This article was written by Eric Cecil in 1973, which narrates the brief history of the East African Safari Rally. Although lots of action took place after 1973 - this introduction was deemed necessary . (Kanwal)

Introduction

Twenty-one

years after the first rally was run to mark the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth

II in 1953, the East African Safari Rally remains unique-an amalgam of gruelling

conditions and lOOkph average speeds through ideal, sparsely-populated country

unrivalled elsewhere in the world.

True, it now has its competitors. In Africa,

the Ethiopian Highland Rally and the Moroccan Rally duplicate some of the features

of the Safari; they may, indeed, siphon off a few of the would-be entrants from

the East African event. They can never match its unique character.

Motoring

News has called it "the most exacting test for man and machine yet devised

in the world of rallying." And world automobile manufacturers from Detroit

to Japan have been quick to note that success in the Safari is inevitably reflected

in a rise in the sales graphs of a market far wider than just East Africa.

How

did it all start ? Kenyans have long taken an interest in motor sport, and fifty

years ago the Royal East African Automobile Association had 1,000 members (83-2%

of all car owners in 1921). The Association-now the AA of East Africa and responsible

for the management of the Safari-had been founded in 1919 by L.D.Galton-Fenzi.

Galton-Fenzi

pioneered the Nairobi-Mombasa route driving a 1926 Riley. The trip took 15 days,

and from Voi to Mackinnon Road a track had to be hacked from the bush. He carried

out other surveys; Nairobi to Dodoma and on to what was Nyasaland and in 1931

across Africa to Lagos, through the Sahara to London.

In 1936, a road race

through the core of Africa from Nairobi to Johannesburg was staged, 2,715 miles

of route that had been largely pioneered by Galton-Fenzi. In a forward to the

route notes and maps for that race, he noted, "the marvellous strides made

in recent years as regards road construction and road maintenance." It was

a fortnight's drive from Cape Town to Nairobi.

The connection between those

early days and the present East African Safari Rally is tenuous, but real. In

1950 two Nairobi businessmen, Neil and Donald Vincent, had set a new record for

the Nairobi -Cape Town-Nairobi run. Later approached by their cousin Eric Cecil,

at that time chairman of the competitions committee of the REAAA, to race at Langa

Langa they were unenthusiastic.

The Langa Langa (present-day Gilgil) track

utilised the perimeter roads of a World War II military camp, providing a testing

3-3 mile circuit. Cecil was preoccupied with boosting interest in the track, but

the Vincents were non-committal. Instead, it is recorded, they made the alternative

suggestion that a long-distance drive such as they had undertaken the previous

year presented a greater challenge than going round and round a track.

So the

idea of the Safari was born. Cecil recalls that he thought initially in terms

of a road race around Lake Victoria, a proposition shelved when it was realised

that seasonal flooding in parts of northern Tanzania rendered this impracticable.

Eventually

various schemes and suggestions jelled. The Safari, to be run over roads in the

three East African states of Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, became a reality in 1953.

It was staged over the holidays that marked the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth

II.

Regulations were as brief and simple as possible. There were only eight

controls-compared to the 57 control points in the 18th Safari of 1970-and there

was no provision for rest en route. Classification of the strictly standard production

saloon cars was by showroom price rather than engine capacity.

In the stirrups - Martin & McIntyre jockey their Morris Mini Cooper S through a muddy patch near Dar-es-Salaam in the 1966 Safari

Right

from the start, the organisers had their paid members in mind and were out to

prove just what value the new car buyer was getting for his money. Not even strengthening

of the vital suspension that inevitably took a tremendous pounding on the East

African roads of two decades ago was allowed.

The changes in the intervening

years have been considerable. The team of four Ford Escort RS 1600s which won

the manufacturers' team award in the 1972 Safari were fitted with heavy-duty suspension,

long-range fuel tanks, full underbody protection against pos-sible severe damage

by rocks and competition brakes.

Each car was fitted with "roo bars"

in the event of possible collision with wild animals and the now compulsory roll

bars. The Ford service manager put the preparation cost of each car at £8,000

and a fleet of service vehicles and co-ordinating service plane may have added

£20,000 to the bill.

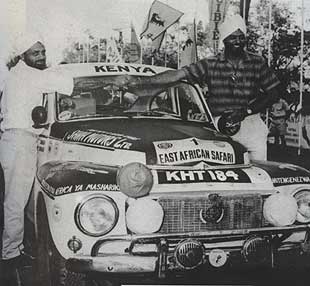

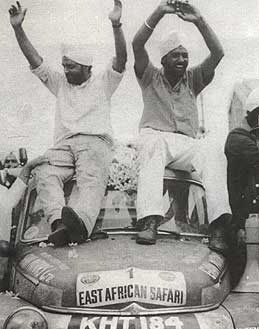

Twice overall winner, in 1963 & 1968, 'Nick' Nowicki being congratulated the 'Sikh' way on his win.

But the 1953 method of classification by

showroom price was retained right up until 1959, with the internationally recognised

categorisation by engine capacity being introduced the following year. A price/performance

index was calculated from 1961, although in recent years this lost much of its

credibility and has since lapsed.

That inaugural year, and in fact for several

years thereafter, no advertising was allowed on the cars as compared with the

present day regulations which emphatically state: "Advertising on competing

cars is specifically encouraged." A colourful form of sponsorship made necessary

to offset the increased cost of the Safari over the years.

Of the eventual

57 starters in that first Coronation Safari-the nomenclature was changed in 1960

to East African Safari and five years later to the present title of East African

Safari Rally-some 28 were trade entries, although probably a considerable percentage

of the so-called "private" entries also had trade backing. The entry

fee was only Sh. 100 per car, which has since escalated to Sh. 1,500 for normal

entries and double that for late inclusions.

Three separate starting points

eventually proved necessary for the first Safari, plans to rail Tanzanian entrants'

cars to Kampala for a single mass start having proved abortive. This "Monte

Carlo" type start to the rally was retained for the next year's event, but

thereafter Nairobi was the start-finish point until 1970.

From 1963, the Governments

of the other independent East African states were reluctant to allow Kenya to

cream-off the considerable benefits that accrued from starting the Safari each

year, and Tanzania in particular made persistent efforts to induce the organisers

to start the rally from Dar es Salaam.

In 1969, matters came to a head, and

the Tanzania Government ruled that the rally would not be allowed to enter Tanzanian

territory. A route taking in only Kenya and Uganda was devised, with Nairobi the

starting point. Next year the Safari start and finish was moved to Kampala.

Meanwhile,

a reconciliation between the organisers and the Tanzanian Government had been

brought about, and although the Safari reverted in 1971 to the traditional Nairobi

start, the following year it was the turn of Dar es Salaam.

It now appears

likely that the starting point of the rally will rotate between the three East

African capitals, although for 1973-the year of the Safari's majority-Nairobi

has again been selected as the start-finish venue. For organisational reasons,

the route does not include Uganda.

42 of the 57 starters in 1953 opted to set

off from Nairobi, with eight chosing Kampala and seven Morogoro. Unlike current

Safari starts, from a ramp at two minute intervals, there was a mass start from

each of the three centres. Conditions throughout were atrociously wet and muddy.

"Typical" Safari weather!

Few competitors had the time or foresight

to carry out a reconnaissance of the route, a now essential feature with the modern

navigator of the genre of Henry Liddon, Chris Bates and Bev Smith compiling copious,

detailed notes of every aspect of the route.

But even in that first Safari

it was obvious that one crew was capitalising on a pre-rally recce and detailed

preparation of their Chevrolet-John Manussis and John Boyes. They motored confidently

to the finish for a Class D win.

Manussis, one of the Safari's great characters,

had to wait until 1961 to register the outright victory he sought for so many

years. Utterly nerveless, he is on record as once telling Lucille Cardwell when

she expressed a wish to get out of his car: "Lucy, if you

jump out now

you will surely be killed. If you stay with me you have a 50-50 chance!"

Incredibly,

Alan Dix-later to become Managing Director of Volkswagen Great Britain-and his

co-driver J.W. Larsen motored their Volkswagen into the Nairobi finish just 17

minutes behind schedule and first of 10 finishers to reach the capital. A further

17 crews to reach Voi 200 miles from Nairobi were also classed as finishers. Volkswagens

won the manufacturers' team prize.

Intrigued by the challenge of this novel

event, there were 50 starters the next year from Nairobi, Dar es Salaam and Kampala,

covering much the same route as in 1953. That had been a road race. The organisers

introduced a compulsory rest stop in 1954 and drastically reduced the required

average speed schedules to 36 mph for Class A and progressively one mile an hour

more for the next three classes.

Not suprisingly, 28 crews (of which three

were later disqualified) finished within the time allowed, half of this number

without incurring a single penalty point. The organisers devised an acceleration/

braking test as a tie breaker. Eventually this took place outside the Nairobi

City Hall following a heavy rain storm, having been moved from the Nairobi show-ground

(now Jamhuri Park).

Ironically, the Vincent brothers who put up the best performance

and two other crews were dis-qualified for exceeding the 30 mph speed limit in

the built-up area of Nairobi. Vie Preston and D.P. Marwaha (Volkswagen), third

in this thoroughly unsatisfactory test, were declared the winners.

Next year's

event was run under FIA rules and a RAC permit. Compulsory rest stops were increased

to four, the distance to 2,510 miles and the number of controls en route to 11.

Penalty points were imposed on final scrutineering of the vehicle at the finish,

as they still are for minor faults today.

Vie Preston and D.P. Marwaha won

the Safari outright, this time in a Ford Zephyr. Their second overall and third

class victory. They were first of 28 finishers from 58 starters, and once again

the ubiquitous Volkswagens won the manufacturers' team award for the third successive

year.

78 cars, the highest number of finishers in any Safari completed the

1956 rally, a dry, dusty affair with the 13 finishers who had "cleaned"

the route without a single penalty point undergoing a track test over one lap

of the Nakuru Park circuit to decide the issue.

This was the second

and last time that an extraneous test had to be used to adjudge the outcome of

the Safari. The Nakuru track test, to a predeter-mined formula, favoured the smaller

cars as did the tight circuit where the long-wheel based cars were handicapped

when cornering.

Eric Cecil and Tony Vickers' lap time in a DKW for 1 min 45-6

sec (the vastly more experienced race driver Jim Heather-Hayes in a Mercedes 220A

was 5-1 sec faster) gave them overall victory, and Simca won the manufacturers'

award, the first French marque to do so.

Run under a FIA permit, the 3,300

mile 1957 Safari was the first to achieve international status. But as in previous

years there was not a single overseas competitor and the rally was still very

much a parochial affair. "Gus" Hofmann and A.A.N. Burton took the premier

spot and spearheaded the Volkswagens to the manufacturers' team prize for the

fourth time. There were 19 finishers, with the rally being held for the first

time (and traditionally since) over the Easter Holiday.

A threatened boycott

by the motor trade before the start, a furore mid-way over the imposition of penalty

points when 45 cars were caught in two speed traps at Tanga and the decimation

of the survivors on the 92-mile stretch from Mbale to Suam River Bridge on the

second leg made this an unhappy Safari for organisers and competitors alike.

The

sealing of vital components had been introduced in 1957, and the next year's provisional

results were not confirmed until November following a protest to the RAC when

the seals on the front suspension of the class-leading Ford Anglia and Ford Zephyr

were found to be broken.

Initially penalised 2,000 and 1,000 points respectively,

this decision was rescinded following an appeal to the Stewards who concluded

that the seals had not been deliberately tampered with. Whereupon, the Mercedes

and Volkswagen entrants lodged a counter protest. A special tribunal re-imposed

the penalties, but the RAC arbitrators ruled the seals were inherently technically

weak and confirmed the Anglia and Zephyr in their class wins.

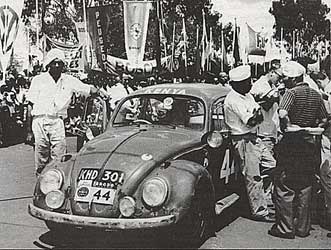

The charisma of the safari is captured in this 1962 photograph of the brothers jaswant & Joginder Singh Bhachu with their Cooper Motor Corporation entered Volkswagen. Joginder is being interviewed by Bikram Singh Bhamra of the Voice of Kenya.

Although

noteworthy for the inclusion of the first-ever overseas entries and the first

all-African crews, 1958 was indubitably a non-vintage year, for although there

were 54 finishers no overall winner was declared for the first and last time in

the history of the Safari: E. M. Temple-Boreham/M. P. Armstrong (Auto Union) won

the Leopard Class with 150 penalty points, an identical score with Lion Class

leaders A.R. and K.M. Kopperud (Zephyr) around whom the great seals protest had

raged. Volkswagen won the manufacturers' team award for the fifth time.

Overseas

interest continued for the 1959 event, won by Jack Ellis with his step-son Bill

Fritschy as co-driver in a Mercedes 219, first of three outright victories for

Mercedes. They repeated this feat the following year for the "double",

Fritschy failed to achieve a unique three-in-a-row in 1961 by just five minutes.

As

it is, no-one has yet won the Safari three times, although Vie Preston/D.P. Marwaha

(1954/55), "Nick" Nowicki/Paddy Cliff (1963*68), Bert Shank-land/Chris

Rothwell (1966/67) and Edgar Herrmann/ Hans Schuller (1970/71) are other crews

to have achieved the double.

Taking no chances on a repeat of the 1958 rumpus

over seals, the organisers in 1959 not only redrafted the regulations but supplemented

the seals with a special yellow, radio-active paint. A Geiger counter reading

taken on application was checked after the rally making the replacement of components

without detection virtually impossible.

Overseas interest in the 1959 rally

was considerable with (as detailed elsewhere) the British motoring Press strongly

represented in Tommy Wisdom, a member of the winning Ford team in 1961, Court-enay

Edwards and Peter Gamier of Autocar. Richard Bensted Smith, later editor of Motor,

drove the following year with Peter Hughes for a class win.

The Safari was

filmed for British television in 1960, and BBC, ITV and Visnews have provided

subsequent coverage. Upward of 100 overseas journalists now cover the event for

newspapers, motoring magazines, radio and television around the world.

The

Ellis/Fritschy combination triumphed again in 1960, one of the wettest Safaris

on record. Wide-spread flooding in Tanzania necessitated changes of route even

before the start. Ford won the manufact-urers' team award for the second successive

year, and included in the winning team were Coupe des Dames winners Lucille Cardwell

and Anne Hall in a Ford Zephyr.

The 1962 Safari ushered in the Pat Moss-Eric

Carlsson era; two of the record 33 overseas drivers competing in the tenth rally

of the series. East African fans took them enthusiastically to their hearts. Pat

Moss came within an ace of an outright win at her first attempt, but Kiambu coffee

farmer Tommy Fjastad and B. Schmider came through for yet another Volkswagen success.

In

1963, the Safari's reputation was further en-hanced when included for the first

time as a qualifying rally in the RAC manufacturers' world rally champion-ship.

It was a year notable, too, for the first Japanese factory entered cars-in the

years ahead to play such a decisive role in the rally.

Freak weather conditions

again tested the elasticity of the Safari organisation to the full, with only

seven of the 84 starters struggling back to the finish. Polish-born, long-time

Kenya resident "Nick" Nowicki and Paddy Cliff were the outright winners

in a Peugeot 404, and were to underscore their mastery of these muddy marathons

when they won the 1968 Safari, again first of seven finishers from a field of

91.

Second were Peter Hughes and Billy Young in a Ford Anglia, a disappointment

they erased from their memories the following year with outright victory in the

1964 rally driving a Ford Cortina GT. Team-wise, that year proved another Ford

benefit, with the Cortina's securing the manufacturers' award.

Brothers

Joginder and Jaswant Singh made Safari history in 1965 when they motored their

second-hand Volvo PV 544 into first place overall, and became the first all-Asian

crew to achieve an international rally success. They had a tremendous welcome

from a huge partisan crowd, having drawn first place and main-taining premier

spot virtually all the way to the finish.

The mass start of the first year

had given way in 1954 to the interval start, with the smaller cars the first away.

The starting order was reversed in 1958 and the next year, and in 1960 the organisers

ex-perimented with an unrestricted ballot for starting positions irrespective

of size or class.

This was varied from 1961 to 1963, when a ballot was held

for starting order in the individual classes with the smaller cars starting first.

The next year this was further changed by the addition of a ballot for starting

order between the classes.

The straight all-in ballot came back into

favour in1965 for two years, but then in 1967 the seeded start (into groups depending

on competition success in the preceding year, experience and competence) was introduced.

This has been retained up-to-date. A ballot is held for order of start within

the groups. The record of the "Flying Sikh" in the Safari is outstanding.

Born in Kericho, Joginder was in 1965 the East African rally champion, winning

outright the Uganda Rally and Tanzania 1000 as well as the Safari. Entered in

every Safari since 1959, he has failed to finish only once, in 1972.

Tanzanians

Bert Shankland and Chris Rothwell in 1966 were the first non-Kenya based crew

ever to win the Safari, taking first position overall in a Peugeot 404. This was

no flash-in-the-pan success, as they demonstrated the following year, giving this

French marque its third win in five years.

But Fords won the manufacturers'

team award both years, and Soderstrom and Palm in a Cortina Lotus made all the

running in the 1967 Safari, looking for the first 2,000 miles as if they would

achieve the history-making feat of being the first overseas crew to win. Luck

was against them.

President Kenyatta flagged away the first cars of the 1968

rally, with Nowicki and Cliff first of the "Unsinkable Seven" to make

it back to the Nairobi finish. As the cars headed north into the night, the rains

broke some six weeks earlier than usual and turned the route into one of the toughest

and most hazardous ever.

The weather had taken an early toll within 150 miles

of the start, with 18 cars enmired on the approaches to the Mau Escarpment in

atrocious conditions. Cars continued to drop out or were time-barred. Only seven

of the 21 cars which started on the southern leg survived. No manufacturers' team

finished.

Conversely, dust was the major hazard of the mile-a-minute 1969 rally.

Jock Aird, a Nakuru farming contractor, and Robin Hillyar won in a Ford 20M after

Soderstrom and Palm had again looked to be heading for that elusive overseas victory

until a broken differential put them out. Bunching was introduced, adding greatly

to the control and spectator appeal of the event.

But an acrimonious dispute

arose at the finish. It was found on scrutineering that the winning car differed

in material particulars (namely that the exhaust valves were three millimetres

larger) from details given in the homologation sheets.

Runners up Joginder

Singh and Bharat Bhardwaj protested to the Safari Stewards who, however, noted

that there was a satisfactory explanation and that a clerical error by Ford of

Cologne was responsible. An appeal to the RAG was contemplated as a challenge

to the validity of the Stewards' decision, but was not proceeded with.

It was

a frustrating Safari for Vic Preston and Bob Gerrish. Eliminated in 1968 by their

failure to obtain the relevant stamp at a control, they were within 600 miles

of the finish in the 1969 event when outright victory slipped from their grasp

yet again. Twice, in 1966 and 1967, this formidable duo had been second overall.

Atrocious

conditions characterised the 1970 rally, with speeds of more than 100 mph called

for on some sections. For the first time, the Safari started and finished outside

Kenya, at Kampala.

For Malindi hotelier Edgar Herrmann eight years of endeavour

were rewarded when he took first place overall driving a Datsun 1600SSS with Hans

Schuller after what the East African Standard called "an immaculate drive

which must rank as one of the greatest in Safari history."

However, the

rally was marred by the unfortunate death of a former Ugandan Army captain David

Ndahura who was driving with Ismail Sebbi. He was swept away and drowned when

his Peugeot 404 was marooned on the flooded Tiva Bridge near Kitui in the Kenya

section of the rally.

But fatalities in the Safari, despite the speed and ruggedness

of the country through which it is run, have proved gratifyingly few. The first

occured in 1957 when Somakraj and Charlie Safi failed to negotiate a corner leading

up to the Ruvu River bridge in Tanzania and plunged into the flooded river and

drowned.

In 1971, Nairobi University lecturer Cyrus Kamundia of Nyeri was killed

while on a pre-Safari recce with co-driver G. Gichuru in Tanzania, and the preceding

year a Japanese service crewman died in a crash before the Safari. The tragic

exceptions to an unusually fatality-free rally.

Safety belts were made compulsory

in 1962, and the roll bar in more recent years. Both have con-tributed to preventing

serious injury on many occasions, as has the strength of the modern all-steel

body. For "prangs" in the Safari have been numerous.

A record entry

of 118 cars made 1971 another milestone in the history of the Safari, which covered

an all-time high of 6,400 km. Overseas and African entries were also the highest

on record. Again it was Herrmann and Schuller, this time paired in the potent

Datsun 240Z, who gained outright victory.

Bjorn Waldegaard and Sobieslaw Zasada

were ahead of the field as the cars headed into Uganda, and with three-quarters

of the rally run, Waldegaard had a 23 minute lead and looked set to break the

jinx on overseas drivers.

But he crashed his Porsche trying to overtake his

team-mate Zasada, who was only 200 miles from the finish when his Porsche developed

intermittent engine trouble which the Stuttgart mechanics were unable to correct

and he gradually dropped back through the field for eventual fifth place overall.

So

near yet so far. . . the inevitable overseas victory which had eluded allcomers

for so long was eventually achieved in 1972. Hannu Mikkola and Gunnar Palm raced

their Ford Escort RS1600 into the Dar es Salaam finish for an historic overall

win and another manufacturers' team prize for the British marque.

For the first

time the Safari started and finished in the Tanzanian capital, the first cars

being nagged away by President Julius Nyerere. 18 of the 83 starters finished,

with Anne Taieth and Sylvia King Coupe des Dames winners in a Datsun 1600-the

first all-women crew to complete the Safari since 1968.

The Safari stands alone

as the sole international example of its kind, the most difficult rally in the

world. An almost parochial affair at the start, it has matured over two decades

into one of the great motoring events on the world calendar. Truly, the Safari

has come of age.

Some

impromptu cooling for this Zephyr at a checkpoint.

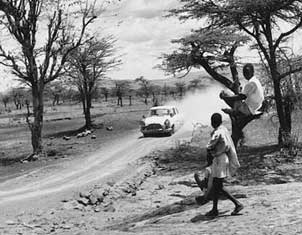

African spectators enjoying the Safari.

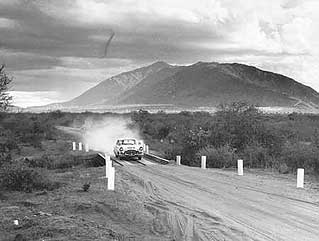

A Safari Zephyr throwing dust in a picturesque atmosphere.

A Mitsubishi Lancer crossing a river.

THE FLYING SIKH - 'SIMBA YA KENYA'

JOGINDER SINGH

If anyone in East Africa achieved

the status of a national hero through motor rallying, it was undoubtedly Joginder

Singh. He was not only the first Asian driver ever to win an international rally

but also the first man to win the Safari three times. His tally of 19 finishes

in 22 Safari starts is unique: a record of consistency in 'the world's toughest

rally' that will probably never be beaten.

Sardar Joginder Singh Bhachu was

born on 9th February 1932 at Kericho in Kenyan in the western highlands. His father

Sardar Battan Singh came to Kenya in the 1920's from Village Kandola Kalan, near

NurMahal in the district of Jullundur, Punjab. His mother's name was Sardarni

Swaran Kaur. Joginder Singh was the eldest of eight sons and two sisters and was

educated at a boarding school at Nairobi. But engineering was already in his blood

as he was able to drive an old 1930s Chevrolet by the time he was 13.

He worked

as a spanner boy in his father's garage and later moved onto work with larger

motor companies and in 1958 became the first patrolman for the Royal East African

Automobile Association armed with a fearsome 650cc BSA motorcycle and sidecar.

Upto the age of 26 he had no experience of motor sport. His father was a fast

car driver, perhaps some of that had rubbed off on his son but it was probably

Joginder Singh's mechanical sympathy and meticulous car preparation that were

to have the biggest influence on his future rally career.

HIGHLIGHTS OF RALLEY

ACHIEVEMENTS OF S JOGINDER SINGH BHACHU East African Rally Champion:

1965 1970

& 1975 Kenyan Rally Champion:

1966 1967 1969 1970 & 1975

Motor Sportsman

of Year:

1970 & 1976

Won over 60 East African Championship

Rallies

in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania.

Southern Cross Australia:

5th (1970) 4th

(1973) 2nd (1974)

overall in Mitubishi

Acropolis Rally Greece:

9th (1966)

overall in Volvo

We present some photos of bygone era of Joginder and his exploits

The

SIMBA of Kenya being confronted by the SIMBA of the jungle

The

SIMBA of Kenya being confronted by the SIMBA of the jungle

The

13th Safari certainly wasn't unlicky for the Sikh brothers Joginder & Jaswant.

They won the event in a second hand Vplvo PV544 that already had many thousands

of miles on the clock. The first ever international rally success by a non-European

crew. (The 13th safari had car no. 184 (total 13) PV544 (total 13) - Unlucky for

some BUT LUCKY for the Bhachu brothers)

Here is what one

paper wrote of the incredible victory:

VOLVO PV544

The

PV went from strength to strength, winning our own RAC rally, in probably the

fastest Volvo driver Tom Trana's hands in 1963 and 1964. It was a bit outdated,

as a rally car by then but in the correct hands was still a winner on rough, tough,

loose surface events. The best PV story of all I think is of Joginder and his

brother Jaswant Singh's 1965 East Coronation Safari win. Volvo had taken four

cars to Kenya in 1964 for tracks. It was accepted as the hardest event in the

calendar. The cars arrived too late that year and could not be tested under African

conditions and for a variety of reasons they all failed to finish. Volvo did not

take all the cars back to Sweden with them but left one for Joginder Singh to

rally in Africa for the rest of the year. During this time he modified the PV

and strengthened it where necessary and lowered the axle ratio. The car had covered

42,000 miles mostly under rally conditions. Joginder's intention was to enter

the 1965 Safari Rally. The story has a fairy tale ending, they won by 100 minutes.

You can perhaps imagine the headlines in the papers -

"Safari won in a second hand car." Joginder won again, but

not in a Volvo, in 1974 and 1976 just to show that the driver had a fair bit to

do with the result. Any of you lucky enough to attend a PV Register meeting a

few years ago at the Shuttle worth Trust in Bedfordshire would have been able

to see Joginder and his beloved PV (KHT 184) now immaculate in its original white

paint.

I just wonder if any of the old works cars are still in existence and

just what modifications the factory used in those no holds barred Group 6 events

like the Alpine and Liege. The 1961 Homologation papers show four wheel disc brakes

as well as the Joginder Singh inspired four damper front suspension set up. Did

they ever use two twin choke Weber or Solex carburetors as offered by the Volvo

R Sport in any events? It would not surprise me and I would love to know. I list

below the production records and model changes - these taken and other material

from Andrew Whyte s book the "Volvo 1800 and Family."

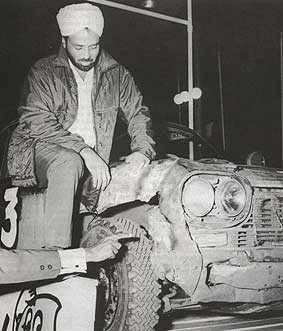

The

joy of winning

Joginder

& Smith were among the 'Unsinkable Seven' in 1968 and brought this Datsun

H130 back to the finish for fifth place overall.

The

Volvo of Joginder being agmired by the enthusiatic crowd in Nairobi

The

Volvo of Joginder being agmired by the enthusiatic crowd in Nairobi

Joginder in a VW in 1960 safari driving through a river? or road?

In a new Mitsubishi Colt Joginder jumps a bridge iand eventually won this event

Prince Edward flagging off the 50th Safari Rally in Nairobi . Veteran driver Joginder Singh can be seen on extreme right.