Great

Indian Olympians

THE STAR

EXTRAORDINAIRE

BALBIR

SINGH

It

was time for India's tryst with destiny. In 1947, the nation was in turmoil. Freedom

from 200 years of British rule did not come without its share of trauma and tragedy.

The country was partitioned on religious lines and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan

was created in the northern and eastern parts of the coun-try. A large-scale migration

of population took place from across the new border. The partition was a painful

affair, solemnised amidst unprecedented violence, mayhem and distrust. Every hockey

player of that era had his own tale of woe to narrate.

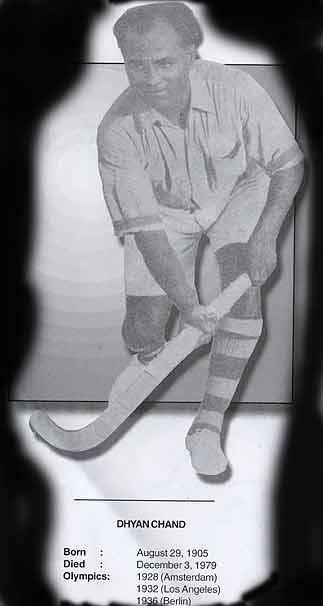

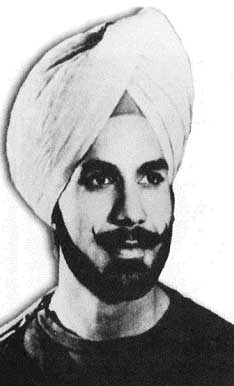

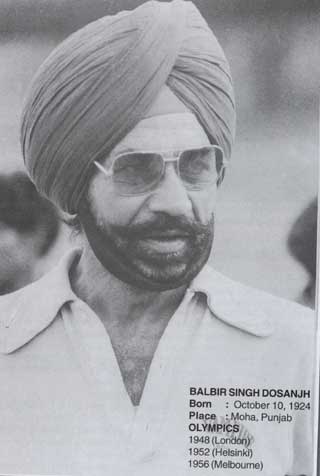

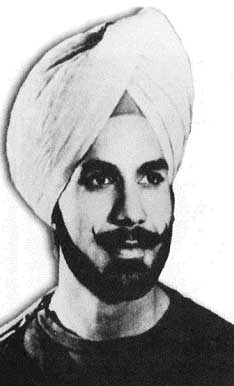

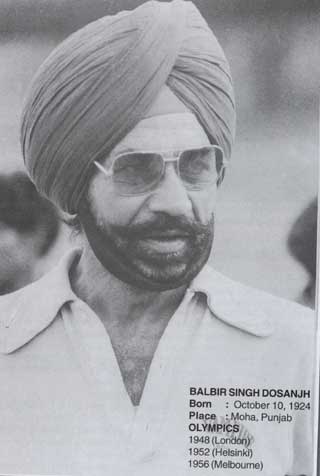

Balbir

in his mid 20s.

Lahore, the nerve centre

of the sub-continent's hockey, the city that gave seven of the 18-member Indian

team for the Berlin Olympics, had become a part of Pakistan. Many hockey giants

living in Lahore had to migrate to India and vice-versa. Many players of the game

from Central India choose to settle in Pakistan. That included Y.M. Yousuf, who

later became an Afghan citizen. The question that naturally arose was whether

India would be able to maintain its suzerainty without these great players.

Another

related development pertains to the Anglo-Indians. Though they comprised a minus-cule

of the population in a country of about 350 million, they constituted the very

core of Indian hockey in the pre-World War era. Nine out of sixteen stars of India's

first Olympic team to Amsterdam in 1928, belonged to this community. With the

new political developments, a substantial chunk of them had an opportunity to

seek greener pastures. They left India in droves and settled in England, Australia,

Canada, New Zealand and elsewhere. Great lovers and practitioners of the game

that they were, the magnitude of loss to Indian hockey was enormous.

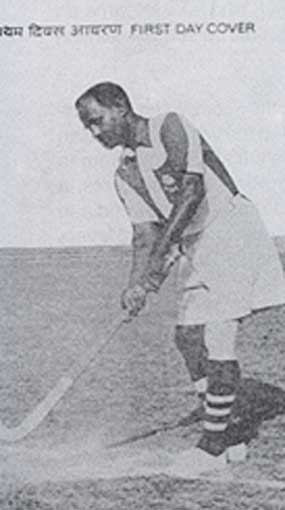

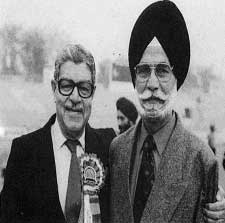

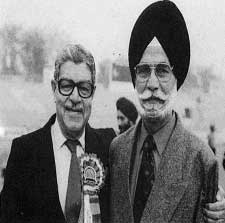

Balbir

Singh with Keshav Dutt

It was under the backdrop

of such depletion of talent and a scenario in which the wounds of partition were

far from erased from the collective consciousness of the country, that India started

its campaign in the 1948 London Olympics. There was enormous pressure to keep

the country's image intact, an image so painstakingly acquired amidst a cesspool

of adversities in the 20s and maintained right until then. Further the powerful

British team, who till then refrained from playing Olympics hockey, was back in

the fray. The challenge India faced was formidable.

It is under

this historical backdrop that Balbir Singh played an outstanding role in lifting

India to lofty heights. Not many would have expected the 24-year old centre-forward

to inherit the legacy of Dhyan Chand at the London Olympics so easily and elegantly.

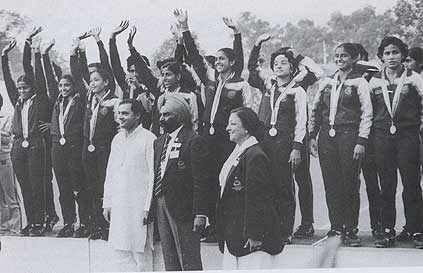

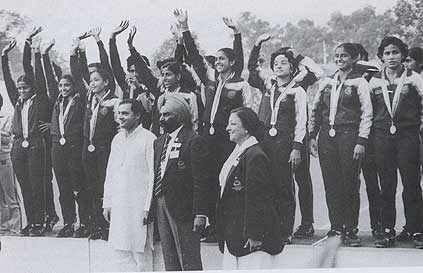

Balbir

Singh with G.S. Bodhi, coach, 1975 World Cup that India won.

The

early trapping of the man who was to decide the outcome of two more Olympics was

evident in the first match he played at London. Although he was not in the first

eleven of the opening game against Argen-tina, when a player named Regie fell

ill this Punjab player was fielded in a match against Argentina. The newcomer

turned the match single-handed! Ripping apart the defence, he scored six goals

and steamrolled the Latin Americans to a 9-1 defeat. Thus, he achieved a rare

feat of scoring a goal on debut, and making a hat- trick. For a man who later

at-tained a hat-trick of Olympic golds, the goal spree proved to be the harbinger

of things to come. However, he had to wade through many uncertain phases before

carving a niche for himself in the world-class hockey.

The first chance to

establish his power over the game and prove himself came in the next match itself.

He was asked to get ready for an encounter against Spain. But just when he was

entering the ground, he was asked to stay back and the manager Pankaj Gupta replaced

him with Nandy Singh. Like his role model Dhyan Chand who used to look over every

humili-ation inflicted on him in the interest of sports, he did not utter a single

word against the decision that robbed him of a chance to prove his calibre. The

same fate befell him during the semi-final against Holland. He was among the first

eleven and had also entered the ground. But just as he was about to bully-off,

captain Kishan Lal asked him to make way for Glacken. What made the managers P.C.

Chatterjee and Pankaj Gupta to force the captain to replace Balbir Singh, that

too much against his will, is still a mystery.

Yet, perfect gentleman as he

was, Balbir Singh walked back to the dressing room quietly. When he was again

put among the first eleven for the final, he nurtured doubts about him being allowed

to play. But thankfully nothing of the sort occurred in the next match. Grabbing

the opportunity with both hands, he proved his superior talent by responding in

the only way a champion sportsman would. He let his stick do the talking. Latching

on to passes from captain Kishan Lal and inside-forward Kanwar Digvijay Singh

'Babu', he pumped both the goals India scored before half-time. This paved the

way for what can be described as a historic Indian victory over the masters, with

four goals scored in its favour while conceding none.

Hockey is a team game

yet so skilful were players like him that they made it seem like a one-man show.

Such were his skills and predominance that India managed only single-goal-margin

victories in the matches in which he had not played. Independent India's first

Olympic gold settled all pre-tournament speculations at rest. Partition or no,

talent drain or no, India was as invincible as ever. The victory gave India an

identity, a pride and a springboard for many more victories to follow.

Balbir

Singh received immense praise but none of it would affect him or make him vain.

Instead, it motivated him to scale lofty heights. The chance to do so came during

the next Olympics. At Helsinki in 1952, glory beckoned Balbir Singh. His continued

his goal-spree in the National Championships, leading India to an all-win visit

to Afghanistan truly put him on the spotlight. Unlike the London edition, not

much socio-political significance could be attached to India's campaign for Helsinki

as it had already proved its potential in 1948. Yet, prestige was at stake and

India had to defend the title. For a country that had no prospects in any other

discipline, hockey alone had to meet the aspirations of the millions of its sports

lovers. A heavy responsibility to shoulder indeed.

A strange format posed a

problem of a different kind for the leading teams at Helsinki. India, like the

other three semi-finalists, was directly seeded in the quarterfinal. That meant

that they were given a chance to play only three matches, all knockout punches,

all precarious with no time left for recovery or remedy. Hence, enormous pressure

was on the forwards to score goals to avoid stumbling at any stage.

As the

flag-bearer of the Indian contingent at the opening ceremony, Balbir Singh knew

this.

He was cut for such a role, but he was also worked up as some cynics

doubted his form,

since his team had lost both the All India Police Games and

the National Championship that year. The first match against Austria, which India

won laboriously at 4-0, did not give any indication of things to come. He could

send the ball home only once. A heavy dose of

dressing down by the team management

seemed to have pumped ounces of adrenaline in him as was evident from his subsequent

performances.

In the semi-final against the masters Great Britain, Balbir Singh

came on his own. All three goals India scored came from his ex-traordinary ball

sense, artis-tic but limited dribble and first-touch scoring shots. A second hat-trick

in only his fourth Olympic cap and five goals against two-time goldmedallist Britain

in only two matches proved the stuff of which the champion was made.

This alerted

the finalist Holland. Always a defence exponent, they put two defenders to contain

the marauding Balbir Singh. Incensed Balbir Singh replied in style. He made mincemeat

of the de-fence, with excellent support from wingers Rajagopal and Raghubir Lal.

He alone scored five goals. Riding on his form, India romped home to a memorable

6-1 victory, India's fifth straight Olympic gold. This included a hat trick, and

a victory in three of the five matches played - a record which remains unbroken

till date.

It is his expertise inside the circle that had many comparing him

with the legendary Dhyan Chand. "Ball with Balbir Singh in the circle, and

the defence is paralysed," exclaimed his peer Keshav Dutt. Never would Punjab

Hockey Association field a team without him. Hardly would he get any respite from

matches. Come what may - occasional fitness hassles, bouts of fever or domestic

compulsions, Balbir Singh had to be a part of the team. Officials would visit

his house and force him to play. He obliged them every time and that too with

nearly fantastic results.

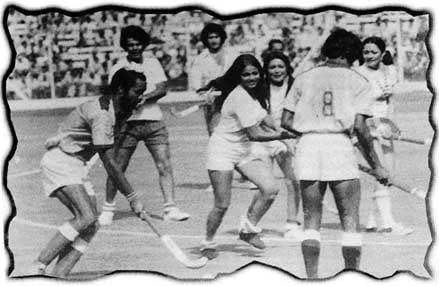

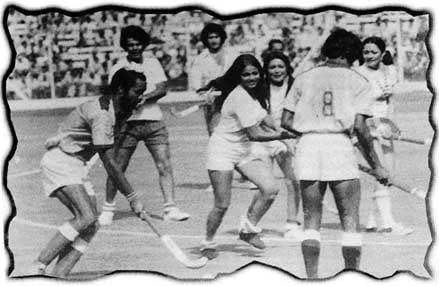

The

victorious Indian world cup team (1975) in fun hockey with film stars.

In

the Xllth Olympiad at Melbourne, Balbir Singh fractured his hand. After scoring

five goals against Afghanistan in the opening match, a rasping drive from the

right back hit his fingers when he boldly tried to intercept it. He was ruled

out of other matches. This rattled the Indian management. Balbir Singh himself

rued his fate. If it was some mischief in 1948 that left him out for two matches,

eight years later it was bad luck that kept him from playing in all the matches.

He remained a mere spectator in the matches against United States of America and

Singapore. Meanwhile, his injury was kept a closely-guarded secret. He was asked

to keep his injured hand always covered. This also had a reason. He was the main

scorer in those days. In fact, only two years earlier, during a tour to Malaysia,

he had gathered as many as 83 of the 121 goals scored in 16 matches; a year later

in the New Zealand-Australia tour, his bag was full with 141 of the team's 203

goals in 38 matches. Hence, the opposition had made it a part of their strategy

to depute two defenders to contain him. If the news of his injury would have spread,

the opponents would have gained much more confidence than they did with Udham

Singh occupying the top scorer's spot. Such was his stature that even when injured,

he had a significant role to play - of imparting a psychological boost to his

team.

What was expected did happen in the semi-final against Germany. Balbir

Singh, bolstered by doses of painkillers, attracted two defenders. As a result

Udham got a lot of free space to push his goals through. Subsequently, it was

his lone goal that made India the winner. In the final too, the Pakistanis - it

was the first ever meet between the two gifted neighbours - had two defenders

hounding on him which eased the pressure on other forwards. One shudders to imagine

the fate of rival teams had Balbir Singh been fit to score. But it was not to

be. In this match a penalty corner conversion by Randhir Singh Gentle led India

to its sixth straight gold. Balbir Singh recollected later, "For me, on one

hand was the agony of pain, on the other the ecstasy of winning glory, of triumph.

The latter outweighed my pain. It now mattered little even if I lost both my limbs."

His

post-Olympic career too was colourful. He changed his employment from Punjab Police

to accept the leadership of the Sports Department of the Punjab government. He

innovated and implemented many realistic schemes that laid the foundation for

the state to emerge as the strongest sporting province of India. Many brief stints

as national coach, selector and manager marked this spell. Worthy of mention is

that under his managerial capacity, India won its only world Cup title in 1975.

After this success, the elated Balbir Singh penned his autobiography The Golden

Hat trick: My Hockey Days. When the Government of India instituted the first civilian

award, 'Padamshree' in 1957, he deservedly was the first one to receive it. Balbir

Singh now lives with his son in Canada.

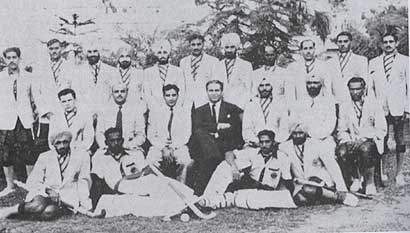

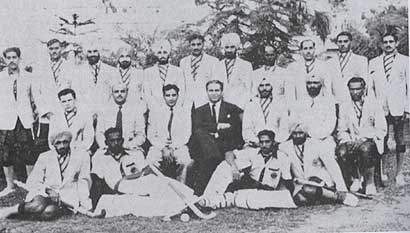

Victorious

1956 Olympic Hockey Team

HOCKEY

KINGS

BALKRISHAN

SINGH - COACH TO THE CORE

Some

unique aspects distinguish the life and career of Balkrishan Singh from that of

the five hockey legends portrayed so far. Unlike these luminaries, who continued

to be on the payrolls of their employers after they had hung their boots, Balkrishan

chose to serve the game in a different but professional and purposeful way even

as many years of hockey were left in him. The times they lived in and played the

game were different and the demands of their lives were not common. Yet, comparisons

between them yield interesting insights into the lives of these personalities.

Dhyanchand

became the first chief coach of the National Institute of Sports (NIS), Patiala,

India, only after his retirement from the Indian Army; After three Olympics, Balbir

Singh discharged his service in Punjab Police before shifting to another department

in the same State; Leslie Claudius too continued in Customs long after he had

retired from professional hockey; the career graph of Shankar Laxman too was no

different; Md. Shahid continues working in the Indian Railways. No doubt all these

players dabbled in spells of national duty as selector, manager and even coach,

but for them the mainstay remained their service, which was not always related

to hockey. The career graph of Balkrishan was, however, different in so far as

he resigned from the Indian Railways even as he was in peak form and preferred

to join NIS as 2 coach where he served for three decades. That gave the distinguishing

aura to his highly successful career as a hockey player.

From a historical

perspective, this continuity placed him in the unique position of being a player

who had been in touch with all the five legends outlined in this book - Dhyan

Chand was his mentor in NIS for six years; he played alongside Claudius, Laxman

and Balbir Singh; and he coached Shahid for two of the three Olympics played by

him. Therefore, in studying his career one can traverse through the vicissitude

of Independent India's hockey history.

It is true that unlike the other five

hockey personalities, each of whom had figured in three Olympics, he played Olympics

only twice - in 1956 and 1960. But he compensated this in more than one way by

becoming the only one from the elite group to coach Indian teams for four Olympics.

Even Dhyan Chand did not coach any Olympic team.

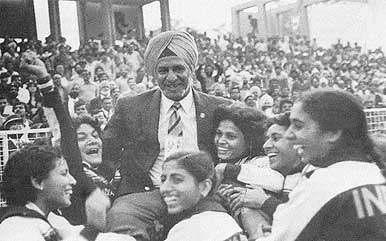

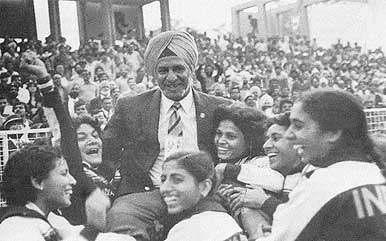

Indian

Girls won their maiden Asian games Gold in 1982 when Balkrishan was the coach

AND he gets the toast for that feat (below)

Balkrishan

was born in March 1933. His career could not but have been such an illustrious

one as he was born in a sport-loving family and grew up in a sports-conscious

city, Patiala. His father, Brigadier Dalip Singh, in the true traditions of the

Indian Army, excelled in sports and was one of the greatest track and field athletes

of his times. He participated in the 1924 Paris Olympics even before Indian hockey

entered this global arena. He was seen in action in the next Olympics too - a

remarkable achievement for someone who did not face the rigours of coaching as

it existed in many other countries during the period. He secured eighth position

with a jump of 21 feet 2 inches.

Balkrishan's schooling was accomplished at

his hometown Patiala after which he joined the famous F.C College, Lahore, for

graduation. His father being an alumnus of the great institution put him in the

right track when he advised his young son, "I command respect in the college

through sports. You must keep my name by way of excelling in sports". He

took the words to his heart and like his father became a grand double Olympian,

albeit in a different sport, but not before proving his expertise in athletics.

When

he was still under 16, he broke the Punjab University record in hop, stop and

jump in 1949, and became the inter-university champion in 1950. He also broke

the University high-jump record. At the same time, he represented the university

in hockey from 1950 to 1954. In 1954, he got the first call to join the national

team. He obtained the country's colours in the International Hockey Festival at

Warsaw, Poland. Around the same time, he joined the top-notch Indian Railways.

That gave him enormous scope to take part and prove his worth through various

tournaments.

Even amidst tough competition against such established

defenders of fame as Shanta Ram, Murthy and Swaroop Singh, young Balkrishan could

secure a berth for himself in the 1956 Olympics team. His sparkling play in the

Aga Khan Cup a year earlier paved the way for Olympic entry. At Melbourne, he

played all matches except the final, giving way to Bakshish Singh. The sight of

the tall, robust player who was a picture of confidence evoked awe in the rival

forwards in all the matches he played. So enamoured were the Australians by his

majes-tic and flawless tactics that he almost emerged a cult figure in later years.

Two

years later, in the third Asian Games, his game was in full flow. By then he had

led the Railways to the victor's podium twice, in 1957 and 1958, beating formidable

Bombay in its own backyards on both occasions. His ambition of playing against

Pakistan, which eluded India at Melbourne, was fulfilled here. He played the best

match of his life against Pakistan. He and Bakshish Singh foiled every free-flowing

attack of Pakistan forwards in the final. The match ended in a goal-less draw

though Pakistan was declared winner on the basis of goal average.

With one

more victory for his captaincy in the National Championship, this time over Services

at Hyderabad, he became an automatic choice for the 1960 Rome Olympics. Here again,

Pakistan became the champion. The two defeats shook the soul of young Balkrishan,

rever-berations of which he could feel even after 40 years had rolled by. For

India this was a time of introspection. A manifestation of this was the emerging

awareness for scientific training and the setting up of NIS. Along with hockey

stars of the day, Dharem Singh, Charanjit Singh and Charles Stephen, Balkrishan

underwent one-year training in coaching in the NIS. Inspired by the personality

of the chief coach Dhyan Chand, the first-batch incumbent topped the course with

93 percent marks.

He returned to Railways and led his institution to another

title at Hyderabad, beating the defending champion, Services. Then came the call

of his life, an offer to join the NIS faculty. It was a full-time job. He had

to decide between competitive hockey and the new offer. He preferred the latter.

The momentous decision was taken in a split second as he had by then developed

a liking for strategy, tactics and all the mind-games that goes along with coaching.

With that his seven-year affliction with international hockey came to end. Another

glorious chapter that would endure for 31 years had commenced.

With Dhyan Chand

at the helm, sky was the only limit for this inquisitive youngster to enlarge

the horizons of his hockey knowledge. So impressed was Dhyan Chand by his abilities

that, a year before he retired he wrote in his confidential report, "I have

full faith in Balkrishan's ability. He is the finest young coach in the country

today." That was more than adequate foi the authorities to elevate him to

the post that Dhyan Chand adored till then. In the same year 1967, the Australian

government extended an invitation to him to offer expert counselling ir the country.

He gladly accepted the challenge and spent four and half months in Australia During

his stay, he visited every provincial capital for about a fortnight, and imparted

all the knowledge he had to schoolboys and girls as also to aspiring trainers.

He truly acted as the ambassador of India during that tour held under the aegis

of a cultural exchange programme

The trip was sponsored by Rothmans Sports

Foundation and he was paid a honorarium of US$ 400 per week, besides all other

expenses paid - a huge sum for a coach in amateur sports. More than the financial

aspect, what gladdened the heart of the 34-year old Balkrishai was when the then

Prime Minister of Australia, Mr. Malcolm Fraser, himself an hockey enthusiast

and umpire, chose to praise him. In his subsequent visit to India, he thanked

his counterpart Morarji Desai, in an official banquet, for sparing the services

of experts like Balkrishan to improve hockey in the country. Balkrishan also took

an All India Universities team to Australia in 1971. The team included such stars

as Surjit Singh, Baldev Singh, Ajit Singh,HJS Chimni, P.E.Kalaiah and V.Baskaran.

During this visit the team played eight matches with different Australian teams.

They won all the matches, scoring 65 goals and conceding just six. The year 1977

saw him visiting the same country once more.

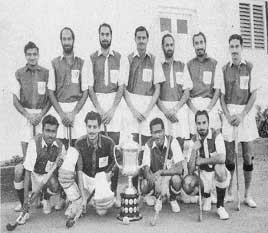

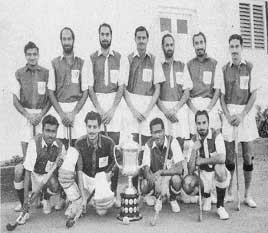

Balkrishan

Singh (second left) as a part of Northern Railways team that won the inter-railways

championship.

This Adelaide tour was sponsored

by a Federation Government grant and his coaching spells in schoolswas supported

by Savings Bank of S.A. and Coca-Cola. In all these tours, there was nodenying

the impact of his charisma - a blend of style, intellect and a forcible personality.

It

was due to the services rendered by experts like Balkrishan that the bond between

the two countries grew from strength to strength. India was regularly invited

for the Esanda tourna-ments held in Australia in the 80s and for the double-leg

4-Nations in the 90s. Women teams under Richard Charlesworth also visited India

many times.

His frequent visits to this continent and other parts of the world

enriched his domain of knowl-edge on a global scale. He wrote about Australia's

Charlesworth, a legendary hero in 80s, "Not many would be aware of the fact

that in all the leading competitions in which Charlesworth played as an inside

right, the Aussies lost. My conviction is that had he played as an inside left

in the Fifth World Cup (Bombay), Australia may well have won the trophy. Similarly,

in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics and in the third PIA Champions Trophy at Karachi,

Australia could have performed better if he was in the inside left saddle. I do

not know if Aggis (the Aussie coach) will acquiesce with me or not, but the 'hockey

doctor' hopefully will agree to my assessment." In the sixth World Cup staged

at London, Charlesworth switched over to inside left position and Australia won

the World Cup trophy!

India too availed of his services. Even as he was under

35, he coached the 1968 Mexico Olympic team where India won a bronze medal but

it did not enthuse anybody, as the country was the defending champion then. Balkrishan

could not stop wondering why in this tourna-ment all the five goals that the great

Prithipal Singh scored against New Zealand through penalty corners were disallowed.

Incidents

of such nature, cataclysmic changes in the rules of the game, their haphazard

interpretation by umpires and the frequency with which they were changed by the

interna-tional governing body, Federation de Internationale Hockey was scrupulously

studied by Balkrishan. Once he wrote, "One of my students doing his master's

course in hockey wrote a thesis on penalty corner and by the time he completed

the job, the rule was changed, rendering his valuable work invalid." He wondered

when games like football, which has captured the imagination of people all over

the world has made only one change in rule in forty years, why were so many changes

brought about in this game. Based on analytical studies and research, he proposed

abolition of penalty corners and striking circle in order to make the game simple.

Not many agreed with him, but it exemplified his authority on the subject.

It

does not mean that he was dogmatic and against any change in rules. He welcomed

the abolition of penalty bully and introduction of artificial playing surfaces.

He was the first Indian coach to adopt the 4-4-2-1 style of field formation, which,

according to him, was more suitable for synthetic grounds. His brainchild 'total

hockey', which was often criticised by the purists for its defensive aspects,

has become the guiding paradigm of present-day coaches. The way he metamorphosed

the unique Indian traits in the concept of total hockey earned him many laurels

in the 80s and proved his caliber, dynamism and readiness to adapt to the changing

scenario. Being a strong protagonist of individual style and brilliance, without

which Indian hockey would not have attained the type of fame it did, he could

bring out the best in the likes of Md. Shahid, Merwyn Fernandes and others. He

once said, "Holland without Floris Bovelander and Pakistan without Shahbaz

Ahmed would mean an army without a general." He believed that Individual

efforts are conscious practices and are far ahead of mechanical practices which

coaches dole out during coaching sessions.

The synergy between tactical

acumen and individual talent that he so effectively in-grained in the concept

of 'total hockey' proved fruitful for India in many of its pres-tigious campaigns.

The significant role he played in developing Indian hockey can best be understood

on studying the cir-cumstances under which he was invited to train various Indian

teams. Every time he was invited for national coaching, those were invariably

distrust calls.

India's challenge in the 1980 Moscow Olympics was entrusted

to him after the country faced two lows - the first in the preceding 1976 Olympics

in which, for the first time, India had failed to win any medal, slipping to a

record low in ranking at seventh. The second was in the 1978 World Cup in which,

despite being the defending champion, India could not move beyond the fifth rank.

Balkrishan developed a young team that won the gold at Moscow. But he was not

sought in theWorld Cup that followed in a year and was recalled for the next Olympics

only after India fared poorly in the Bombay World Cup and in the Delhi Asian Games.

He used the spell to put together a girls' team in the Asian Games and they won

the title on their maiden entry. Till today, even after five editions, that remains

the only Asian gold for the Indian girls' team.

As

coach of the Asian XI Balkrishan receives the Pakistanis' warmth

In

the short span of a year, the men's team that he had so painstakingly developed

made it to the semi-finals at the Los Angeles Ol-ympics till a new system of considering

the

goal aggregate to decide pool rankings led India down. India ended the

campaign at fifth rank (beating Holland 5-2 in the last match). Yet he was axed.

His turn came in 1991 as India dished out another dismal fare, this time at the

Lahore World Cup.

In the run up to the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, his team set

up a tremendous record. It won all matches in annexing the title of the Sultan

Azlan Cup (1991) at Kuala Lumpur. That set the stage for sponsors to pour in.

In the Europe tour that followed, the team had a sponsor in Chhatisgarh Distillers

who awarded hefty sums for the 'Man of the Match' of all 15 tests India played.

12 wins and two draws out of the 15 matches in that tour created a great expectation,

but the players' greed and indiscipline spoilt the whole show at Barcelona - a

sad end to an illustrious career. But his efforts in giving India a meaningful

coaching perspective cannot be denied.

Had he ever been given a four-year tenure,

the history of Indian hockey would not have been as discouraging as it was in

the 70s and 80s. In the 1972 World Cup his team did not lose a single match, and

lost the title only due to the penalty shoot-out. Yet a new coach was found for

the 1975 World Cup. Why was he not in the scene even after the Moscow Olympics

gold is another question that would never be answered to satisfaction. If a master

theoretician in the mould of Balkrishan was not hailed at par with contemporary

greats such as Horst Wein, Paul Lissek, David Whitekar, Roelent Oltmans, Richard

Aggis, the fault lies with the system in which he had to work and not on the want

of anything in his persona.

Balkrishan coached various Indian teams within

a period of about a decade in six different spells. Never was a single assignment

allowed to last for more than two years. Yet, he did not lack behind in putting

all possible effort in imparting the best training. During the period India won

29 matches, drew nine and lost seven in the Olympics, World Cup, Champions Trophy

and the Asian Games. That four of the seven losses came in the Barcelona Olympics

alone is the only dark patch in an otherwise consistent career. That his teams

faced defeat against Pakistan only twice in 14 meetings further glorifies his

coaching prowess. His commentaries in the book 'World Hockey'are reflections of

his scholarly erudition of the game. He also had gift of the gab. His off-the-cuff

remark, "umpires are like watches, they never match" is an oft-quoted

phrase.

The above articles have

been taken with thanks from 'The Great Indian Olympians' by Gulu Ezekial &

K.Arumugam.

MENU