

(22.3 per cent).15 Tarkhans totalled 596,941. Of these 219,591 were Hindus (36.8

per cent), 113,869 were Sikh (19 per cent), and 263,478 were Muslims (44.1 per

cent).16

A similar range of figures are provided in the 1891 Census, but thereafter

the Kalals are dropped from the tables which provide informative analyses. There

is, however, no reason to assume that the Kalal trend will have been significantly

different from that of the Tarkhans or of the Sikh returns as a whole. The Sikh

Kalals doregister a small proportionate drop during the decade 1881-91, but so

too does the overall Sikh total. Thereafter both the Sikh total and that of its

Tarkhan component register comparatively steep rises through to the 1931 Census

(the last to incorporate caste returns) and it is probably safe to assume that

the Kalal component also increased. The 1931 Census gives the following figures:17

figures

for Sikhs

1,706,909*

1,849,371*

2,102,813

2,881,495

3,107,296

4,071,624

Percentage

increase

8.4

13.7

37.0

7.8

31.0

822

809

863

1,211

1,238

1,429

1881

1891

1901

1911

1921

1931

The same Census also provides a table showing 'for each of the last six censuses the variations in the population figures of certain castes, which claim both Hindus and Sikhs among their members'. This table includes the following entry for Tarkhans:18

Hindu 213070

Khan

Ahmad Hassan Khan, author of the 1931 Census Report, explaining the apparent drop

in the number of Sikh Tarkhans following the 1911 Census, indicates that the earlier

pattern of increase had in fact continued through to 1931. He says:

Among occupational

castes, such as Tarkhan and Lohar, Hindus have been decreasing since 1901, while

the number of Sikhs has been rapidly growing, though of late it has had a downward

tendency. This is merely due to the failure on the part of Sikh artisans to return

any caste at all or to claim Ramgarhia as their caste instead of the traditional

caste, Tarkhan.19

Although one must certainly treat these census returns with

considerable caution it is obviously safe to conclude that the period from 1891

to 1931 is marked by a substantial movement within several castes away from a

Hindu identity to a conscious Sikhidentity. The Tarkhan zat is one such caste

and given the nature of the general trend it would be extremely surprising if

the Kalals were not another. Earlier in his report Khan explain the trend:

The

main conclusion is that the varying strength of the population returned as Hindu

or Sikh in the Punjab States is due to social causes that are at work in that

section of the population from which both Hindus and Sikhs are drawn. The Akali

movement during the last decade is mainly responsible for numerous persons being

returned as Sikhs instead of Hindus. Such persons for the most part comprise members

of depressed classes, agriculturists and artisans in rural areas, who obviously

consider that they gain in status as soon as they cease to be Hindus and become

Sikhs.20

This comment here restricted to the princely states is subsequently

extended to cover the bulk of British Punjab.

The main cause for the discarding

of Hinduism by some of the agricultural and artisan classes in the central and

eastern Punjab is the enhanced prestige gained by agricultural tribes in the countryside

by their becoming Sikh .... Similar influences are operative in the case of such

tribes as Tarkhan (carpenter), Lohar (blacksmith), Julaha (weaver), Sunar (goldsmith)

and Nai (barber).21

IV

Up to this point the Kalal and Tarkhan zdts have

been considered together. This has been convenient insofar as they manifest a

similar impulse and produce similar responses. There are, however, distinctive

differences and each will now be treated separately.

Ibbetson's classic Report

on the 1881 Census of the Punjab pro-vides the first systematic description of

the Kalal caste in general and Ahluwalias (Sikh Kalals) in particular. In this

brief account he refers to Jassa Singh's assumption of the name Ahluwalia and

indicates that the borrowing of the name by Sikh Kalals was already general by

1881. The caste', he adds, 'was thus raised in importance' and in consequence

'many of its members abandoned their hereditary occu-pation [as distillers].'22

Ibbetson here implies as consequence what was probably a simultaneous process,

directed towards the same ob-jective. Moreover, he refers in the same description

to an economic incentive for renouncing the traditional Kalal vocation. This was

pro-vided by British regulation of the distilling and sale of spirits. As a result

of the restrictions thus imposed many Kalals, particularly Sikhs and Muslims,

had 'taken to other pursuits, very often to commerce,

and especially to traffic

in boots and shoes, bread, vegetables, and other commodities in which men of good

caste object to deal'. He adds: They are notorious for enterprise, energy, and

obstinacy.'23

Ibbetson indicates that the Sikh Kalals (whom we must henceforth

call Ahluwalias24) were in a period of transition during the late nineteenth century.

Another British observer writing less than twenty years later accepts the fact

of change but disagrees with regard to its direction. In his Handbook on Sikhs

for Regimental Officers (Allahabad, 1896) R.W. Falcon claims that most Ahluwalias

had become agriculturalists.25 Falcon, however, writes from personal observation

rather than from statistics and the claim which he makes probably amounts to an

impression derived from experiences as a recruiting officer, an occupation which

directed attention to rural rather than urban groups. His statement should probably

be regarded as a supplement to Ibbetson's information. We thus retain the clear

impression of a caste in transition, moving in response to both economic pressure

and deliberate choice. By the end of the nineteenth century many Ahluwalias had

taken up agriculture and many more had moved into petty commerce. Some were already

securing positions of responsibility in the army or civil administration, and

others were appearing as lawyers.26

This process has continued throughout the

present century, with the result that although Ahluwalias may still be found in

petty commerce this is scarcely the image they project. Ahluwalias are now to

be found in more exalted commercial enterprise and particularly in government

service where many have achieved notable success. Some have achieved prominence

in the army. Others have done so in literature and the universities, earning for

themselves an acknowledged reputation as intellectuals. One of the finest flowers

of Punjabi literature was in fact of Ahluwalia origin, the result of a decision

by the Ahluwalia barddarl of the Abbotabad area to send two of its young men to

Japan for their education. One of these, Puran Singh (1881-1931), matured into

a poet of considerable renown within the Punjab.

Ahluwalias' status today is

unquestionably a high one in Punjab society and few would deny them an honourable

rank. It is, how-ever, by no means clear what specific status the Ahluwalias have

aimed to achieve, nor what precise status they are accorded in mod-ern Punjabi

society. The target of the Kapurthala princely family (the descendants of Jassa

Singh Ahluwalia) appears during the later nineteenth century to have been Rajput

status.27 For at least some

Ahluwalias there appear to have been Jat ambitions,

but if so these have been frustrated by Jat unwillingness to intermarry. As a

whole the community seems generally to have regarded Khatri status as the desired

objective, a claim which once produced a short-lived 'All India Ahluwalia Khatri

Mahasabha'.28 Solid evidence is not avail-able, but one will often encounter claims

that increasingly Ahluwalias are marrying Khatris. For a group moving strongly

towards urban residence and commercial or professional occupations the Khatri

identity provides an appropriate target.

The details are imprecise, but of

the general outcome there can be no doubt. A fair summary of current attitudes

was probably provided by a conversation with three Sikh graduate students (all

non-Ahluwalias) in 1972. When asked to identify the caste status of the Ahluwalias

one volunteered the suggestion that they must be Jats, a second linked them with

the Khatris, and the third did not know. None were aware of any links with the

Kalals. Ahluwalia success is, it seems, assured. It can be attributed partly to

the comparatively lengthy spread in temporal terms of their ascent to a respectable

corporate status; partly to the relative smallness of the community; partly to

its association with the princely house of Kapurthala; and partly to the intelligent

determination of so many individual Ahluwalias.

V

The experience of the

Ramgarhias has been distinctly different, notwithstanding the place of high honour

accorded individual Tarkhans in Sikh history and tradition. Jassa Singh Thoka

we have already noted. Even higher in the traditional estimation stands the figure

of Bhai Lalo, a carpenter who plays a central part in one of the most popular

of all janam-sakhi stories about Guru Nanak.29 As we have already seen, however,

their strength and status within the Sikh Panth remains generally obscure until

we reach the later nineteenth century.

Bhai Lalo, Bhai Mardana, Guru Nanak & Rai Bular Bhatti

Ibbetson's

brief description of the Tarkhan caste suggests that in 1881 there was little

evidence of the conscious mobility he notes in the case of the Ahluwalias.30 By

1891, however, the proportion returned as Sikhs was already rising31 and in 1896

Falcon noted that Sikh Tarkhans were commonly called Ramgarhias,32 a title earlier

used only by the direct descendants of Jassa Singh Thoka.33 In the 1901 census

4,253 Sikhs returned themselves as Ramgarhias. Aparticular concentration in Gurdaspur

district (1,548) indicates the connection with Jassa Singh's descendants, most

of whose estates were located in that area.34 The usage had, however, ceased to

be a family preserve and its incidence increased rapidly through the three succeeding

decennial censuses. Today, if a caste label is to be used for a Sikh of Tarkhan

origins, it will almost invariably be Ramgarhia.

This increasing popularity

of the name Ramgarhia during the present century accompanies a steady increase

in the economic status of many SikhTarkhans (for some a positively spectacular

increase). In 1896 Falcon warned his readers that a Tarkhan Sikh 'can rarely be

persuaded to enlist on a sepoy's pay as an average carpenter can make Rs. 20 a

month in his village'.35 This was but a small beginning for what was to follow.

From their homes in rural Punjab numerous Ramgarhias began to travel increasing

distances in response to a substantial British demand for their services. The

development of communications and industry required in large measure precisely

those skills, which the Ramgarhias were able to provide. Carpentry in Shimla,

railways in eastern India, contracting in Assam, and a combination of the same

opportunities in East Africa progressively attracted the services of the willing

Ramgarhia and brought him a mounting economic return. It need occasion no surprise

that the largest section of East African Sikhs is still that of the Ramgarhias.36

The

economic success achieved outside the Punjab has subsequently been repeated within

the Ramgarhias' home state, much of it on the basis of profits repatriated from

other pans of India and from East Africa. Two features distinguish this Punjab-based

enterprise. The first is its specialization in small-scale industries which relate

closely to the traditional Tarkhan vocation. Furniture-making and agricultural

machinery are two prominent exam-ples. The second distinctive features has been

a concentration in particular towns, notably Phagwara (auto parts and other industries),

Kartarpur (furniture), and Batala (foundries and agricultural machinery).37 Concentrations

also occur in Ludhiana and Goraya, and impressive fortunes have been made by Ramgarhia

contractors in New Delhi.

These enterprises convincingly demonstrate a substantial

economic achievement on the part of numerous Ramgarhias. Has their success in

the economic area been accompanied by a corporate social rise of any significance?

Although individual Ramgarhias of considerable wealth appear to be achieving a

measure of success in terms of mar-riage arrangements the corporate status of

the community still ap

pears to be essentially unchanged. This failure has

not been the result of complacence or inactivity. In addition to their Sikh affiliation

and change of name the Ramgarhias have, during the past half-century, achieved

a notable degree of corporate cohension and engaged in the kind of corporate activities

which are believed to foster advancement under twentieth-century conditions. These

include the formation of Ramgarhia sabhas (societies), the erection of Ramgarhia

gurduaras (temples), the publication of a Ramgarhia Gazette, and above all the

development of an impressive educational complex in Phagwara. This complex now

includes a degree college, a teachers' training college, a polytechnic, an industrial

training institute, and several schools.38 It is, moreover, evident that Sikhs

of other artisan castes have believed . the corporate status of the Ramgarhias

to be a desirable one, with the result that Lohars and Rajs have adopted the title

and been accepted into the predominantly Tarkhan community. These factors notwith-standing

it remains apparent that in terms of corporate status the Ramgarhia community

has achieved a comparatively slight success. Certainly it is appreciably less

than that of the Ahluwalias.

The future may, of course, produce change in corporate

status corresponding to economic success; or it may simply provide for a progressive

weakening of caste hierarchies, reducing the present corporate status to meaningless

relics. The present provides, in the case of the Ramgarhias, an unusually interesting

composite zdt grouping, built around a substantial core of Sikh Tarkhans but somewhat

indistinct at its edges. In addition to Lohar and Raj accessions some Nais (barbers)

and a few Gujars have also assumed the Ramgarhia mantle. Amongst its more prominent

gots are the Kalsi (named after a village in Amritsar District), the Mohinderu

(borrowed from the Khatris), and the Matharu. In spite of its impressive educational

apparatus in Phagwara the community has produced few scholars and little evident

willingness to use education (in the manner of the Ahluwalias) as a means of professional

advancement. Very few Ramgarhias will be found in administrative positions and

there seems little likelihood that this situation will change. There has, however,

been an interesting tradition in many Ramgarhia families of providing granthis

(or readers) for gurduaras. Another interesting specialization has been art. Much

of the marble inlay and many of the frescoes in the Golden Temple are the work

of Ramgarhia craftsmen.39

The current condition of the community in terms of

coherence and solidarity is difficult to estimate. Saberwal suggests after a periodof

research in 'Modelpur' (Phagwara) that the Ramgarhia coherence in that particular

area is now dissolving as baradaris, lose their authority and as Ramgarhias of

elevated individual status increasingly seek marriage arrangements outside the

community. Ramgarhia involvement in politics has, he maintains, been sparse in

the past and for the future it is at once unnecessary and impossible.40 A different

impression emerges, however, from the Batala area. Informants in Batala (one of

them a former member of the Punjab Legislative Assembly) claimed that locally

the Ramgarhias are well organized (at least politically). In recent elections

(Punjab state elections of March 1972) their support has been given to the Congress,

not to the Akalis whom they identify with Jat interests.

A report from yet

another area indicates a similar degree of local cohesion, but a different beneficiary.

Nayar found that the Ramgarhias of the rural Sidhwan Bet constituency in Ludhiana

District voted solidly Akali in the 1962 elections because 'they insistently wanted

to prove that they are as good Sikhs as any other, and the act of voting for the

Akali candidate becomes a form of self-assurance and a public demonstration of

being a complete Sikh'.41 The difference between Batala and Sidhwan Bet is perhaps

explained by a contrast between comparative Ramgarhia affluence in the former

and backwardness in the latter. Whereas the Ramgarhias of Sidhwan Bet were still

seeking to secure the status associated with their Sikh affiliation, those of

Batala are more concerned to maintain favour with the Congress party which, as

the central Government, can so affect the fortunes of small industries. In a general

sense it seems reasonable to conclude that whereas there is no uniformity of Ramgarhia

political policy at the provincial level there are, in at least a few areas, evidences

of effective local unity.

Amongst individual politicians two Ramgarhias have

achieved notable prominence in recent years. The former Chief Minister of the

Punjab, Giani Zail Singh was Ramgarhia and the first of the community to occupy

a position normally held by a Jat.

Giani Zail Singh the first Sikh President of India

He was later

President of India. The late Dalip Singh Saund, the first Indian member of the

United States Congress, was also a Ramgarhia.42 In each case the success should

probably be regarded as essentially personal.

VI

Ahluwalias and Ramgarhias,

both of them caste groups within the wider Sikh Panth, have thus had differing

success in their commonquest for higher status. We conclude with the questions

raised at the beginning of this essay and since then treated only indirectly.

To what extent has this quest for higher status encouraged conversion to the Sikh

Khalsa; and to what degree has conversion subsequently favoured its pursuit?

Although

the first question must defy a precise response, it can be easily answered in

a general sense. The census figures alone, testifying as they do to extensive

lower caste conversion over the course of at least half a century, demonstrate

the appeal of the Khalsa to those dissatisfied with their inherited status. The

Sikh Gurus had preached the religious equality of all castes and coinciding with

the period covered by the censuses the Singh Sabha reform movement stimulated

a significant recovery of this message. Within the Khalsa the customs of sangat

and pangat*3 are meaningful conventions and all who join it share in the measure

of equal status which they confer. The Khalsa was, moreover, an institution of

acknowledged prestige and influence. Within it caste distinctions may have survived,

but it offered a promise of equality which was by no means wholly belied. This

applied to the Ramgarhias as well as to the Ahluwalias. Tarkhans they may have

remained, but their status was plainly superior to that of their Hindu caste-fellows.

Apart from the reputation of the Khalsa there appears to be no explanation to

account for this difference.

This acknowledgement provides a part of the answer

to our second question. In purely economic terms we can, however, proceed further

with this question. Saberwal argues that the Sikh symbols, imposing as they do

an outward uniformity, enabled Ramgarhias who moved beyond the Punjab to escape

from the constricting status of menials.44 The recognizably Sikh exterior could,

in fact, achieve even more.

In the eyes of foreigners Sikhs belong to a single

community, and qualities attributed to the community as a whole have frequently

been ascribed pari passu to its individual members. This would mean that the Sikh

reputation for freedom, vigour and initiative (a reputation largely earned by

the lats) might well be extended to all who bore the external symbols.

There

is perhaps a degree of exaggeration involved in this as the instructions issued

to army recruitment officers betray if anything an excessive concern for character

differences allegedly based on caste distinctions amongst the Sikhs. At the same

time there also appears.] to be a measure of truth in it, a measure which probably

increased as one moved away from army circles. The same willingness to endowall

Sikhs with a common identity survives today in such instances as the reputation

accorded Sikh taxi drivers. To be visibly a Sikh commonly means receiving both

the benefits and disadvantages conferred by the composite Sikh reputation.

Others

have attempted to go still further in claiming particular qualities for the Sikh

regardless of his caste. The Khalsa rahit (code of discipline) is said to bestow

advantages in terms of a regular disciplined life; and the specific ban on tobacco

effectively debars the Sikh from a deleterious habit. Here, however, we broach

issues which are debatable to say the least. The rahit is unquestionably a powerful

means of personal discipline if in fact it is rigorously observed, but there is

little evidence to indicate a widespread contemporary rigour. Whereas it certainly

applies to many individual Sikhs, few would allow the claim to cover the Panth

as a whole. Although the ban on smoking is almost universally observed by Sikhs

some might want to suggest that gains made here are lost on liquor.

The most

one can claim is that the Sikh way of life offers a possibility of temporal success

and the certainty of enhanced personal respect for those individuals who strictly

observe its precepts. To castes as a whole it offers the same benefits, but to

an appreciably diminished degree. The varying success of the Ahluwalias and Ramgarhias

suggests that for substantial gains in status other means are also required.

Notes

1.

The Sikh order, with its distinctive symbols and discipline, instituted by Guru

Gobind Singh in 1699.

2. The Punjabi thoha and Hindi tarkhdn are synonymous.

The latter, however, is almost invariably used as the caste designation.

3.

Hari Ram Gupta, History of the Sikhs 1739-1768 (Simla: Minerva Book Shop, 2nd

rev. edn, 1952), 1, p. 50n.; Kanh Singh Nabha, Gurusabad Ratandkar Mahan Kosh

(Patiala: Bhasha Vibhag, 1960), p. 372.

4. Gupta, op. cit, pp. 61, 90-1; Kanh

Singh Nabha, op. cit., p. 372; Teja Singh and Ganda Singh, A Short History of

the Sikhs (Bombay: Orient Longmans, 1950), pp. 138-9, 141n.

5. The principal

sources are the successive Punjab censuses from 1881 to 1931. Ibbetson's important

Report on the 1881 census was subsequently reissued under the title Panjab Castes

(Lahore: Punjab Government, 1916). R.W, Falcon, Handbook on Sikhs for the use

of Regimental Officers (Allahabad: Pioneer Press, 1896) offers a conspectus of

Sikh castes, but adds little to Ibbetson with regard to Kalals and Tarkhans. The

only extended treatment of either caste provided by a modern authority is Satish

Saberwal's valuable contribution on the Ramgarhias, 'Status,

a

Mobility

and Networks in a Punjabi Industrial Town', Beyond the Village: Sociological Explorations,

ed. Satish Saberwal (Simla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study, 1972). More can

be expected from this author. Both groups are briefly and usefully described in

their nineteenth-century context by P. van den Dungen in D.A. Low (ed.), Soundings

in Modem South Asian History (Canberra: Australian National University Press,

1968), pp. 64-5, 70-1.

6. Census of India 1881, (Lahore: Her Majesty's Stationery

Office, 1883), I, Book I, 174-6, Also Ibbetson, op. cit., pp. 6-9.

7. Avtar

Singh, Ethics of the Sikhs (Patiala: Punjabi University, 1970), p. 161.

8.

The words ksatriya and hhatri are cognate terms, the latter Punjabi form apparently

assumed as yet another example of upward mobility by means of caste titles.

9.

Cf. Andre Beteille, Castes Old and New (Bombay: Asia Publishing House, 1969),

pp. 146-51.

10. Ganda Singh (ed.), Early European Accounts of the Sikhs (Calcutta:

Indian Studies Past and Present, 1962), pp. 13, 56, 105. The impression was still

abroad in the mid-nineteenth century. Cf. W.H. Sleeman, Rambles and Recollections

of an Indian Official. Rev. edn Annotated by Vincent A. Smith (Karachi: Oxford

University Press, 1973), p. 476n.

11. W.H. McLeod, The Kukas: a Millenarian

Sect of the Punjab', W.P. Morrell: A Tribute, eds G.A. Wood and P.S. O'Connor

(Dunedin: University of Otago Press, 1973), p. 86. See above, p. 190.

12. Ibbetson

comments: The [numerically] high place which theTarkhans or carpenters occupy

among the Sikhs ... . is very curious'. Census of India 1881, I, Book I, p. 108.

13.

Ibid., p. 107.

14. Ibid., p. 139.

15. Ibid., II, table VIIIA, p. 26.

16.

Ibid., p. 8. A small discrepancy between the totals for each religion and the

grand total appears in both Kalal andTarkhan figures because of returns made by

Jains and Buddhists.

17. Loc. cit., XVII, Part I, 304. To this table an important

qualification was added: 'Apart from the facts set forth in the extracts quoted

above, the number of Sikhs since 1911 has greatly risen on account of the changed

instructions about the definition of Sikhism. Prior to that year only those were

recorded as Sikhs, who according to the tenets of the tenth Guru, Gobind Singh,

grew long hair and abstained from smoking, but since then any one is recorded

as a Sikh who returns himself as such whether or not he practices those tenets.'

(Ibid., p. 306.) It is, however, a qualification which almost exclusively concerns

Khatris and Aroras. Neither the Ahluwalias nor the Ramgarhias have observed to

any significant degree the practice of calling themselves Sikhs without observing

the outward forms of the Khalsa. For them this would havedestroyed any social

advantage implicit in the title of Sikh. Indeed, the title would not have been

accepted as valid.

18. Ibid., p. 308.

19. Ibid., p. 309.

20. Ibid., p.

293.

21. Ibid., p. 294. On the specific case of the Tarkhans see also pp. 337,

346.

22. Ibbetson, op. cit., p. 325.

23. Ibid.

24. This is sometimes

abbreviated to Walia in modern usage.

25. Loc. cit., p. 78.

26. P. van den

Dungen, op. cit., p. 71.

27. Punjab District Gazetteers, XIVA ]ullundur District

and Kapunhala State 1904 (Lahore: Punjab State Government, 1908), Kapurthala section,

p. 3.

28. Dev Raj Chanana, 'Sanskritization, Westernization, and India's North-West',

The Economic Weekly (Bombay), 4 March 1961, p. 410.

29. W.H. McLeod, Guru Nanak

and the Sikh Religion (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968), p. 86.

30. Ibbetson,

op. cit., p. 313.

31. Census of India 1891 (Calcutta: Government of India,

1894), XIX, 335 and Appendix C, p. xcviii.

32. Falcon, op. cit., pp. 29, 77.

33.

It is used in this sense early in the nineteenth century by Murray in a document

posthumously published in 1834 as an appendix to H.T. Prinsep's Origin of the

Sikh Power in the Punjab. 'Intermarriage between the Jat Sikh Chiefs and the Aluwaliah

[sic] and Ramgarhia families do not obtain, the latter being Kalals and Thokas

(mace-bearers and carpenters) and deemed inferior.' Loc. cit. (1970 edition),

p. 164n.

34. Census of India 1901, XVII, Parti (Simla: Government of India,

1905), 137, 183.

35. Falcon, op. cit., p. 77.

36. Teja Singh Bhabra, The

African Sikhs', The Sikh Sansar (California), Vol. II, No. 3, 78. The economic

expansion is well described and acutely analysed by Satish Saberwal, 'Status,

Mobility, and Networks in a Punjabi Industrial Town', Beyond the Village, ed.,

idem.

37. Saberwal convincingly relates the Phagwara concentration to the development

of industry in the town with its consequent demand for skilled or semi-skilled

workers. Industry, he suggests, was attracted partly by road and rail connections;

and party by the town's pre-1947 location within a princely state (Kapurthala).

This latter feature meant freedom from British Indian tax scales. Ibid., pp. 128-30.

Kartarpur (Jullundur District) presumably owes its popularity, in part at least,

to the first and third of these factors; and Batala (a post-1947 development)

to its earlyRamgarhia conneaions. Situated within Gurdaspur District it has a

substantial Ramgarhia population.

38. Ibid., pp. 155-6.

39. 'Historical

Notes on the Ramgarhias: Record of Interviews with Sardar Gurdial Singh Rehill',

unpub. MS. prepared by Satish Saberwal. The popular Sikh artist Sobha Singh is

also a Ramgarhia: ibid.

40. Beyond the Village, pp. 157, 161.

41. Baldev

Raj Nayar, 'Religion and Caste in the Punjab: Sidhwan Bet constituency, Indian

Voting Behaviour: Studies of the 1962 General Elections, ed. M. Weiner and R.

Kothari (Calcutta, 1965), p. 138.

42. A brother of Dalip Singh Saund, Karnail

Singh, has achieved considerable personal eminence as a builder of railways in

Assam and subsequently as chairman of the Railways Board. Both positions, it will

be noted, are entirely congenial to Ramgarhia traditions.

43. Sangat: lit.

association, congregation. In Sikh congregations all must sit together regardless

of caste. Pangat: lit. a row of people sitting to eat. In the Sikh langar (the

communal kitchen attached to each gurdwara) no caste distinctions are permitted

with regard to seating. All dine together.

44. Satish Saberwal, 'On Entrepreneurship:

Everett Hagen and the Ramgarhias' (unpublished paper read at National Seminar

on Social Change, Bangalore, Nov. 1972), p. 10.